Olive Ridley Turtle |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Cheloniidae | Lepidochelys olivacea

English common names: Olive Ridley Turtle, Olive Ridley Sea Turtle.

Spanish common names: Golfina, tortuga golfina, tortuga lora, tortuga olivácea.

Recognition: ♂♂ 72.3 mmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 79 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace.. Lepidochelys olivacea is unique among sea turtles found in Ecuador because it has 6–9 pairs of costal shields. Although adult males and females of this species have a similar body size, males are distinguished by their longer, thicker tails and larger front flipper claws, which they use to grasp females during copulation.

Picture: Adult female. Parque Nacional Machalilla. Manabí, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male. Parque Nacional Machalilla. Manabí, Ecuador. | |

| |

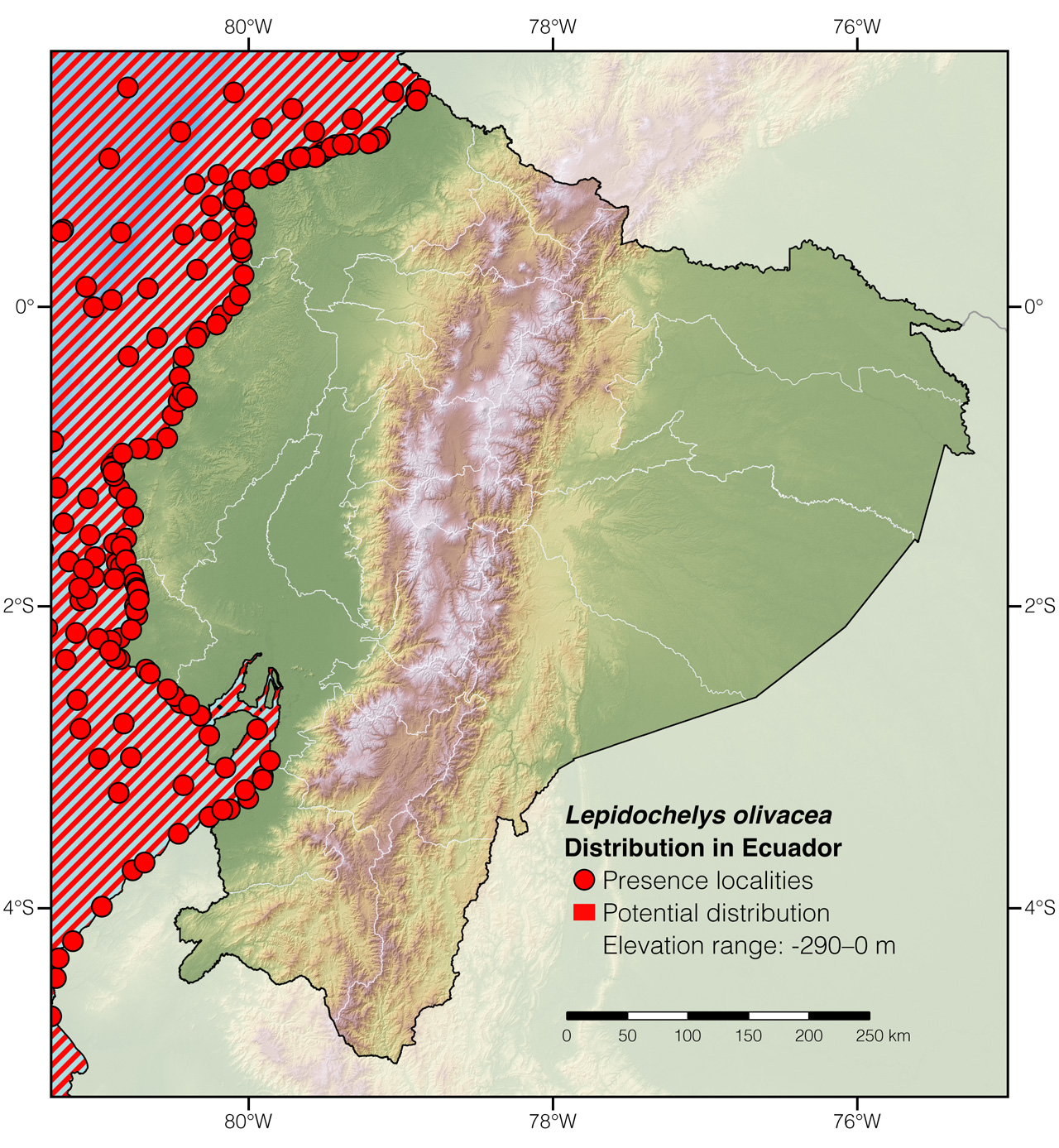

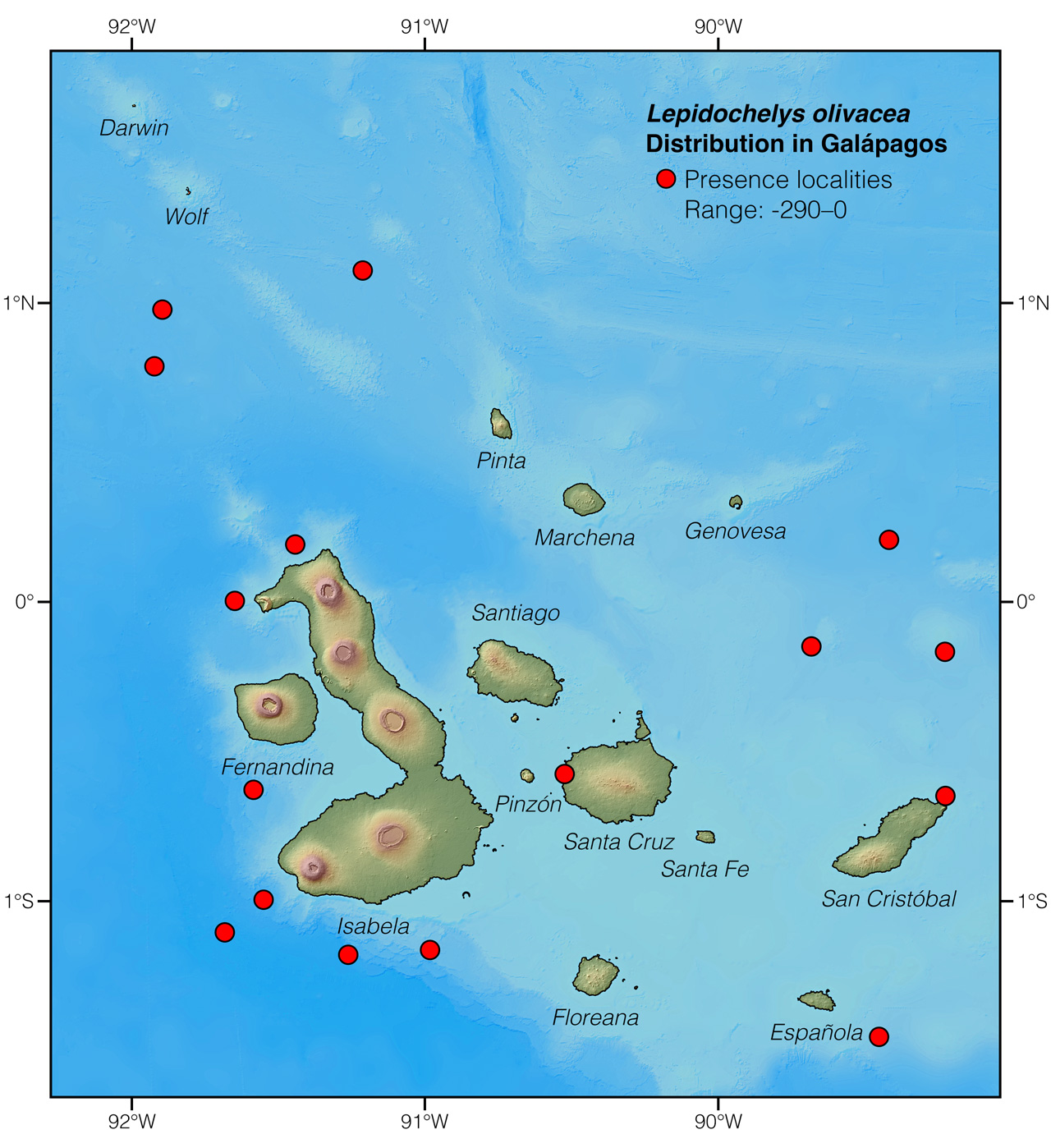

Natural history: Extremely common along the coast of mainland Ecuador, where it is the most common sea turtle species. Rare in Galápagos. After hatching on tropical beaches, hatchlings of Lepidochelys olivacea frantically swim for 1–3 days in an offshore direction until they reach open ocean "nursery" habitats where they spend several years actively swimming and drifting along with surface currents.1,2 During this early