Published April 20, 2020. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Amazonian Bushmaster (Lachesis muta)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Lachesis muta

English common names: Amazonian Bushmaster, South American Bushmaster.

Spanish common names: Verrugosa amazónica, verrugosa del Oriente, motolo, yamunga (Ecuador); cascabel muda, cuaima, mapaná rayo, pudridora verrugosa, verrugoso (Colombia); shushupe, matabuey, cuanira, kempirona, macapé (Perú); cuaima piña (Venezuela); cascabel púa, pucarara, matacaballo (Bolivia); surucucu, surucutinga, pico-de-jaca, surucucu-pico-de-jaca (Brazil).

Recognition: ♂♂ 340 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 291 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. The Amazonian Bushmaster (Lachesis muta) is probably the longest venomous snake in the Americas, and the second in the world, after the King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah).1,2 The great majority of adults of L. muta measure less than 2.5 m, but some individuals measuring up to 4.5 m have been reported, but not confirmed.3 In the Ecuadorian Amazon, L. muta is identified from other vipers by having the following features: tail ending in a spine, prominent knoblike keels on the dorsal scales, which give the snake a “pineapple texture,” and a distinctive color pattern consisting of bold-black inverted triangles on a light brown ground dorsum (Fig. 1).2,4,5 Neonates (40–54.2 cm in total length)1,6 have a vibrant orangish dorsum and a yellowish tail.2 The most similar viper species that may be found living alongside L. muta in Ecuador is Bothrocophias microphthalmus, which is distinguished by having a dorsal pattern consisting of X-shaped markings on a brownish background.

Figure 1: Individuals of Lachesis muta from Llanganates National Park, Pastaza province, Ecuador.

Natural history: RareTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than ten. to extremely rareTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than three.. Lachesis muta is a nocturnal, solitary, and terrestrial viper that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen lowland and foothill forests, tropical dry forests and savannas (in Brazil),7 swamps,2 and plantations (of bamboo, banana, cacao, palm-oil, rubber, sugarcane, tea, or yucca).8–12 Occasionally, Amazonian Bushmasters venture into pastures,9 rural gardens, and houses.13,14 This species seems to prefer upland forest areas, but may as well occur in seasonally flooded forests during low-water season.2,15

Adult individuals of Lachesis muta spend most of their time (during the day as well as at night) coiled in ambush posture on the forest floor, either exposed or under herbaceous vegetation.13,16 They are also occasionally seen crawling on the forest floor,2 swimming across rivers,17 or crossing roads in the vicinity of forested areas.13,16 Juveniles dwell on leaf-litter, logs, buttress roots, and rocky areas.6 When not active, Amazonian Bushmasters hide under big rocks,18 under logs,16 in spiny palm scrub,19 or in any hole that fits the size and does not flood,18 particularly caves by armadillos, agoutis, and rabbits.13,18,20 Individuals may remain hidden in these lairs for days or even weeks.2

“Many people in parts of the southern Peruvian Amazon believe that the shushupe is a snake with the ability to transform into other animals, such as paca, agouti, or armadillo. The story is usually told in the setting of a hunter, on a walk at dawn or dusk, who has shot at one of these mammals. After the animal has been shot at but not killed, it usually retreats to a hole or den, close by. Not wanting to waste the animal, the hunters will dig up the burrow to find their meal but instead of finding it, they stumble across the shushupe. The hunters believe that the small mammal transformed into the dangerous snake for protection.”

“After hearing this story from many loggers and farmers, it became clear to me that the shushupe does not change form but in fact lives and coexists with these mammals. Keeping their dens clean from smaller, nuisance rodents.”

Harry Turner, English naturalist and explorer, 2020.

Individuals of Lachesis muta rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism. Unlike popular belief, they are not aggressive, but calm and sluggish when confronted by humans.9,14 In the presence of a disturbance, most individuals show no immediate defensive reaction, remaining coiled and immobile even when the vegetation around the snake is being cleared.13 If disturbed further, most Amazonian Bushmasters will flee, while others might emit a low whistle-like sound, vigorously wiggle the tail against the leaf-litter, or readily strike without a warning.8

In Ecuador and Peru, some indigenous groups (Achuar, Kichwa, Sápara, Shiwiar, and Shuar) associate the call of two species of Amazonian treefrogs (Tepuihyla tuberculosa and T. shushupe), with the “calling” of the Amazonian Bushmaster.9,21 The sound can be described as “an unearthly ascending series of kaks.”2 The origin of this association is unsure, since individuals of Lachesis muta cannot produce loud sounds.

