Published January 17, 2021. Updated March 16, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Common Mussurana (Clelia clelia)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Clelia clelia

English common names: Common Mussurana, Black Mussurana, Black Cribo.

Spanish common names: Ratonera común, chonta, lisa (Ecuador); cazadora negra (Colombia); zopilota, víbora de sangre (Juvenile), tiznada (Costa Rica); ratonera (Venezuela).

Recognition: ♂♂ 180 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 260 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1 Clelia clelia is a large, robust snake with a cylindrical body and comparatively small eyes. The adults have a uniform glossy black or gray dorsum whereas young individuals measuring less than 60 cm in total length have a bright red dorsum with black scale tips, black head, and a cream or yellow nuchal collar followed by a black band (Fig. 1).2,3 Individuals 60–90 cm in length are dull reddish brown to brownish black with a faint nape band.2 The belly is always white but the dorsal coloration impinges the margins of the ventral scales.4 Clelia clelia is the only snake in Ecuador having this coloration and 19 rows of smooth scales at mid-body. This species differs from Drepanoides anomalus, Pseudoboa coronata, and C. equatoriana by having a greater number of dorsal scale rows at mid-body.5–8

Figure 1: Individuals of Clelia clelia from Ecuador: Tiyu Yaku, Napo province (); Río Bigai Reserve, Orellana province (); La Selva Lodge, Sucumbíos province (); Zumba–Pucubamba road, Zamora Chinchipe province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Clelia clelia is a terrestrial and nocturnal snake that inhabits a variety of ecosystems ranging from savannas to cloud forests.9–11 Mussuranas occur in old-growth forest, especially along bodies of water,7,9 as well as in heavily disturbed areas such as pastures, cultivated fields,12 yards, rural houses,13 and along roadsides.9,14 Most individuals are seen active at night on the soil, leaf-litter, grass, swamps, creeks, or on rocky stream beds,2,15 but in some cases, they have been spotted on tree branches up to 170 cm above the ground.5,16 During the daytime, most individuals remain hidden, but others can be seen crossing roads and trails.5,9 This snake feeds on other snakes, occasionally larger than itself.17 Prey include harmless snakes (Chironius fuscus, C. exoletus,18 Dipsas palmeri,19 Drymarchon corais,20 Erythrolamprus reginae,2 Helicops angulatus,21 Ninia hudsoni,22 Tantilla melanocephala, Xenodon rabdocephalus, X. severus,23 as well as members of its own species), boas (Boa constrictor),13,24 vipers (Bothriechis nigroadspersus,25 Bothrops asper,26 Lachesis muta, and Porthidium nasutum27),28 and coralsnakes (Micrurus obscurus).23 Despite being primarily ophiophagous, Common Mussuranas also include in their diet: lizards (such as Ameiva ameiva,2 Enyalioides heterolepis,9 and species of the genus Tupinambis), snake eggs, opossums,29 rodents,5 birds, small mammals, and snails.1,30 Individuals of C. clelia are active foragers, tracking prey by quickly flicking their tongues to detect their scent trail.9 The species is much appreciated by villagers because of its snake-eating habits.1 Although it has grooved rear fangs and venom glands, this species also constricts its prey.1,31 After striking it, the Mussurana subsequently launches the third of its body to surround the prey and then tightens it with body coils until the prey stops resisting.14 After that, it ingest the prey (dead or alive) head-first. This species has natural immunity to the venom of vipers.32,33 Individuals are mostly calm. When grabbed, they constrict their bodies and do not usually strike, but instead hide their head under body coils and deploy a cloacal discharge.7 In humans, the venom of C. clelia can produce localized swelling, hemorrhage, and even necrosis (death of tissues and cells).34

“The bright red juveniles of the two Costa Rican mussuranas are considered to be víboras de sangre (blood snakes) whose bite results in bleeding over the entire body surface and death. This in an unfounded belief lacking any element of fact.”

Jay M Savage, American herpetologist, 2002.

