Leatherback |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Dermochelydae | Dermochelys coriacea

English common names: Leatherback, Leatherback Sea Turtle.

Spanish common names: Laúd, tortuga laúd, tortuga baula, tortuga canal, tortuga cardón.

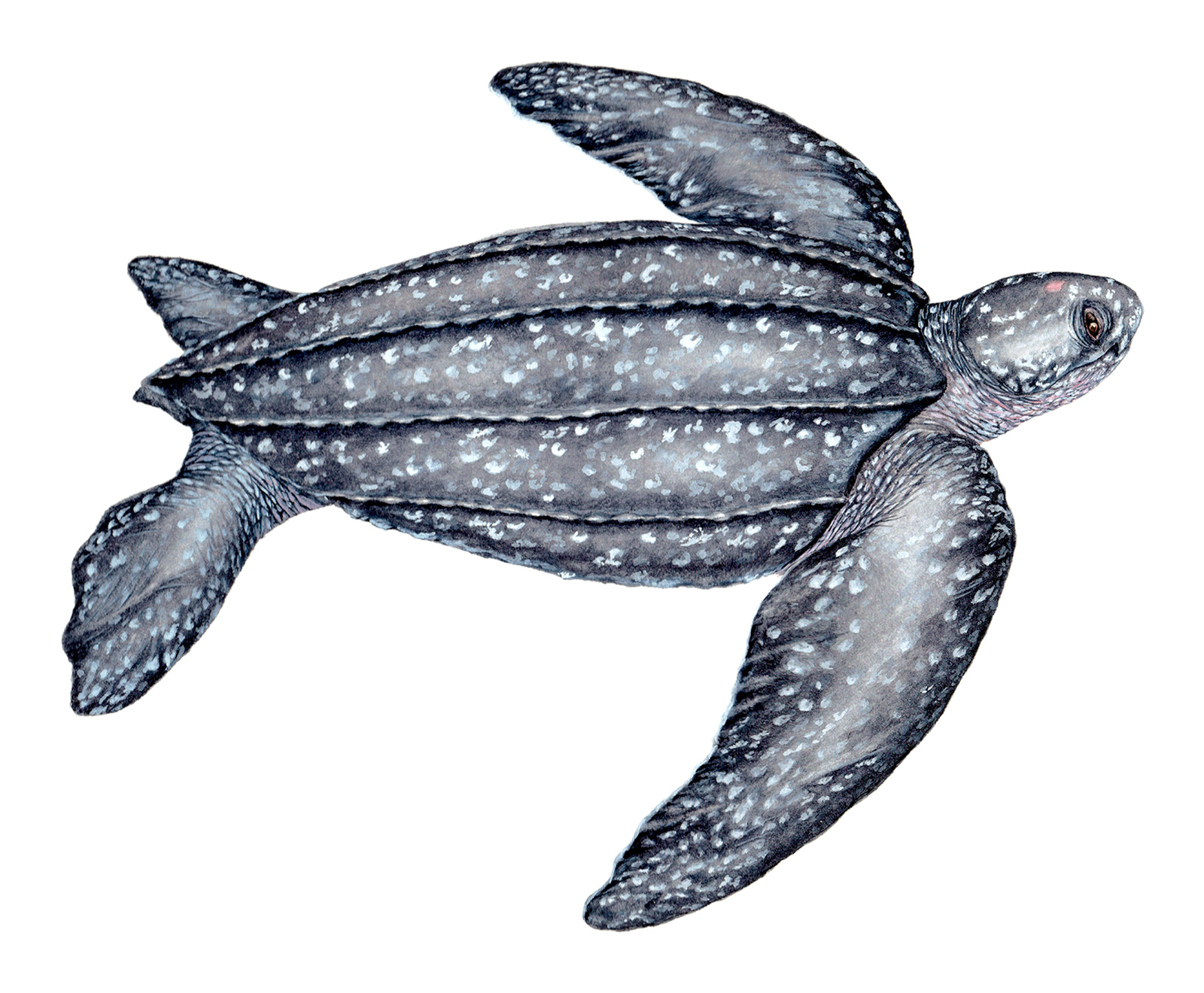

Recognition: ♂♂ 250.1 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 174.3 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace.. Dermochelys coriacea is the world's largest turtle. It is unique among sea turtles in having a lyre-shaped leathery carapace with seven distinct longitudinal ridges. Unlike the carapace of the shelled sea turtles, which is covered by bony scutes, the carapace of the Leatherback Sea Turtle is formed by thick leathery skin and minute osteoderms (tiny bone plates). Although the largest specimen ever recorded is a male, usually both sexes are similar in body size. Males are distinguished by having longer tails where the cloaca reaches beyond the posterior edge of the carapace.1

