Loggerhead |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Cheloniidae | Caretta caretta

English common names: Loggerhead, Loggerhead Sea-Turtle.

Spanish common name: Caguama, tortuga boba, cayume, cabezona.

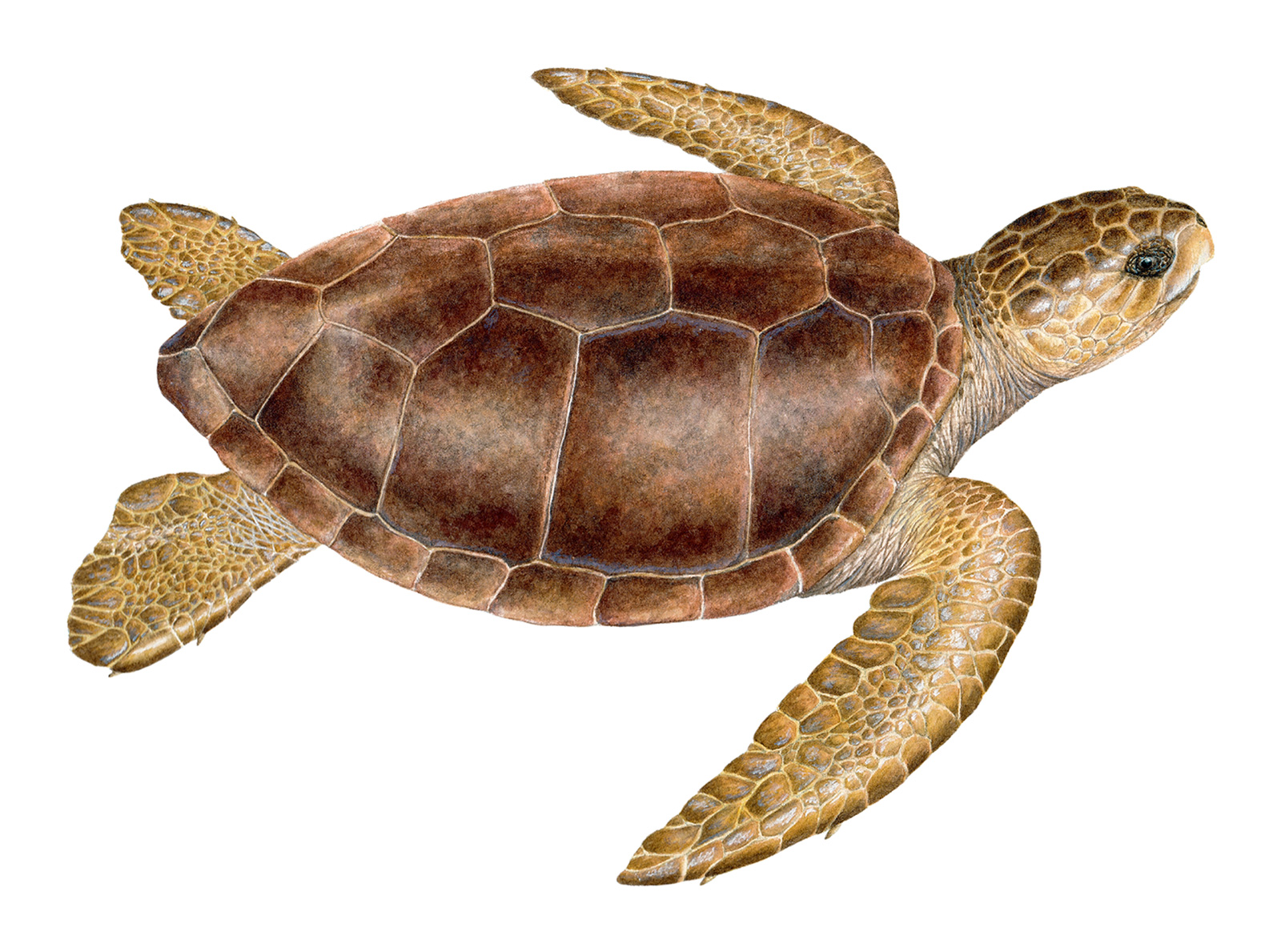

Recognition: ♂♂ 125 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 213 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace.. The Loggerhead (Caretta caretta) is unique among sea turtles in Ecuador because it haves five pairs of costal shields, and a distinctly reddish brown carapace coloration. Adult males are much smaller than females, have longer and thicker tails, and have enlarged claws on the flippers, which they use to grasp females during copulation.