Females of Clelia clelia reach sexual maturity at 97.3 cm of snout-vent-length; males at 65 cm. During courtship, the female may respond aggressively at first and on occasion, can kill and eat the male.31 After a gestation period of 47 days,1 females lay 9–25 eggs1,14 that take 117–120 days to hatch.35 In natural conditions, these are laid during periods of high rainfall. Hatchlings measure 31–49 cm in total length at birth.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..36 Clelia clelia is listed in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas, presumed stable populations, and adaptability to human-modified environments.36 However, the decline in the abundance of prey, coupled with the destruction and fragmentation of forested environments throughout Central and South America can be a threat for the long-term of survival of the species.37 In a rainforest locality in Panamá, the occurrence rates of C. clelia have diminished in the period from 1997 to 2012,38 probably as a result of the diminished snake abundance caused by a corresponding loss of amphibians.38 Additionally, individuals of C. clelia are commonly found dead on the roads due vehicular traffic.39

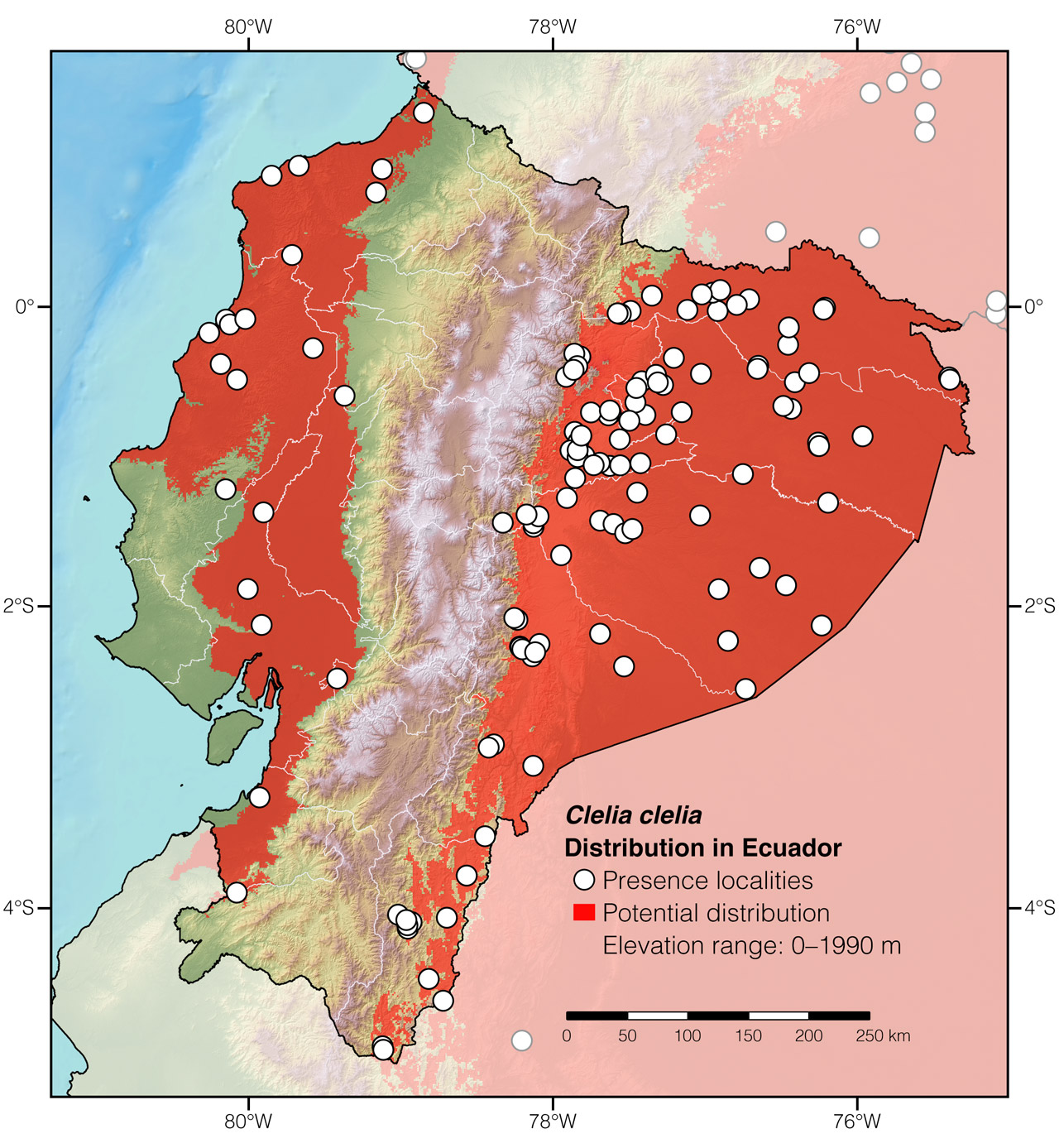

Distribution: Clelia clelia is widely-distributed in Central and South America, from southern México (Yucatán) to northern Argentina.11,36 The species has an estimated total range size of 2,078,373 km2 that encompasses much of Mesoamerica, the Chocó, Magdalena valley, the Llanos plains, the Amazon rainforest, and El Chaco.11 In Ecuador, this species occurs at both sides of the Andes (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Clelia clelia in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The word clelia is derived from the Latin Cloelia, a girl’s name meaning “illustrious” or “famous.” According to Roman legend, Cloelia was a heroine who was held hostage by an Etruscan invader. However, she managed to escape by swimming across the river Tiber.40

See it in the wild: Some of the best localities to find Common Mussuranas in the wild in Ecuador are Yasuní Scientific Station, Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, and Jama Coaque Reserve. The snakes are more easily located by walking along forested rivers and streams at night.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Darwin Núñez and Diego Piñán for providing locality data for Clelia clelia.