Illustration. Adult female. | |

| |

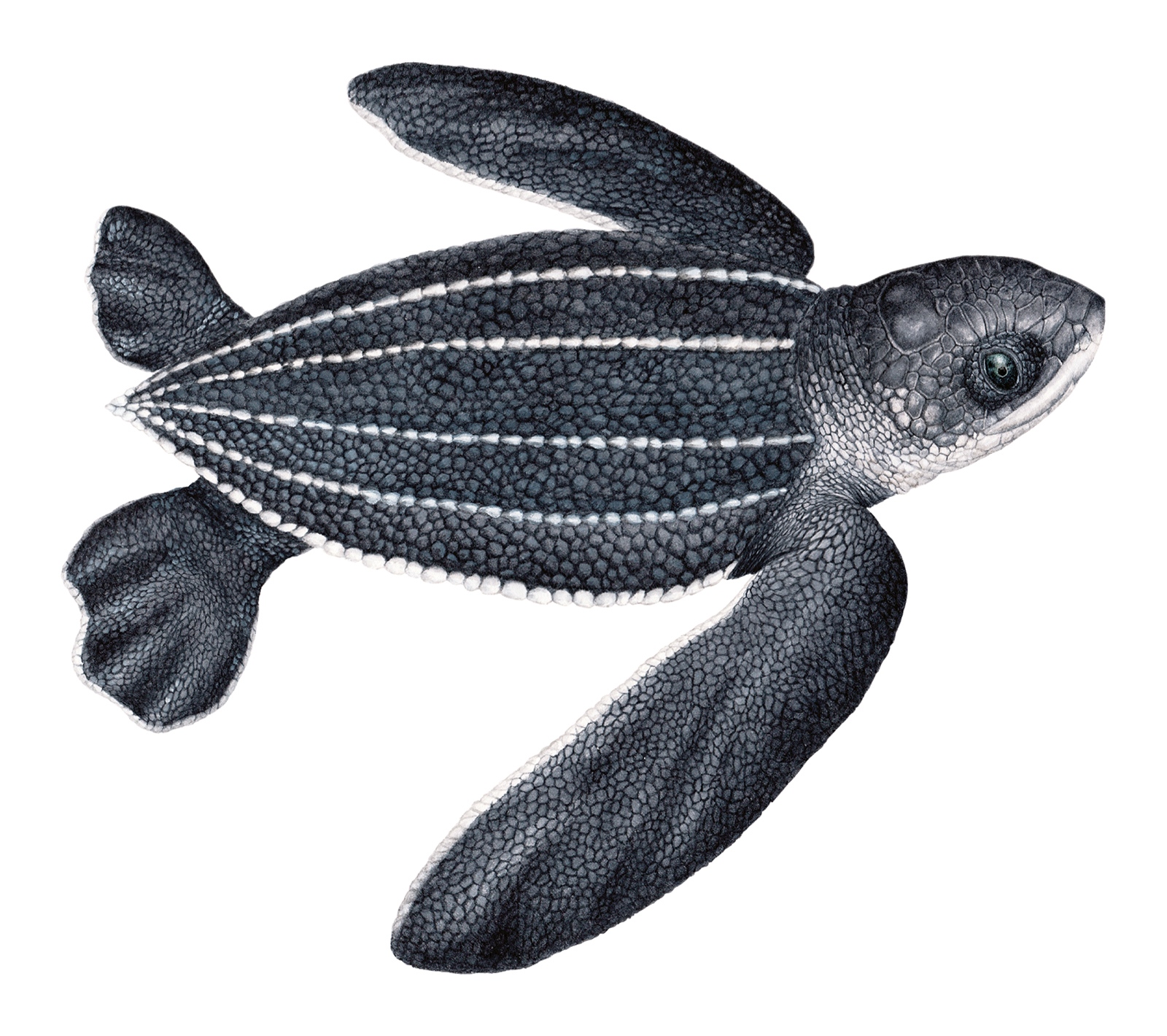

Illustration. Hatchling. | |

| |

Natural history: Extremely rare in Ecuadorian waters. After hatching on tropical and subtropical beaches,1 hatchlings of Dermochelys coriacea frantically swim for 1–3 days in an offshore direction2 until they reach open ocean "nursery" habitats in tropical (greater than 26°C) waters.3 Here, they spend 12–16 years2,4 drifting along with surface currents,5 as well as actively diving and foraging within 18 m from the surface.6 In nesting grounds throughout the world, hatchlings of D. coriacea are preyed upon by a variety of animals. Predators include mammals (such as pigs, dogs, honey badgers, polecats, mongooses, coatis, raccoons, civets, genets, and rats), birds (including eagles, caracaras, hawks, kites, herons, vultures, crows, frigate birds, gulls, and terns), monitor lizards, fish, and arthropods (including crabs, ants, and mole crickets).1,7