Illustration. Adult female. | |

| |

Illustration. Juvenile. | |

| |

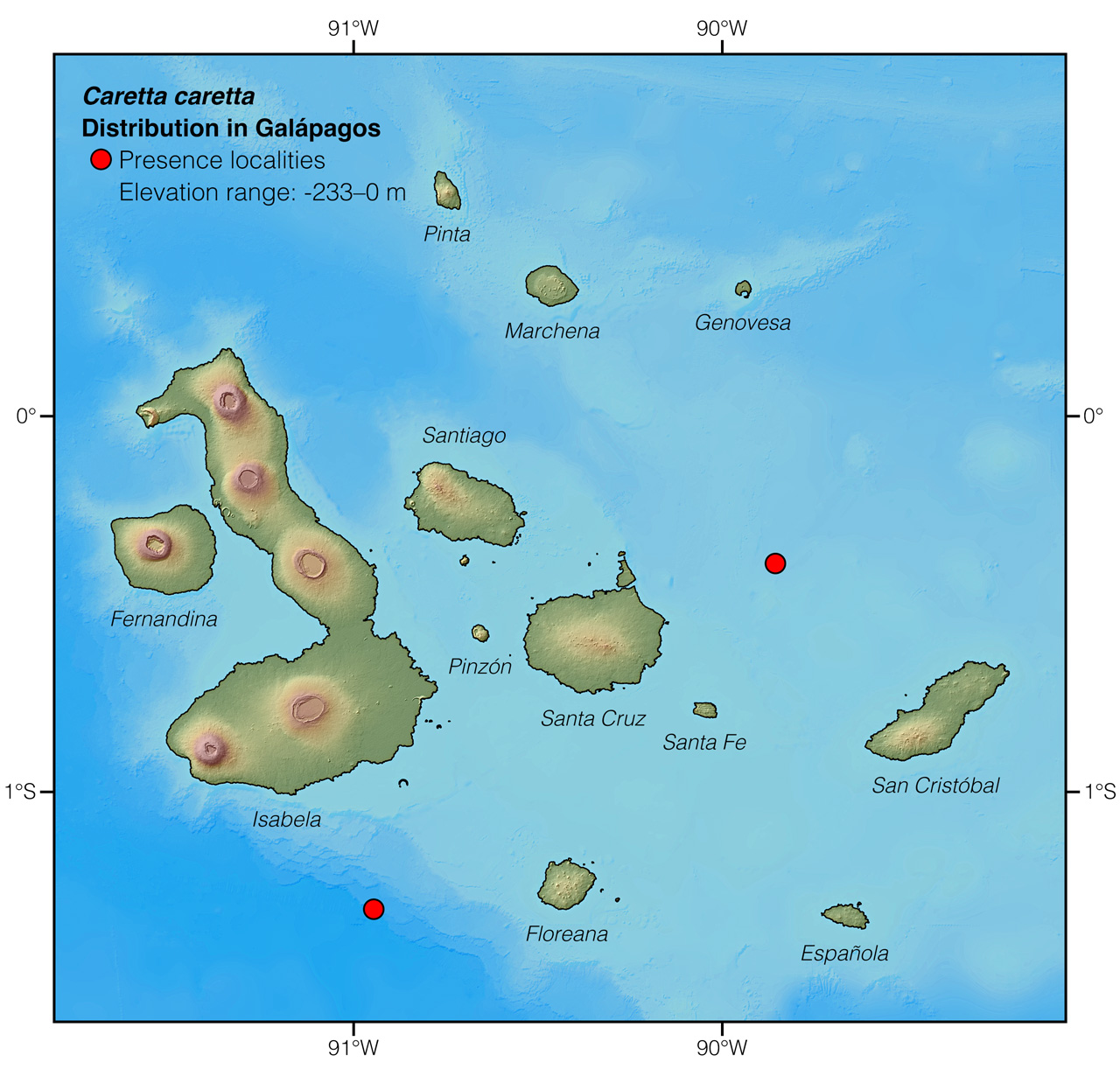

Natural history: Extremely rare in Galápagos. After hatching on tropical and subtropical beaches,1 hatchlings of Caretta caretta frantically swim for 1–3 days in an offshore direction2 until they reach open ocean "nursery" habitats where they spend 6.5–11.5 years,3 drifting and actively swimming along with surface currents,4 usually in association with masses of floating seaweed.1 During this early stage, the young C. caretta spend 80% of their time within 5 m from the surface.5 These post-hatchling C. caretta are mostly carnivorous, feeding primarily on pelagic jelly organisms until they become large enough to dive and feed on bottom-dwelling prey.6 At nesting grounds throughout the world, hatchlings of the Loggerhead Sea-Turtle are preyed upon by a variety of animals. On land, they are preyed upon by mammals (for example, dogs, foxes, house cats, mongooses, raccoons, and genets), a variety of birds, lizards, snakes, toads, and ants.1,7 In the water, they are preyed upon by monk seals, killer whales, fish, sharks, squid, and crabs.1,7

When they reach a carapace length of 42–59 cm,8 most Loggerheads establish their home ranges on hard- and soft-bottom habitats in shallower waters near the coast.1 Others may remain in or reenter the oceanic environment.9 From this age onwards, the young Caretta caretta become generalist opportunistic predators of both deep water and surface prey, including sponges, cnidarians (jellyfish, hydrozoans, sea anemones, whip corals, and sea pens), annelids (bristle worms and tube worms), mollusks (squid, octopuses, sea snails, and