stage, the young L. olivacea spend 78% of the day diving at depths of 100–150 cm.2 At night, they spend most of their time floating on the surface.2 Around the world, Olive Ridley Turtle hatchlings are preyed upon by mammals (including whales, dogs, and coyotes), a variety of bird species, iguanas, lizards, snakes, Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea), crocodiles, sharks, fish, and crabs.3–5

After the semi-passive drifting post-hatchling life stage, juvenile and adult Olive Ridley Turtles become nomads of vast oceanic areas2 or establish their foraging ranges in 23–31°C waters6,7 within 15 km of mainland shores.3 From this point onwards, the young Lepidochelys olivacea become opportunistic generalist2 predators of both deep water and surface prey,6 such as fish and their eggs, crustaceans (including crabs, lobsters, shrimp, and barnacles), sea urchins, mollusks (including squid, bivalves, and snails), jellyfish, bryozoans, planktonic tunicates, sea squirts, marine worms, and algae.6,8–10

Olive Ridley Turtles spend up to 98% of their time conducting 10–50 m deep dives near the sea bottom,11 although they can dive down to 290 m and for up to three hours.12 During the remaining time, they bask on the water surface.3 Some adults of Lepidochelys olivacea are residents of 138–1,260 km2 foraging home ranges in coastal waters.11 Others are mostly migratory. They use major oceanic currents6 to travel (probably using geomagnetic cues) up to 83 km per day13 to distant (up to 7,282 km away)6 rookeries, foraging grounds, or nesting beaches.

Olive Ridley Turtles become sexually mature at 13–16 years old.14,15 From this age on, they gather for months16 in polyandrous (a female copulates with more than one male)17 breeding rookeries in shallow waters 2–5 km from the nesting beaches.18 Here, copulation takes place at depths of 0–28 m.18 Hybridization between Lepidochelys olivacea and other sea turtle species such as Caretta caretta,19 Chelonia mydas,20 and Eretmochelys imbricata,21 occurs. Female Olive Ridley Turtles are capable of storing sperm throughout the breeding season,22 and in some populations 31–92% of the resulting clutches are sired by multiple males.23 They nest every 1–8 (but usually every 1–3) years3,24 on roughly (less than 5.6 km apart)25 the same beaches season after season, which may also be the same beaches on which they themselves hatched. Females may also sometimes select different beaches up to 320 km apart.24

Along the coast of mainland Ecuador but not in Galápagos, nesting females can be seen throughout the year, but most nest during the rainy season (from December to May) with a peak in February.26 Others migrate from Mexican and Central American nesting grounds to forage in large numbers in Ecuadorian waters about ~48–64 km from the coast.27