When they reach a carapace length of ~100 cm, juvenile Dermochelys coriacea move to cooler waters to take advantage of abundant and predictable prey resources.3,8 Throughout their life, Leatherbacks feed almost exclusively on jellyfish, salps, and other gelatinous organisms, but may as well ingest fish, crustaceans (such as amphipods and crabs), mollusks (including squid and snails), seagrasses, and algae.1,9 The gelatinous diet is energy-poor,10 so Leatherback Sea Turtles must ingest large quantities (up to 200 kg of jelly organisms, representing 26–73% of their body mass, daily).11–13 Individuals of D. coriacea feed throughout the water column, from the surface to great depth.9 They swim continuously throughout the day and night,14 and spend 74–91% of their time submerged,15 usually within 250 m from the surface but down to 1,230 m in depth16 and for up to 87 minutes.17

Adult Leatherbacks travel almost continuously throughout their lives,18 moving up to 70 km per day,19 both actively and passively along with major oceanic currents.19 In the open ocean, they orient themselves using geomagnetic cues.20,21 They forage over vast (up to 206,816 km2)22 stretches of open ocean and over continental shelves,23,24 or reside within smaller foraging areas close to shore,25 routinely migrating to distant (up to 20,558 km away)26 foraging grounds.8 Leatherback Sea Turtles also range into boreal (0.4°C) waters,27 where they maintain (by means of their large body mass, thick fatty insulation, and control of their swimming speed)28 their core body temperature up to 18°C above the water temperature.29

Individuals of Dermochelys coriacea become sexually mature at an age of 25–29 years.4 During breeding season, they gather in polygamous (females mate with more than one male and vice versa)30 rookeries in shallow waters usually close (within 100 km) to the nesting beaches.1 Copulation takes place on the water surface31 and may last for 7–10 hours.32 Females of D. coriacea are capable of storing sperm during the breeding season,30 and the majority (84–100%) of their clutches are sired by only one male.33 Females nest every 1–9 years1,34 on roughly (6.4 m to 3.2 km apart)35,36 the same beaches (which may also be the same on which they themselves hatched),37 but may sometimes select different beaches up to 140 km apart.38

The nesting season of the Leatherback Sea Turtle generally coincides with summer at times of plentiful rainfall,1 but nesting is extremely rare in Ecuador.39 During a single season, females of D. coriacea may lay 1–13 clutches1 at intervals of 7–15 (but often 9–10) days.1 They produce 20–160 eggs per clutch1 and lay them mostly soft-sand beaches1 in 37–119 cm deep nests,40 usually in the open.36,41 During nesting emergences, which last 80–140 minutes1 and take place mostly at night1 or at sunset within a few hours of the high tide,42 female Leatherback Sea Turtles are very shy, and can easily be scared back into the sea.42 Nesting is mostly solitary,39 but occasionally in aggregations, with up to 97 females nesting in a single stretch (1 km long) of beach per night.43

The incubation period of the Leatherback Sea Turtle's eggs is 54–93 days,35,44 and ~50% (0–80%) of the eggs hatch.1,45 Temperature determines the sex of the offspring,46 and the proportion of female hatchlings increases with the incubation temperature.47 Nest temperatures >29.75ºC produce females and temperatures <28.75ºC generate males.48 Throughout the world, eggs of Dermochelys coriacea are preyed upon by a variety of mammals (including pigs, dogs, jackals, honey badgers, mongooses, coatis, raccoons, civets, opossums, drills, and porcupines), birds (such as vultures and crows), monitor lizards, and arthropods (including crabs, fly larvae, ants, locust larvae, and mole crickets).1,7 They are also occasionally lost to erosion,1,7 inundation,49 elevated sand temperatures,50 trampling by cattle,1 in addition to being widely used for human consumption.1 The eggs of D. coriacea hatch synchronously and usually at night.1 Some hatchlings are unable to dig their way out of the nest, and perish.1 During nocturnal emergence, the presence of artificial lighting affects the orientation of hatchlings,7 which may result in mortality caused by traffic, dehydration, exhaustion, or predation.1 During diurnal emergence, desiccation causes hatchling mortality.1 From the surviving stock, it is estimated that less than 0.1% reach adulthood.51

Jaguars, tigers, and crocodiles prey upon female Leatherback Sea Turtles during nesting emergences,1 whereas killer whales and sharks prey on the turtles in the open ocean.1 Other causes of mortality for adult Leatherbacks include heat exhaustion during diurnal nesting emergences, ingestion of plastic and crude oil, collision with boats, interactions with fishing gear, and direct harvesting for oil and food (although their meat may cause food poisoning).1,7,52 Individuals of Dermochelys coriacea are parasitized by a variety of worms, and colonized by fish, barnacles, and isopods.1 Based on adult D. coriacea growth rates,4,53 we estimate the maximum lifespan of this species to be at least 83 years.