bivalves), arthropods (horseshoe crabs, amphipod crustaceans, isopods, barnacles, crabs, shrimp, and insects), bryozoans, echinoderms (cake urchins, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers), tunicates, fish and their eggs, sea horses, members of their own species, algae, and terrestrial plants.1,7 Presumably as a result of this diet, C. caretta is biofluorescent, although part of the fluorescence is likely emitted by algae living on the turtles.10

Loggerheads spend up to 86–95% of their time (day and night) submerged, mostly diving near the surface,11–13 although they can dive to 233 m in depth14 and for up to eight hours.15 They spend the remaining time floating,1 basking,16 foraging at the sea bottom,6 or resting.16 Loggerhead Sea Turtles rest on the seabed16 or wedged between coral or rock ledges in shallow (0–30 m deep) water,1,15 surfacing for air every 10–56 minutes.1 In the open ocean, Loggerheads sleep while floating.1 Some adults of Caretta caretta are residents of 954–28,833 km2 foraging home ranges including coastal and oceanic waters.11 They may also enter mangrove estuaries, lagoons, salt marshes, creeks, and the mouths of large rivers.7

Adults of Caretta caretta are capable of migrating long distances with the aid of geomagnetic cues.7 They swim actively and also passively drift along with major oceanic currents17 to distant (up to 11,512 km away)17 rookeries, foraging grounds, or nesting beaches.18 In areas where the water temperature is 12–15°C during winter months,15 some Loggerhead Sea Turtles (those that don’t migrate into warmer regions) spend most of their time in a state of dormancy at the sea bottom at depths of 20–30 m.15