During a single season, females may lay 1–3 clutches3 at intervals of 4–75 (but usually 12–23) days.11,28 They produce 17–182 eggs per clutch3,29 and lay them on sandy beaches with high humidity levels.29 The eggs are laid in 21–69 cm deep30 nests in sand or soil,4 usually at night9,31 but also during the daytime.3 In Lepidochelys olivacea, nesting emergences last 45–60 minutes.4,32 The process may be solitary,23 as it is in Ecuador, or occur in huge in aggregations known as arribadas, with as many as ~800,000 females nesting over 7–8 consecutive nights.33 The incubation period is 48–70 days,4 and 0.8–88% of the eggs hatch.4,34 Temperature determines the sex of the offspring.35 The proportion of female hatchlings increases with incubation temperature.36

At nesting grounds throughout the world, eggs of Lepidochelys olivacea are preyed upon mostly by mammals (including pigs, dogs, dingoes, jackals, coyotes, hyenas, domestic cats, mongooses, raccoons, coatis, and opossums), but also by caracaras, caimans, crocodiles, lizards, snakes, crabs, and beetles.4,5,37 They are also occasionally lost to erosion,38 inundation,38 and disturbance by other nesting turtles.2 The eggs are also widely harvested for human consumption2 (although they may cause food poisoning).3 The eggs hatch synchronously and usually at night or late in the afternoon.39 During nocturnal emergence, the presence of artificial lighting affects the orientation of hatchlings, which may result in mortality caused by traffic, desiccation, and starvation.40

In addition to predation by sharks,41 large fish,42 crocodiles,43 whales,42 coyotes,3 and jaguars,44 causes of mortality of adult Olive Ridley Turtles include ingestion of plastic,45 collision with boats,26 interactions with fishing gear,46, direct harvesting for meat consumption (although their meat may cause food poisoning),3 and harvesting for the leather market.26 Individuals of Lepidochelys olivacea are parasitized by a variety of worms47 and leeches48 and colonized by barnacles, amphipod crustaceans, crabs, remoras, and hydrozoans.10,48,49 Turtles of this species are estimated to live up to 40 years.3

Conservation: Vulnerable.50 Lepidochelys olivacea is listed in this category because its global populations have declined 31–36% over the past three generations as a result of direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, incidental mortality due to interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.50 Another threat faced by L. olivacea is the increase of the average global temperature, which may result in the complete feminization of some populations and the large-scale mortality of embryos due to lethal field temperatures.51 Under some scenarios of global sea level rise, up to 43% of the area of some L. olivacea nesting beaches may be lost by 2100.52

In the waters off the coast of mainland Ecuador, Lepidochelys olivacea is also under threat. Olive Ridley Turtles make up the majority of the bycatch of artisanal fisheries in Ecuador.53 Additionally, they were the most heavily exploited sea turtle in the country during the 1970s, with ~100,000–148,000 individuals per year slaughtered for consumption and the leather market.26,54 Finally, enigmatic mass mortality events of Olive Ridleys attributed to several causes such as bycatch, sea surface temperature anomalies, and outbreaks/diseases have also been reported to have occurred along the Ecuadorian coast during the past decade.55

Distribution: Tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

Etymology: The generic name Lepidochelys, which comes from the Greek words lepidos (meaning “scale”) and chelys (meaning “turtle”),56 is probably a reference to the scutes covering the carapace. The specific epithet olivacea, which comes from the Latin word oliva (meaning “olive tree”),56 refers to the color of the carapace.

See it in the wild: Although members of Lepidochelys olivacea nest along the coast of mainland Ecuador, roughly on the same beaches during the same months, witnessing such events is rare. However, swimming Olive Ridley Turtles can be seen with ~40–60% certainty while navigating on motorized boats off the coast of Machalilla National Park. However, this species cannot be expected to be seen reliably in Galápagos, since individuals transiting through the archipelago's waters are rarely spotted and there are no records of females nesting on the islands.