Conservation: Vulnerable.54 Dermochelys coriacea is listed in this category because its populations have declined 40% over the past three generations as a result of incidental mortality due to interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.54 Another threat faced by D. coriacea is the increase of the average global temperature, which not only may result in the complete feminization of some populations,47,55,56 but also in large-scale mortality of embryos due to lethal field temperatures.50 Under some scenarios of global sea level rise,57 up to 32% of the area of some D. coriacea nesting beaches may be lost by 2100.

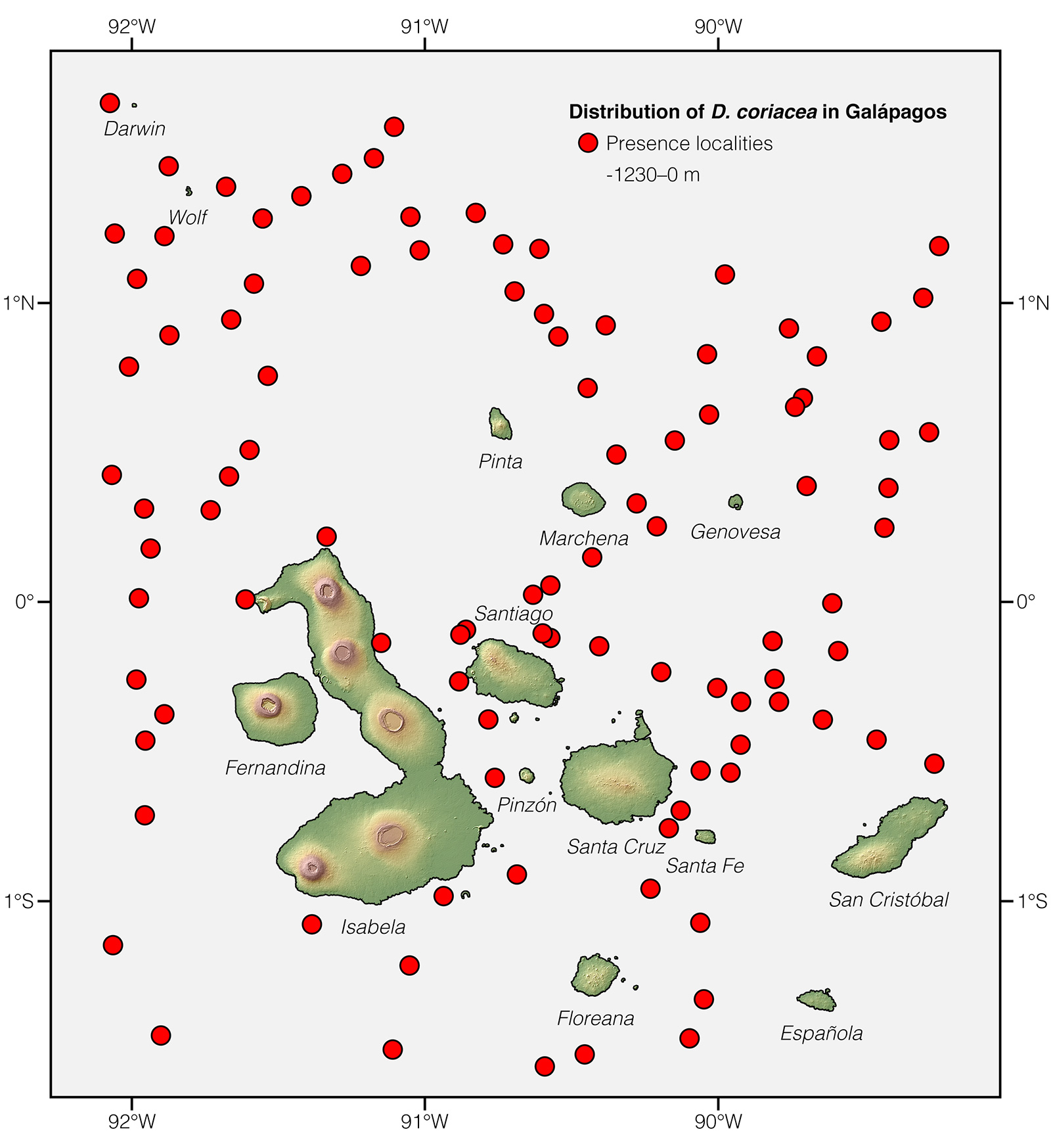

Unlike the population of Leatherback Sea Turtles in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, which is large (estimated at 50,842 individuals in 2010) and increasing, the population on the eastern Pacific has precipitously declined from an estimated 35,356 before human impact to just 926 (a >97% decline) in 2010.54 Leatherbacks transiting through Galápagos waters belong to this subpopulation and they face the threat of chronic mortality due to incidental catch in fishing gear when migrating from Central American nesting grounds, especially between April and June.58 Before arriving in Galápagos, the turtles have to go through a "minefield" having nearly 40,000 longline fishing hooks.58