Loggerheads become sexually mature at 24–29 years old.19 Some gather in polygamous (mating with multiple partners)20 breeding rookeries21 in shallow waters not necessarily close to the nesting beaches,1 while others mate in the open ocean.7 Copulation takes place on the water's surface1 and may last for up to 320 minutes (over five hours).22 Hybridization between C. caretta and other sea turtle species such as Chelonia mydas,23 Eretmochelys imbricata,24 and Lepidochelys olivacea,25 occurs. Females of the Loggerhead are capable of storing sperm throughout the breeding season,20 and, in some populations, 33–94% of the resulting clutches are sired by multiple males.26

Females of Caretta caretta nest every 1–9 years1 on roughly (less than 5 km apart)27 the same beaches season after season,1 which may also be the same beaches on which they themselves hatched.28 Others may sometimes select different beaches up to 725 km apart.1 The nesting season generally coincides with summer at times of plentiful rainfall,1 but Loggerheads do not nest in Ecuador. During a single season, Loggerhead Sea-Turtle females may lay 1–6 clutches1 at intervals of 9–34 (but usually 12–15)29 days.1,29 They produce 39–198 eggs per clutch1 and lay them mostly on continental, or, less frequently, on insular beaches in 35–85 cm deep nests in the sand,1 either in the open or among shrubs and grasses behind the beach.7 Nesting emergences typically last 45–150 minutes1 and take place at night or early in the morning.21 During emergences, female Loggerheads are very shy, and can be easily scared back into the sea.1

Nesting in Caretta caretta is solitary,1 with no more than seven turtles nesting on the same stretch (1 km long) of beach on the same night.30 The eggs' incubation period is 46–102 days7 and an average of 53–84% of the eggs hatch.1 Temperature determines the sex of the offspring.31 The proportion of female hatchlings increases with the incubation temperature.32 Eggs of C. caretta are preyed upon by a variety of animals at nesting grounds throughout the world. Predators include mammals (pigs, dogs, jackals, foxes, dingoes, honey badgers, skunks, raccoons, bears, armadillos, and rats), birds (crows and gulls), reptiles (monitor lizards and snakes), arthropods (crabs, beetles, fly larvae, wasp larvae, and ants), and worms.1,7 They are also occasionally lost to erosion, inundation, invasion of nests by plant roots, disturbance by other nesting turtles, and off-road vehicles crushing nests. The eggs are also widely harvested by humans for food.1,7

Loggerhead Sea-Turtle eggs usually hatch at night, early morning, or late in the afternoon, but not necessarily in synchrony.1,7 Some hatchlings are unable to dig their way out of the nest and perish.7 During nocturnal emergence, the presence of artificial lighting affects the orientation of hatchlings,7 which may result in mortality caused by traffic, dehydration, exhaustion, or predation.33,34 During diurnal emergence, desiccation can also cause hatchling mortality.35 It is estimated that less than 0.1% of the hatchlings reach adulthood.36

In addition to predation by sharks, large fish, and dogs,1 causes of mortality of adult Loggerheads include red tides, ingestion of plastic, collision with boats, interactions with fishing gear, direct harvesting for meat consumption (although their meat may cause food poisoning),37 and oil spills.1,38–40 Individuals of Caretta caretta are parasitized by a variety of worms and leeches, and are colonized by cnidarians (including hydrozoans, sea anemones, sea whips, and hard coral), mollusks (such as bivalves and sea snails), bristle worms, arthropods (for example, barnacles, amphipods, isopods, and crabs), bryozoans, tunicates, remoras, and algae.1 The estimated maximum lifespan of members of C. caretta is 67 years.41

Conservation: Vulnerable.42 Caretta caretta is listed in this category because its populations have declined 47% over the past three generations as a result of incidental mortality due to interactions with small-scale and industrial fisheries, direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, and the degradation of marine and nesting habitats.42,43 Another threat faced by C. caretta is climate change.44,45 Since temperature during incubation determines the sex of the offspring,31 the increase of the average global temperature may result in the complete feminization of some populations.44 Under some scenarios of global sea level rise, up to 67% of clutches in some nesting beaches may be lost to flooding by 2100.45