FAQ

How did the Olive Ridley Sea Turtle become endangered? The Olive Ridley Sea Turtle is considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future because its populations have declined 31–36% over the past three generations as a result of direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, incidental mortality due to interactions with fisheries, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.50

How many eggs do Olive Ridley Sea Turtles lay? Olive Ridley Sea Turtles lay 17–182 eggs per clutch.3,29

What do Olive Ridley Sea Turtles eat? Olive Ridley Sea Turtles are generalist opportunistic predators. They feed on fish and their eggs, crustaceans, sea urchins, mollusks, jellyfish, bryozoans, planktonic tunicates, sea squirts, marine worms, and algae.6,8–10

What does arribada mean? Arribada is a mass nesting behavior of some sea turtle species such as the Olive Ridley Turtle in which thousands of females nest on the same beach over a short period of time. Arribadas do not take place in Ecuador, only solitary nesting.

Where is the Olive Ridley Sea Turtle found? Olive Ridley Sea Turtles occur in tropical and subtropical waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

Which is the world's most important nesting beach for Olive Ridley Sea Turtles? Gahirmatha Beach in eastern India is the world's most important nesting beach for Olive Ridley Sea Turtles. As many as 800,000 females nest on this beach over 7–8 consecutive nights.33

Why do Olive Ridley Sea Turtles lay so many eggs? Olive Ridley Sea Turtles have evolved to lay many eggs in order to improve the chances of an egg hatching and surviving into adulthood, since the majority (up to 99%) of the hatchlings are likely to perish before reaching maturity.

Why do Olive Ridley Turtles migrate? Olive Ridley Turtles routinely migrate between feeding and breeding areas because the most productive feeding grounds are usually not near the most suitable nesting beaches. Breeding gatherings may last months16 and usually take place in areas where food is scarce. Thus, the turtles spend most of their remaining time growing their energy reserves in distant feeding grounds.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Juan José Alava.

Photographers: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Lepidochelys olivacea. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Boyle MC (2006) Post-hatchling sea turtle biology. PhD thesis, Townsville, Australia, James Cook University.

- Duran Royo N (2015) Reproductive ecology and hatchling behavior of olive ridley sea turtles in Honduras. PhD thesis, Loma Linda, United States, Loma Linda University.

- Ernst CH, Lovich JE (2009) Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 840 pp.

- Hughes DA, Richard JD (1974) The nesting of the Pacific ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) on Playa Nancite, Costa Rica. Marine Biology 24: 97–107.

- Whiting SD, Whiting AU (2011) Predation by the Saltwater Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) on sea turtle adults, eggs, and hatchlings. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 10: 198–205.

- Polovina JJ, Balazs GH, Howell EA, Parker DM, Seki MP, Dutton PH (2004) Forage and migration habitat of loggerhead (Caretta caretta) and olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) sea turtles in the central North Pacific Ocean. Fisheries Oceanography 13: 36–51.

- Behera S, Tripathy B, Choudhury BC, Sivakumar K (2018) Movements of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) in the Bay of Bengal, India, determined via satellite telemetry. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 17: 44–53.

- Bjorndal KA (1997) Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles. In: Musick JA, Lutz PL (Eds) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 199–231.

- De Cajas L (2001) Contenido estomacal de la tortuga marina Lepidochelys olivacea. Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Guayaquil, 1 p.

- Fritts TH (1981) Marine turtles of the Galápagos Islands and adjacent areas of the Eastern Pacific on the basis of observations made by J. R. Slevin 1905-1906. Journal of Herpetology 15: 293–301.

- Whiting SD, Long JL, Coyne M (2007) Migration routes and foraging behaviour of olive ridley turtles Lepidochelys olivacea in northern Australia. Endangered Species Research 3: 1–9.

- Musick JA, Lutz PL (1997) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 446 pp.

- Schulz JP (1975) Sea turtles nesting in Surinam. Zoologische Verhandelingen, uitgegeven door het Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie te Leiden 143: 1–144.

- Zug GR, Chaloupka M, Balazs GH (2006) Age and growth in olive ridley seaturtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) from the North-central Pacific: a skeletochronological analysis. Marine Ecology 27: 263–270.