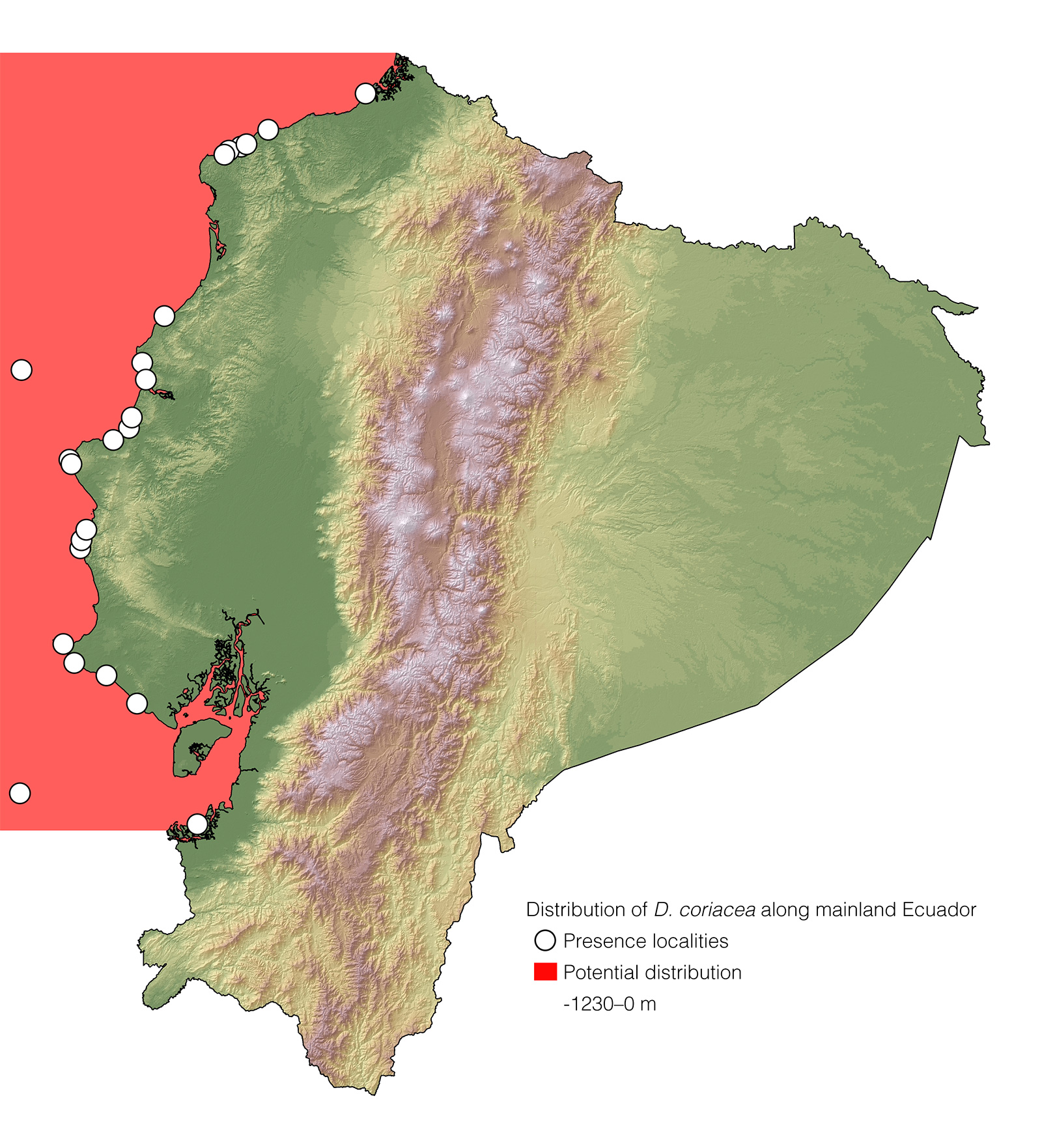

Distribution: Dermochelys coriacea is the most widely distributed reptile species. It occurs on tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal waters worldwide.1

Etymology: The generic name Dermochelys, which comes from the Greek words derma (meaning “skin”) and chelys (meaning “turtle”),59 refers to the coarse skin covering the carapace. The specific epithet coriacea comes from the Latin word coriaceus (meaning “leathery”)59 and is a reference to the turtle's carapace skin texture.

See it in the wild: Dermochelys coriacea cannot be expected to be seen reliably along the coast of mainland Ecuador and Galápagos, since individuals transiting through the country's waters are rarely spotted, and only a few records of nesting females exist on Ecuadorian beaches.

Special thanks to Kay for symbolically adopting the Leatherback Sea Turtle and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Juan José Alava.