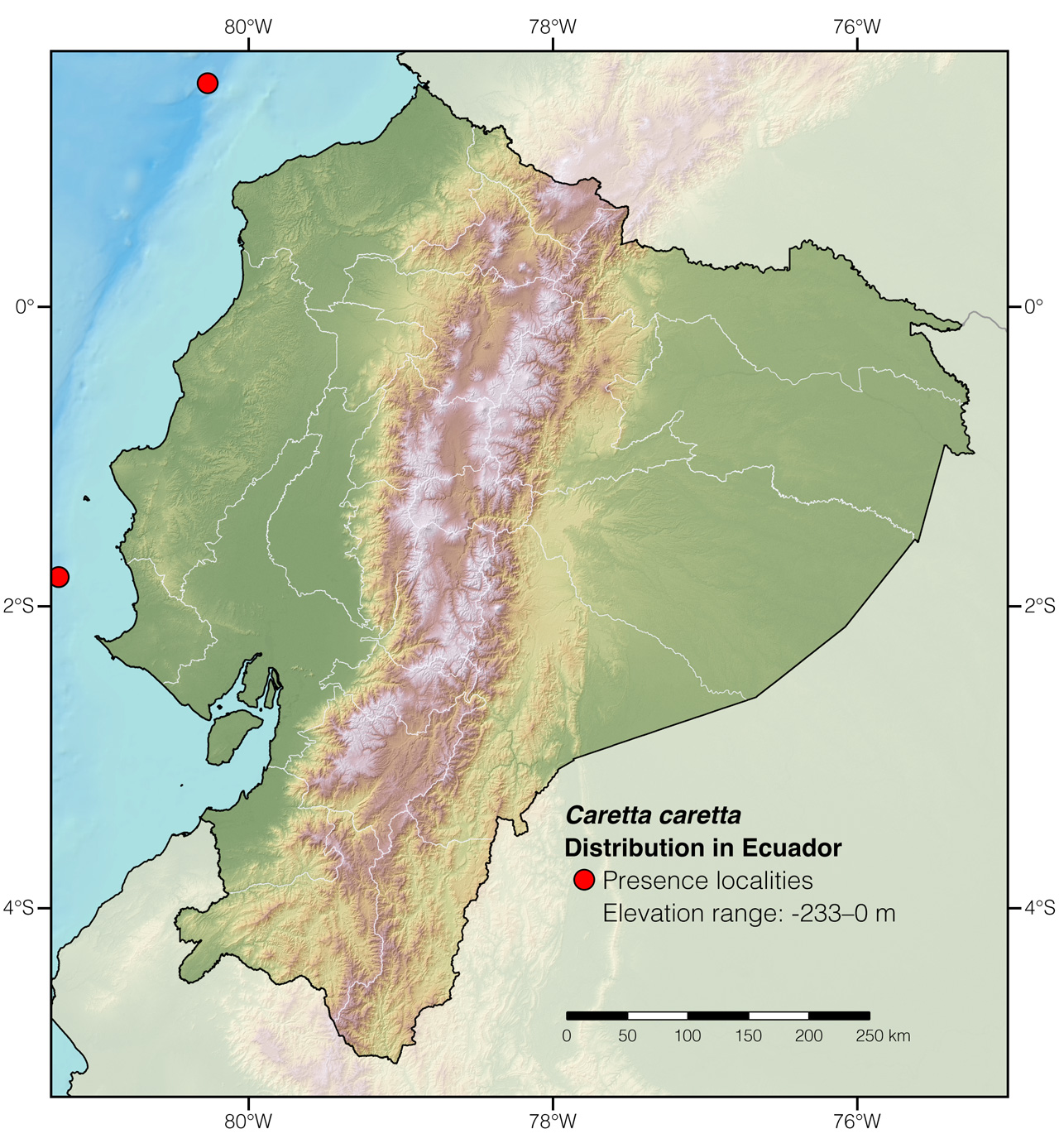

Distribution: Loggerhead Sea Turtles occur throughout the tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

"Vessel drifting way to the south. Seldom any wind and what there is, extremely light. Current carried us out of sight of the islands altogether. Nothing of any note happened until today, May 11th; we caught a loggerhead turtle sleeping on the water. This is the first seen in the Galapagos."