- Petitet R, Avens L, Castilhos JC, Kinas PG, Bugoni L (2015) Age and growth of olive ridley sea turtles Lepidochelys olivacea in the main Brazilian nesting ground. Marine Ecology Progress Series 541: 205–218.

- Behera S, Tripathy B, Choudhury BC, Sivakumar K (2010) Behaviour of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) prior to arribada at Gahirmatha, Orissa, India. Herpetology Notes 3: 273–274.

- Hoekert WEJ, Neuféglise H, Schouten AD, Menken SBJ (2002) Multiple paternity and female-biased mutation at a microsatellite locus in the olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). Heredity 89: 107–113.

- Tripathy B (2013) Distribution and dynamics of reproductive patch in olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) off Rushikulya, Orissa coast of India. Indian Journal of Geo-Marine Sciences 42: 343–348.

- Reis EC, Soares LS, Lôbo-Hajdu G (2010) Evidence of olive ridley mitochondrial genome introgression into loggerhead turtle rookeries of Sergipe, Brazil. Conservation Genetics 11: 1587–1591.

- Seminoff JA, Karl SA, Schwartz T, Resendiz A (2003) Hybridization of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Pacific Ocean: indication of an absence of gender bias in the directionality of crosses. Bulletin of Marine Science 73: 643–652.

- Lara-Ruiz P, Lopez GG, Santos FR, Soares LS (2006) Extensive hybridization in hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting in Brazil revealed by mtDNA analyses. Conservation Genetics 7: 773–781.

- Chavez A, Arana M, Du Toit L (2000) Primary evidence of sperm storage in the ovaries of the olive ridley marine turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). NOAA Technical Memorandum, Mazatlán, 123 pp.

- Bowen BW, Karl SA (2007) Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Molecular Ecology 16: 4886–4907.

- Tripathy B, Pandav B (2007) Beach fidelity and internesting movements of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) at Rushikulya, India. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 3: 40–45.

- Matos L, Silva ACCD, Castilhos JC, Weber MI, Soares LS, Vicente L (2012) Strong site fidelity and longer internesting interval for solitary nesting olive ridley sea turtles in Brazil. Marine Biology 159: 1011–1019.

- Green D, Ortiz-Crespo F (1981) The status of sea turtle populations in the central eastern Pacific. In: Bjorndal K (Ed) Biology and conservation of sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. and London, 221–233.

- Hurtado M (1981) Marine turtles recaptured in Ecuadorian waters. Boletín Informativo del Instituto Nacional de Pesca 2: 18–23.

- Minarik CJ (1985) Lepidochelys olivacea (olive ridley sea turtle): reproduction. Herpetological Review 16: 82.

- López-Castro MC, Carmona R, Nichols WJ (2004) Nesting characteristics of the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) in Cabo Pulmo, southern Baja California. Marine Biology 145: 811–820.

- Dunbar SG, Salinas L, Castellanos S (2011) Activities of the Protective Turtle Ecology Center for Training, Outreach, and Research, INC in the Golf of Fonseca, Honduras. Ministry of Environment, Tegucigalpa, 57 pp.

- Plotkin PT, Byles RA, Rostal DC, Owens DW (1995) Independent versus socially facilitated oceanic migrations of the olive ridley, Lepidochelys olivacea. Marine Biology 122: 137–143.

- Spotila JR (2004) Sea turtles: a complete guide to their biology, behavior, and conservation. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 227 pp.

- Tripathy B (2002) Is Gahirmatha the world's largest sea turtle rookery? Current Science 83: 1299–1299.

- Cornelius SE, Ulloa MA, Castro JC, Mata del Valle M, Robinson DC (1991) Management of olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting at Playas Nancite and Ostional, Costa Rica. In: Robinson JG, Redford KH (Eds) Neotropical wildlife use and conservation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 111–135.

- Mrosovsky N (1994) Sex ratios of sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270: 16–27.