Illustrator. Valentina Nieto Fernández.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Dermochelys coriacea. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

FAQ

Do Leatherback Sea Turtles get high eating jellyfish? Although jellyfish have the potential to affect the physiology of their predators owing to the toxicity of their specialized stinging cells, it is unlikely that they are capable of causing a Leatherback Sea Turtle to "get high." Leatherbacks are continuously eating jellyfish throughout their lives, and they need large quantities (26–73% of their body mass, daily)11–13 just to meet their daily energy requirements.

Do Leatherback Turtles have teeth? Leatherback Turtles do not have teeth. Instead, they have hundreds of backward-pointing spines throughout their esophagous. These teeth-like projections prevent the turtle's gelatinous prey from floating back out.

How can you help Leatherback Sea Turtles? The best way you can help ensure a future for Leatherback Sea Turtles is by supporting or volunteering at conservation organizations such as Sea Turtle Conservancy.

How do Leatherback Sea Turtles communicate? Leatherback Sea Turtle embryos and hatchlings are capable of emitting sounds which presumably play an important role in communication within the group.60 It is likely that adult Leatherbacks communicate in a similar way, as they are capable of producing sounds,61 and other sea turtle species are capable of perceiving underwater low frequency sounds.62

How fast do Leatherback Turtles swim? Leatherback Sea Turtles swim faster than humans, up to 10.1 km/h.14 Michael Phelps’ top swimming speed is 9.7 km/h.

How many Leatherback Sea Turtles are there left? The most recent published conservation assessment54 of Leatherbacks estimates their global population to be 90,559 individuals.

What is the biggest sea turtle ever recorded? Leatherback Sea Turtles are the largest living turtles. The biggest Leatherback Sea Turtle ever recorded for which there is published63 evidence was a male measuring 250.1 cm (slightly over 2.5 meters or 8.2 feet) and having a weight of 916 kg, found dead on Wales, 1988.

When do Leatherback Turtles sleep? One of the most startling characteristics of the biology of Leatherback Sea Turtles is that they swim continuously throughout their lives, with little or no resting.14 Since they rarely stop moving, surface resting must not occur.

Where can I see Leatherback Turtles? The best places to see Leatherback Turtles are its largest colonies, which are located in French Guiana, Surinam, and Trinidad and Tobago.1

Where do Leatherback Sea Turtles live? The Leatherback Sea Turtle is the most widely distributed reptile species. It occurs on tropical, subtropical, temperate, and boreal waters worldwide.1

Why are Leatherback Turtles going extinct? Leatherback Sea Turtles are going extinct because their populations have declined 40% over the past three generations as a result of incidental mortality due to interactions with fisheries, direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.54

Literature cited:

- Eckert KL, Wallace BP, Frazier JG, Eckert SA, Pritchard PCH (2012) Synopsis of the biological data on the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). U.S. Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, D.C., 159 pp.

- Boyle MC (2006) Post-hatchling sea turtle biology. PhD thesis, Townsville, Australia, James Cook University.

- Eckert SA (2002) Distribution of juvenile leatherback sea turtle Dermochelys coriacea sightings. Marine Ecology Progress Series 230: 289–293.

- Avens L, Taylor JC, Goshe LR, Jones TT, Hastings M (2009) Use of skeletochronological analysis to estimate age of leatherback sea turtles Dermochelys coriacea in the western north Atlantic. Endangered Species Research 8: 165–177.

- Gaspar P, Benson SR, Dutton PH, Réveillère A, Jacob G, Meetoo C, Dehecq A, Fossette S (2012) Oceanic dispersal of juvenile leatherback turtles: going beyond passive drift modeling. Marine Ecology Progress Series 457: 265–284.

- Salmon M, Jones TT, Horch KW (2004) Ontogeny of diving and feeding behavior in juvenile seaturtles: leatherback seaturtles (Dermochelys coriacea L) and green seaturtles (Chelonia mydas L) in the Florida Current. Journal of Herpetology 38: 36–43.

- NOAA (2013) Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, 89 pp.

- James MC, Sherrill-Mix SA, Martin K, Myers RA (2006) Canadian waters provide critical foraging habitat for leatherback sea turtles. Biological Conservation 133: 347–357.

- Bjorndal KA (1997) Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles. In: Musick JA, Lutz PL (Eds) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 199–231.

- Davenport J (2017) Crying a river: how much salt-laden jelly can a leatherback turtle really eat? The Journal of Experimental Biology 220: 1737–1744.

- Duron-Dufrenne M (1987) Premier suivi par satellite en Atlantique d’une tortue luth Dermochelys coriacea. Comptes Rendus Academie des Sciences Paris 304: 339–402.

- Jones TT, Bostrom BL, Hastings MD, Van Houtan KS, Pauly D, Jones DR (2012) Resources requirements of the Pacific leatherback turtle population. PLoS One 7: e45447.