Joseph Slevin, researcher at the California Academy of Sciences, 1906.46

Etymology: Both the generic name and specific epithet are derived from the French word caret (meaning “turtle”).47

See it in the wild: Caretta caretta cannot be expected to be seen reliably along the coast of mainland Ecuador and Galápagos, since individuals presumably arrive to Ecuadorian waters no more than once every few years.

Special thanks to Courtney Bultemeier for symbolically adopting the Loggerhead Sea Turtle and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Juan José Alava.

Illustrator. Valentina Nieto Fernández.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Caretta caretta. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

FAQ

Are Loggerhead Turtles dangerous? No. Although there have been cases of Loggerheads biting swimmers,48 the turtles' diet does not include humans, and their bites do not represent a serious threat to people.

Do Loggerheads live in groups? They do not. Loggerheads are solitary throughout most of their lives, congregating only to mate.1

Do Loggerhead Turtles bite? Yes. Although Loggerhead Sea Turtles do not feed on humans, there have been cases of Loggerheads biting swimmers,48 although these bites represent no serious threat.

Do Loggerhead Turtles need freshwater? They don't. They survive drinking only seawater, which they are able to desalinize by means of specialized "salt glands" located behind the turtles' eyes.49

How can you help Loggerhead Sea Turtles? The best way you can help ensure a future for Loggerhead Sea Turtles is by supporting or volunteering at conservation organizations such as Sea Turtle Conservancy.

How do Loggerhead Sea Turtles navigate? Loggerheads navigate using the earth's magnetic field not only as a cue for compass orientation but also as a source of world-wide positional information.50

How long can Loggerhead Sea Turtles stay underwater? The maximum recorded duration of a Loggerhead's voluntary dive is eight hours.15

What do Loggerhead Turtles eat? Loggerhead Turtles are carnivorous. They feed on sponges, cnidarians (jellyfish, hydrozoans, sea anemones, whip corals, and sea pens), annelids (bristle worms and tube worms), mollusks (squid, octopuses, sea snails, and bivalves), arthropods (horseshoe crabs, amphipod crustaceans, isopods, barnacles, crabs, shrimp, and insects), bryozoans, echinoderms (cake urchins, sea urchins, and sea cucumbers), tunicates, fish and their eggs, sea horses, members of their own species, algae, and terrestrial plants.1,7

What is a group of turtles called? A bale of turtles.

Where do Loggerheads nest? Major Loggerhead nesting grounds are located in warm temperate and subtropical regions, most notably in the southeastern United States and the Mediterranean Sea. Nesting in the tropics is mostly scattered or non-existent.1

Why are Loggerhead Sea Turtles called Loggerheads? Loggerheads are named after their distinctive large heads, which are comparatively larger than those of most other sea turtles'. Their large heads support the powerful jaws they need to feed on heavily armored prey.

Literature cited:

- Dodd CK (1988) Synopsis of the biological data on the loggerhead sea turtle Caretta caretta (Linnaeus 1758). Biological Report 88: 1–110.

- Boyle MC (2006) Post-hatchling sea turtle biology. PhD thesis, Townsville, Australia, James Cook University.

- Bjorndal KA, Bolten AB, Martins HR (2000) Somatic growth model of juvenile loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta: duration of pelagic stage. Marine Ecology Progress Series 202: 265–272.

- Briscoe DK, Parker DM, Balazs GH, Kurita M, Saito T, Okamoto H, Rice M, Polovina JJ, Crowder LB (2016) Active dispersal in loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) during the "lost years." Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283: 20160690.

- Howell E, Dutton P, Polovina J, Bailey H, Parker D, Balazs G (2010) Oceanographic influences on the dive behavior of juvenile loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) in the North Pacific Ocean. Marine Biology 157: 1011–1026.