- Standora EA, Spotila JR (1985) Temperature dependent sex determination in sea turtles. Copeia 1985: 711–712.

- Chatto R, Baker B (2008) The distribution and status of marine turtle nesting in the Northern Territory. Parks and Wildlife Service, Palmerston, 309 pp.

- Behera S, Sivakumar K, Choudhury BC, Tripathy B, Kar CS (2012) Occurrence of olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) solitary nests and their future conservation implications in Gahirmatha rookery, Odisha, India. Indian Forester 138: 869–875.

- Drake DL, Spotila JR (2002) Thermal tolerances and the timing of sea turtle hatchling emergence. Journal of Thermal Biology 27: 71–81.

- Karnad D, Isvaran K, Kar CS, Shanker K (2009) Lighting the way: towards reducing misorientation of olive ridley hatchlings due to artificial lighting at Rushikulya, India. Biological Conservation 142: 2083–2088.

- Witzell WN (1987) Selective predation on large Cheloniid sea turtles by tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier). Japanese Journal of Herpetology 12: 22–29.

- NOAA (2014) Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, 81 pp.

- Ortiz RM, Plotkin PT, Owens PW (1997) Predation on olive ridley sea turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) by the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) at Playa Nancite, Costa Rica. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 2: 585–587.

- Alfaro LD, Montalvo V, Guimarães F, Sáenz C, Cruz J, Morazan F, Carrillo E (2016) Characterization of attack events on sea turtles (Chelonia mydas and Lepidochelys olivacea) by jaguar (Panthera onca) in Naranjo sector, Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. International Journal of Conservation Science 7: 101–108.

- Mascarenhas R, Santos R, Zeppelini D (2004) Plastic debris ingestion by sea turtle in Paraíba, Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin 49: 354–355.

- Adimey NM, Hudak CA, Powell JR, Bassos-Hull K, Foley A, Farmer NA, White L, Minch K (2014) Fishery gear interactions from stranded bottlenose dolphins, Florida manatees and sea turtles in Florida, U.S.A. Marine Pollution Bulletin: 81: 103–115.

- Santoro M, Morales JA (2007) Some digenetic trematodes of the olive ridley sea turtle, Lepidochelys olivacea (Testudines, Cheloniidae) in Costa Rica. Helminthologia 44: 25–28.

- Gámez VS, Osorio SD, Peñaflores SC, García HA, Ramírez LJ (2006) Identification of parasites and epibionts in the Olive Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) that arrived to the beaches of Michoacan and Oaxaca, Mexico. Veterinaria México 37: 431–440.

- Miranda L, Moreno RA (2002) Epibiontes de Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) (Reptilia: Testudinata: Cheloniidae) en la región centro sur de Chile. Revista de Biología Marina y Oceanografía 37: 145–146.

- Abreu-Grobois A, Plotkin P (2008) Lepidochelys olivacea. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Valverde RA, Wingard S, Gómez F, Tordoir MT, Orrego CM (2010) Field lethal incubation temperature of olive ridley sea turtle Lepidochelys olivacea embryos at a mass nesting rookery. Endangered Species Research 12: 77–86.

- Patrício AR, Varela MR, Barbosa C, Broderick AC, Catry P, Hawkes LA, Regalla A, Godley BJ (2018) Climate change resilience of a globally important sea turtle nesting population. Global Change Biology 25: 522–535.

- Alava JJ (2000) Current conservation status of Sea Turtles in Ecuador. In: Amorocho D, Campo F, Riascos JA, Parra E (Eds) Proceedings of the Workshop about Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles and III International Seminar of the Colombian Network for the Sea Turtles Conservation. RETOMAR–WIDECAST, Colombia, 51–58.

- Carr AF (1984) So excellent a fishe. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 280 pp.

- Alava JJ, Jiménez P, Peñafiel M, Aguirre W, Amador P (2005) Sea turtle strandings and mortality in Ecuador: 1994–1999. Marine Turtle Newsletter 108: 4–7.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.