- Heaslip SG, Iverson SJ, Bowen WD, James MC (2012) Jellyfish support high energy intake of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea): video evidence from animal-bourne cameras. PLoS ONE 7: e33259.

- Eckert SA (2002) Swim speed and movement patterns of gravid leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) at St Croix, US Virgin Islands. Journal of Experimental Biology 205: 3689–3697.

- Musick JA, Lutz PL (1997) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 446 pp.

- Hays GC, Houghton JDR, Myers AE (2004) Pan-Atlantic leatherback turtle movements. Nature 429: 522.

- López-Mendilaharsu M, Rocha CFD, Domingo A, Wallace BP, Miller P (2009) Prolonged deep dives by the leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea: pushing their aerobic dive limits. Marine Biodiversity Records 2: e35.

- Hays GC, Hobson VJ, Metcalfe JD, Righton D, Sims DW (2006) Flexible foraging movements of leatherback turtles across the North Atlantic Ocean. Ecology 87: 2647–2656.

- Fossette S, Hobson VJ, Girard C, Calmettes B, Gaspar P, Georges JY, Hays GC (2010) Spatio-temporal foraging patterns of a giant zooplanktivore, the leatherback turtle. Journal of Marine Systems 81: 225–234.

- Dodge KL, Galuardi B, Lutcavage ME (2015) Orientation behaviour of leatherback sea turtles within the North Atlantic subtropical gyre. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20143129.

- Lohmann KJ, Lohmann C (1993) A light-independent magnetic compass in the leatherback sea turtle. The Biological Bulletin 185: 149–151.

- Almeida AP, Eckert SA, Bruno SC, Scalfoni JT, Giffoni B, López-Mendilaharsu M, Thomé JCA (2011) Satellite-tracked movements of female Dermochelys coriacea from southeastern Brazil. Endangered Species Research 15: 77–86.

- James MC, Myers RA, Ottensmeyer CA (2005) Behaviour of leatherback sea turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, during the migratory cycle. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 272: 1547–1555.

- Benson SR, Eguchi T, Foley DG, Forney KA, Bailey H, Hitipeuw C, Samber BP, Tapilatu RF, Rei V, Ramohia P, Pita J, Dutton PH (2011) Large-scale movements and high-use areas of western Pacific leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea. Ecosphere 2: 84.

- Robinson NJ, Morreale SJ, Nel R, Paladino FV (2016) Coastal leatherback turtles reveal conservation hotspot. Scientific Reports 6: 37851.

- Benson SR, Dutton PH, Hitipeuw C, Samber B, Bakarbessy J, Parker D (2007) Post-nesting migrations of leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) from Jamursba-Medi, Bird’s Head Peninsula, Indonesia. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6: 150–154.

- James MC, Davenport J, Hays GC (2006) Expanded thermal niche for a diving vertebrate: a leatherback turtle diving into near-freezing water. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 335: 221–226.

- Bostrom BL, Jones DR (2007) Exercise warms adult leatherback turtles. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A 147: 323–331.

- Frair W, Ackman RG, Mrosovsky N (1972) Body temperature of Dermochelys coriacea: warm turtle from cold water. Science 177: 791–793.

- Pearse DE, Avise JC (2001) Turtle mating systems: behavior, sperm storage, and genetic paternity. Journal of Heredity 92: 206–211.

- Godfrey M, Barreto R (1998) Dermochelys coriacea (Leatherback sea turtle) copulation. Herpetological Review 29: 40–41.

- Baptiste SL, Sammy D (2007) Final report: basic course on community-based sea turtle ecotourism, tour guiding and management. WIDECAST, Roseau, 39 pp.

- Bowen BW, Karl SA (2007) Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Molecular Ecology 16: 4886–4907.

- Saba VS, Santidrián Tomillo P, Reina RD, Spotila JR, Musick JA, Evans DA, Paladino FV (2007) The effect of the El Niño Southern Oscillation on the reproductive frequency of eastern Pacific leatherback turtles. Journal of Applied Ecology 44: 395–404.

- Hernández R, Buitrago J, Guada H, Hernández-Hamón H, Llano M (2007) Nesting Distribution and hatching success of the leatherback, Dermochelys coriacea, in relation to human pressures at Playa Parguito, Margarita Island, Venezuela. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6: 79–86.

- Neeman N, Harrison E, Wehrtmann IS, Bolaños F (2015) Nest site selection by individual leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea, Testudines: Dermochelyidae) in Tortuguero, Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical 63: 491–500.

- Dutton DL, Dutton PH, Chaloupka M, Boulon RH (2005) Increase of a Caribbean leatherback turtle Dermochelys coriacea nesting population linked to long-term nest protection. Biological Conservation 126: 186–194.

- Stewart KR (2007) Establishment and growth of a sea turtle rookery: the population biology of the leatherback in Florida. PhD thesis, Durham, United States, Duke University.