- Bjorndal KA (1997) Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles. In: Musick JA, Lutz PL (Eds) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 199–231.

- Ernst CH, Lovich JE (2009) Turtles of the United States and Canada. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 840 pp.

- McClellan CM, Read AJ (2007) Complexity and variation in loggerhead sea turtle life history. Biology Letters 3: 592–594.

- Dalleau M, Behamou S, Sudre J, Ciccione S, Bourjea J (2013) Movement and diving behavior of late juvenile loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Western Indian Ocean. Indian Ocean Tuna Comission, Denpasar, 44 pp.

- Gruber DF, Sparks JS (2015) First observation of fluorescence in marine turtles. American Museum Novitates 3845: 1–8.

- Renaud ML, Carpenter JA (1994) Movements and submergence patterns of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Gulf of Mexico determined through satellite telemetry. Bulletin of Marine Science 55: 1–15.

- Patel SH, Dodge KL, Haas HL, Smolowitz RJ (2016) Videography reveals in-water behavior of loggerhead turtles (Caretta caretta) at a foraging ground. Frontiers in Marine Science 3: 254.

- Lutcavage ME, Lutz PL (1991) Voluntary diving metabolism and ventilation in the loggerhead sea turtle. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 147: 287–296.

- Musick JA, Lutz PL (1997) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 446 pp.

- Hochscheid S, Bentivegna F, Bradai MN, Hays GC (2007) Overwintering behaviour in sea turtles: dormancy is optional. Marine Ecology Progress Series 340: 287–298.

- Schofield G, Katselidis KA, Dimopoulos P, Pantis JD, Hays GC (2006) Behaviour analysis of the loggerhead sea turtle Caretta caretta from direct in-water observation. Endangered Species Research 3: 71–79.

- Nichols WJ, Resendiz A, Seminoff JA, Resendiz B (2000) Transpacific migration of a loggerhead turtle monitored by satellite telemetry. Bulletin of Marine Science 67: 937–947.

- Bolten AB (2003) Active swimmers – passive drifters: the oceanic juvenile stage of loggerheads in the Atlantic system. In: Bolten AB, Witherington BE (Eds) Loggerhead sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C, 63–78.

- Casale P, Mazaris AD, Freggi D (2011) Estimation of age at maturity of loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta in the Mediterranean using length-frequency data. Endangered Species Research 13: 123–129.

- Pearse DE, Avise JC (2001) Turtle mating systems: behavior, sperm storage, and genetic paternity. Journal of Heredity 92: 206–211.

- Caldwell DK, Carr A, Ogren LH (1959) The Atlantic loggerhead sea turtle, Caretta caretta (L.) in America. I. Nesting and migration of the Atlantic loggerhead turtle. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 4: 293–308.

- Wood FG (1953) Mating behavior of captive loggerhead turtles, Caretta caretta caretta. Copeia 1953: 184–186.

- James MC, Martin K, Dutton PH (2004) Hybridization between a green turtle, Chelonia mydas, and loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta, and the first record of a green turtle in Atlantic Canada. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 118: 579–582.

- Karl SA, Bowen BW, Avise JC (1995) Hybridization among the ancient mariners: characterization of marine turtle hybrids with molecular genetic assays. Journal of Heredity 86: 262–268.

- Reis EC, Soares LS, Lôbo-Hajdu G (2010) Evidence of olive ridley mitochondrial genome introgression into loggerhead turtle rookeries of Sergipe, Brazil. Conservation Genetics 11: 1587–1591.

- Bowen BW, Karl SA (2007) Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Molecular Ecology 16: 4886–4907.

- Tucker AD (2010) Nest site fidelity and clutch frequency of loggerhead turtles are better elucidated by satellite telemetry than by nocturnal tagging efforts. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 383: 48–55.

- Bowen BW, Abreu-Grobois FA, Balazs GH, Kamezaki N, Limpus CJ, Ferl RJ (1995) Trans-Pacific migrations of the loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta) demonstrated with mitochondrial DNA markers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 92: 3731–3734.