Authors: Juan C. Díaz-RicaurteaAffiliation: Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di DoménicodAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Díaz-Ricaurte JC, Arteaga A (2024) Common Mussurana (Clelia clelia). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/YKSW1188

Literature cited:

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Arquilla AM, Lehtinen RM (2018) Geographic variation in head band shape in juveniles of Clelia clelia (Colubridae). Mesoamerican Herpetology 5: 112–120.

- Murphy JC, Downie R, Smith JM, Livingstone S, Mohammed R, Lehtinen RM, Eyre M, Sewlal JN, Noriega N, Casper GS, Anton T, Rutherford MG, Braswell AL, Jowers MJ (2018) A field guide to the amphibians & reptiles of Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad and Tobago Naturalist’s Club, Port of Spain, 336 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- de Fraga R, Lima AP, da Costa Prudente AL, Magnusson WE (2013) Guia de cobras da região de Manaus - Amazônia Central. Editopa Inpa, Manaus, 303 pp.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- França FGR, Mesquita DO, Colli GR (2006) A checklist of snakes from Amazonian savannas in Brazil, housed in the Coleção Herpetológica da Universidade de Brasília, with new distribution records. Occasional Papers of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History 17: 1–13.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Lynch JD (2015) The role of plantations of the African palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in the conservation of snakes in Colombia. Caldasia 37: 169–182.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Leenders T (2019) Reptiles of Costa Rica: a field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 625 pp.

- Solórzano A (2004) Serpientes de Costa Rica. Distribución, taxonomía e historia natural. Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, 792 pp.

- Photographic record by César Barrio-Amorós.

- César Barrio-Amorós, pers. comm.

- Photo by Patrick Campbell.

- MECN, JOCOTOCO, ECOMINGA (2013) Herpetofauna en áreas prioritarias para la conservación: el sistema de reservas Jocotoco y Ecominga. Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales, Quito, 408 pp.

- Photo by Giuseppe Gagliardi-Urrutia.

- Photo by Vincent Vos.

- Wright T, Floyd E, Camper JD, Nilsson J (2019) Clelia clelia (Black Mussurana). Diet. Herpetological Review 50: 388–387.

- Harry Turner, pers. comm.

- Photo by Josua Hannink.

- Chavarría M, Barrio-Amorós C (2014) Clelia clelia. Predation. Mesoamerican Herpetology 1: 286.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Delia J (2009) Another crotaline snake prey item of the Neotropical snake Clelia clelia (Daudin 1983). Herpetology Notes 2: 21–22.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Martins Teixeira D, Lorini ML, Persson VG, Porto M (1991) Clelia clelia (Musurana). Feeding behavior. Herpetological Review 22: 131–132.

- Alencar LR, Gaiarsa MP, Martins M (2013) The evolution of diet and microhabitat use in Pseudoboine Snakes. South American Journal of Herpetology 8: 60–66. DOI: 10.2994/sajh-d-13-00005.1

- Scott Jr NJ (1983) Clelia clelia. In: Janzen DH (Ed) Costa Rican natural history. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 392–393.

- Cerdas L, Lomonte B (1982) Estudio de la capacidad ofiófaga y la resistencia de la zopilota (Clelia clelia, Colubridae) de Costa Rica a los venenos de serpiente. Toxicon 20: 936–939. DOI: 10.1016/0041-0101(82)90083-6

- Lomonte B, Cerdas L, Solórzano A, Martínez S (1989) El suero de neonatos de Clelia clelia (Serpentes: Colubridae) neutraliza la acción hemorrágica del veneno de Bothrops asper (Serpentes: Viperidae). Revista de Biología Tropical 38: 325–326.

- Weinstein SA, Warrell DA, White J, Keyler DE (2011) “Venomous” bites from non-venomous snakes. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 364 pp. DOI: 10.1016/C2010-0-68461-6

- Martínez S, Cerdas-Fallas L (1986) Captive reproduction of the Mussurana, Clelia clelia Daudin from Costa Rica. Herpetological Review 17: 12.

- Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Rivas G, Nogueira C, Gagliardi G, Catenazzi A, Gonzáles L, Murphy J (2019) Clelia clelia. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T197468A2487325.en

- Lynch JD (2012) El contexto de las serpientes de Colombia con un análisis de las amenazas contra su conservación. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 36: 435–449.

- Zipkin EF, DiRenzo GD, Ray JM, Rossman S, Lips KR (2020) Tropical snake diversity collapses after widespread amphibian loss. Science 367: 814–816. DOI: 10.1126/science.aay5733

- Vargas-Salinas F, Delgado-Ospina I, López-Aranda F (2011) Mortalidad por atropello vehicular y distribución de anfibios y reptiles en un bosque subandino en el occidente de Colombia. Caldasia 33: 121–138.

- Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011) The eponym dictionary of reptiles. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 296 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Clelia clelia in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Belén de Andaquíes | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Caserío La Rastra | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Morelia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Santuarios | Ruiz Valderrama 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda Fátima | Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Via antigua Caquetá–Huila | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Boca del Río Mira | Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Cabo Manglares | Higuera Rojas et al. 2021 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | La Paya | Peña Alzáte et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Piñuña, 22 km NE of | Hoyos et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Leguizamo, 25 km N of | Parques Nacionales de Colombia |

| Ecuador | Cañar | Terminal La Troncal | Ortega Torres 2015 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Machala | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Atacames | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Esmeraldas | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Pajonal | Morales 2004 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Palmicultora La Tolita | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Balzar | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Guayaquil | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Río Daule | MCZ 3570; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Bosque Petrificado Puyango | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Yangana | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Centro Científico Río Palenque | MCZ 152749; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Bosque Seco Lalo Loor | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Guayacán | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama Coaque Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Unión de Santa Ana | MHNG 2531.061; collection database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Maicito | MHNG 1357.014; collection database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Pedernales, 15 km SE of | Pazmiño-Otamendi 2020 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Jama | Photo by David Salazar |

| Ecuador | Manabí | San Isidro | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Bosque Protector Abanico | Cumba Endara 2008 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas, 14 km W of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Méndez–El Pescado road | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Normandía | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Quebrada Napinaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Reserva Ecológica El Paraíso | Photo by Alex Achig |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Santiago | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Upano | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Santa Ana, 1 km NE of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sardinayacu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Vall del Río Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona, 1.5 km N of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Baeza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | El Chaco | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | El Chaco, 1 km NE of | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Finca Fischer | TCWC 65016; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno Lodge | Photo by Margy Green |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guagua Sumaco | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guamaní | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hidroeléctrica Coca Codo Sinclair | MECN & ENTRIX 2009–2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ikiam | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | MCZ 173840; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Limoncocha | UIMNH 54662; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Bigai Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Rio Hollín | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Huataraco | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Oyacachi | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Quijos Ecolodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Suno | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Runa Huasi | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Francisco de Borja | USNM 210855; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena, 4 km N of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tiyu Yaku | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wildsumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Whitworth & Beirne 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zatzayacu, 4.5 km NNE | KU 146735; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zoo el Arca | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Ávila Viejo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo Apaika | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Cordillera Galeras | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dicaro, 1.8 km NW of | Photo by Morley Read |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Estación Científica Yasuní | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF, 5 km N of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Payamino, 6 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Payamino | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Orellana | SPF, 12 km N of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Maxus, km 98 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | USNM 210852 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Río Curaray | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Ecolodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Lago Gawope | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera, 3 km N of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Anzu Reserve | Reyes-Puig et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Punino | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | San José de Curaray | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Santa Ana | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Santa Clara | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Eno, 4.7 km N of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | MHNG 2445.005 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación Amazonas OCP | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación Cayagama | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE en Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lagartococha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | LACM 73327; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Mushullacta | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pisorié | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pozo Lago Norte | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Malo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Cerro Candelaria Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Reserva Río Zuñac | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alto Machinaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Cerro Plateado | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Ciudad Perdida | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Chorro, 1.4 km S of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Jamboé | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Jambué Bajo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Loja, 21 km E of | Zaher 1996 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Reserva Biológica Cerro Plateado | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Via Romerillos | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zumba–Pucubamba road | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Chiriaco, 43 km NE of | LSUMZ 39325; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Cumba | Koch et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Quebrada Honda | Koch et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Perico | Koch et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Loreto | Parinari | Nogueira et al. 2019 |