- Chacón-Chaverri D (2004) Synopsis of the Leatherback Sea Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles, San José, 27 pp.

- Tapilatu RF, Tiwari M (2007) Leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, hatching success at Jamursba-Medi and Wermon beaches in Papua, Indonesia. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6: 154–158.

- Nordmoe ED, Sieg AE, Sotherland PR, Spotila JR, Paladino FV, Reina RD (2004) Nest site fidelity of leatherback turtles at Playa Grande, Costa Rica. Animal Behaviour 68: 387–394.

- Reina RD, Mayor PA, Spotila JR, Piedra R, Paladino FV (2002) Nesting ecology of the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea, at Parque Nacional Marino Las Baulas, Costa Rica: 1988–1989 to 1999–2000. Copeia 2002: 653–664.

- Rivalan P, Pradel RH, Choquet R, Girondot M, Prévot-Julliard A (2006) Estimating clutch frequency in the sea turtle Dermochelys coriacea using stopover duration. Marine Ecology Progress Series 317: 285–295.

- Limpus CJ, MacLachlin N (1979) Observations on the leatherback turtle, Dermochelys coriacea (L.), in Australia. Australian Wildlife Research 6: 105–116.

- Bell BA, Spotila JR, Paladino FV, Reina RD (2004) Low reproductive success of leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, is due to high embryonic mortality. Biological Conservation 115: 131–138.

- Mrosovsky N (1994) Sex ratios of sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270: 16–27.

- Santidrián Tomillo P, Oro D, Paladino FV, Piedra R, Sieg AE, Spotila JR (2014) High beach temperatures increased female-biased primary sex ratios but reduced output of female hatchlings in the leatherback turtle. Biological Conservation 176: 71–79.

- Mrosovsky N, Fretey J, Lescure J, Pieau C, Rimblot F (1985) Sexual differentiation as a function of the incubation temperature of eggs in the sea-turtle Dermochelys coriacea (Vandelli, 1761). Amphibia-Reptilia 6: 83–92.

- Hitipeuw C, Dutton PH, Benson S, Thebu J, Bakarbessy J (2007) Population status and internesting movement of leatherback turtles, Dermochelys coriacea, nesting on the Northwest Coast of Papua, Indonesia. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 6: 28–36.

- Santidrián Tomillo P, Saba VS, Blanco GS, Stock GA, Paladino FV, Spotila JR (2012) Climate driven egg and hatchling mortality threatens survival of Eastern Pacific leatherback turtles. PLoS ONE 7: e37602.

- Sandrillán Tomillo P (2007) Factors affecting population dynamics of eastern Pacific leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). PhD thesis, Philadelphia, United Sates, Drexel University.

- Orós J, Torrent A, Calabuig P, Déniz S (2005) Diseases and causes of mortality among sea turtles stranded in the Canary Islands, Spain (1998-2001). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 63: 13–24.

- Price ER, Wallace BP, Reina RD, Spotila JR, Paladino FV, Piedra R, Vélez E (2004) Size, growth, and reproductive output of adult female leatherback turtles Dermochelys coriacea. Endangered Species Research 5: 1–8.

- Wallace BP, Tiwari M, Girondot M (2013) Dermochelys coriacea. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Patino-Martinez J, Marco A, Quiñones L, Hawkes LA (2011) A potential tool to mitigate the impacts of climate change to the caribbean leatherback sea turtle. Global Change Biology 18: 401–411.

- Mrosovsky N, Dutton PH, Whitmore CP (1984) Sex ratios of two species of sea turtle nesting in Suriname. Canadian Journal of Zoology 62: 2227–2239.

- Fish MR, Cote IM, Gill JA, Jones AP, Renshoff S, Watkinson AR (2005) Predicting the impact of sea‐level rise on Caribbean Sea turtle nesting habitat. Conservation Biology 19: 482–491.

- Roe JH, Morreale SJ, Paladino FV, Shillinger GL, Benson SR, Eckert SA, Bailey H, Santidrián Tomillo P, Bograd SJ, Eguchi T, Dutton PH, Seminoff JA, Block BA, Spotila JR (2014) Predicting bycatch hotspots for endangered leatherback turtles on longlines in the Pacific Ocean. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281: 20132559.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Ferrara CR, Vogt RC, Harfush MR, Sousa-Lima RS, Albavera E, Tavera A (2014) First evidence of Leatherback Turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) embryos and hatchlings emitting sounds. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 13: 110–114.

- Cook SL, Forrest TG (2005) Sounds produced by nesting Leatherback Sea Turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Herpetological Review 36: 387–390.

- Bartol SM, Musick JA, Lenhardt ML (1999) Auditory evoked potentials of the loggerhead sea turtle. Copeia 1999: 836–840.

- Márquez R (1990) FAO species catalogue. Sea turtles of the world. FAO Fisheries Synopsis 11: 53–58.