- Caldwell DK, Berry FH, Carr A, Racotzkie (1959) The Atlantic loggerhead sea turtle, Caretta caretta (L.) in America. II. Multiple and group nesting by the Atlantic loggerhead turtle. Bulletin of the Florida Museum of Natural History 4: 309–318.

- Mendonça VM, Bicho RC, Al Saady SM (2010) Where did the loggerhead Caretta caretta nesting female population of Masirah Island (Arabian Sea) go? Proceedings of the 28th Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation, Loreto, 7 pp.

- Mrosovsky N (1994) Sex ratios of sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270: 16–27.

- Georges A, Limpus C, Stoutjesdijk R (1994) Hatchling sex in the marine turtle Caretta caretta is determined by proportion of development at a temperature, not daily duration of exposure. Journal of Experimental Zoology 270: 432–444.

- McFarlane RW (1963) Disorientation of loggerhead hatchlings by artificial road lighting. Copeia 1963: 153.

- Ehrhart LM, Witherington BE (1987) Human and natural causes of marine turtle nest and hatchling mortality and their relationship to hatchling production on an important Florida nesting beach. Florida Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, Tallahassee, 141 pp.

- Hays GC, Speakman JR (1993) Nest placement by loggerhead turtles, Caretta caretta. Animal Behavior 45: 47–53.

- Frazer NB (1986) Survival from egg to adulthood in a declining population of Loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta. Herpetologica 42: 47–55.

- Venkataraman K, Milton J (2003) Handbook on marine turtles of India. Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata, 87 pp.

- Foley AM, Stacy BA, Schueller P, Flewelling LJ, Schroeder B, Minch K, Fauquier DA, Foote JJ, Manire CA, Atwood KE, Granholm AA, Landsberg JH (2019) Assessing Karenia brevis red tide as a mortality factor of sea turtles in Florida, USA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 132: 109–124.

- Orós J, Montesdeoca N, Camacho M, Arencibia A, Calabuig P (2016) Causes of stranding and mortality, and final disposition of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) admitted to a wildlife rehabilitation center in Gran Canaria Island, Spain (1998-2014): a long-term retrospective study. PLoS ONE 11: e0149398.

- Bugoni L, Krause L, Virgínia Petry M (2001) Marine debris and human impacts on sea turtles in southern Brazil. Marine Pollution Bulletin 42: 1330–1334.

- Frazer NB (1983) Survivorship of adult female loggerhead sea turtles, Caretta caretta, nesting on Little Cumberland Island, Georgia, USA. Herpetologica 39: 436–447.

- Casale P, Tucker AD (2017) Caretta caretta. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Alava JJ (2008) Loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in marine waters off Ecuador: Occurrence, distribution and bycatch from the Eastern Pacific Ocean. Marine Turtle Newsletter 119: 8–11.

- Reneker JL, Kamel SJ (2016) Climate change increases the production of female hatchlings at a northern sea turtle rookery. Ecology 97: 3257–3264.

- Varela MR, Patrício AR, Anderson K, Broderick AC, DeBell L, Hawkes LA, Tilley D, Snape RTE, Westoby MJ, Godley BJ (2018) Assessing climate change associated sea level rise impacts on sea turtle nesting beaches using drones, photogrammetry and a novel GPS system. Global Change Biology 5: 753–762.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin's journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- Uetz P, Freed P, Hošek J (2016) The Reptile Database. Available from: www.reptile-database.org

- DAILY SABAH (2017) Loggerhead sea turtles bite Antalya swimmers off Turkey’s Antalya, mistaking them for jellyfish. Available from: http://www.dailysabah.com

- Bennett JM, Taplin LE, Grigg GC (1986) Sea water drinking as a homeostatic response to dehydration in hatchling loggerhead turtles Caretta caretta. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology 83: 507–513.

- Lohmann K, Lohmann C (1996) Orientation and open-sea navigation in sea turtles. The Journal of Experimental Biology 199: 73–81.