South American Bushmasters are ambush predators. They sit-and-wait for prey to pass by, usually along small mammal pathways. Depending on the relative size of the prey, the snakes can “bite and hold” their prey or “bite and release,” subsequently following the scent trail of the envenomated prey.22 The diet of Lachesis muta is primarily based on small and medium-sized mammals such as rodents (rice rats, spiny rats, and agoutis),16,23,24 porcupines, squirrels, and opossums,2,25 but it also occasionally includes squirrel monkeys, frogs, and birds.26,27

Predators of Lachesis muta include snakes (Clelia clelia),28 peccaries,29 and humans.2 Indigenous communities in the Amazon consider Lachesis a delicacy, and there are records of bushmasters being cooked in villages in Peru2 and Venezuela.30 Individuals are often parasitized by tongue worms (Pentastomida) and lung worms (Rhabditida), which impairs respiration and may cause infected individuals to die from pneumonia.1

Lachesis muta is a venomous species (LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 2.8–9.75 mg/kg)31–33 that is responsible for 4.5–7.5% of snakebites throughout its range.2,14,34,35 In some areas, 17–35% of snakebites are attributed to this species, but these numbers almost surely correspond to misidentifications or exaggerations.14,36 Human envenomations by L. muta, although infrequent,36 can be severe due to the high amount of venom inoculated (up to 552 mg of dry venom per bite).37

“The Couni Couchi or Bushmaster is the most dreaded of all the South America serpents; and, as his name implies, he roams absolutely master of the forest. They do not fly from man, but will even pursue and attack him. They are fat, clumsy-looking animals, and nearly as thick as a man’s arm. They strike with immense force. So long are the fangs and so deep the wounds, that there is no hope of being cured.”

Sir Edward Sullivan, 1852.38

The venom of Lachesis is noteworthy because in addition to being hemorrhagic, necrotizing, myotoxic, and proteolytic, is also neurotoxic.36,39 Human victims of L. muta snakebite may experience agonizing local pain, swelling, bleeding, blistering, incoagulable blood, and necrosis (death of tissues and cells).14,31,40 Most victims also experience a syndrome usually not seen in those bitten by other viper species. This so-called “Lachesis Syndrome” includes nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, sweating, low blood pressure, impaired consciousness, faintness, respiratory distress, and shock.36

In poorly managed or untreated cases, envenomations by Lachesis muta can result in secondary infection, septicemia, shock, pulmonary edema, renal failure, amputations, permanent crippling deformity, disabilities, and (in 1.4% of cases)41 death in as little as 45 minutes.2,14,34,42 However, some bites to humans involve no envenomation at all (“dry bites”).43

What to do if you are bitten by a Amazonian Bushmaster?

|

Fortunately, the antivenom that is available in Ecuador, although produced based on individuals from other countries, can neutralize the venom of Lachesis muta.35,44 This is because the venom’s toxic and enzymatic activities are similar across Lachesis populations.44 Although serum therapy (antivenom) is the only recommended approach against a bite by an Amazonian Bushmaster, the fruit juice and the aqueous extract of leaves of soursop (Annona muricata) used by traditional “healers” may exert a protective action against the myotoxicity (muscle-breaking activity) of the venom.45

Breeding in Lachesis muta appears to be triggered by cold fronts and storms rather than correspond to a specific time of the year.6,46 During these times, males actively follow the pheromone trail of females.4,6 They also vigorously fight other males over access to females.1 During combats, males entwine their bodies with each other and try to push the opponent against the substrate.1 Courtship can last up to five hours and consists of the male rubbing its head and body, while flicking the tongue, over the female's body.4 Bushmasters are unique among New World vipers in that they lay eggs rather than give birth to live young.2,47 Females are capable of delaying fertilization by storing sperm for months.48 They deposit 3–23 eggs15,49,50 measuring 7–10 cm long50 in hollow logs or in mammal burrows.2,20

Unlike other South American vipers, females of Lachesis muta exhibit maternal care. They protect their clutch during the entirety of the incubation period, which is 60–95 days (~2–3 months).48,50 Considering the gestation plus incubation period, females can spend up to seven months without feeding.48 Hatchlings measure 40–54.2 cm in total length.1,6 Males become sexually mature when they reach ~122–129 cm in total length; females at ~112–164 cm, or in about 1–2 years.48,50,51 Under human care, individuals can live up to ~16 years,2 and probably much longer.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Lachesis muta is here proposed to be listed in this category because it is widely distributed,7 especially throughout the Amazon basin, a region that retains most of its original forest cover. Therefore, we consider that the species faces no major immediate extinction threats. We estimate that, in Ecuador, ~87.3% of the habitat of L. muta holds pristine forest. Unfortunately, the population of L. muta occurring on the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, which is genetically distinct,44 occurs over an area that has lost the majority (84–88.6%) of its forest cover,52 and is now largely restricted to forest fragments.53,54 Habitat destruction and consequent habitat fragmentation is the main threat to the long-term survival of the species.54 Other threats include traffic mortality,1,55,56 decline in small mammal populations, and direct killing.54

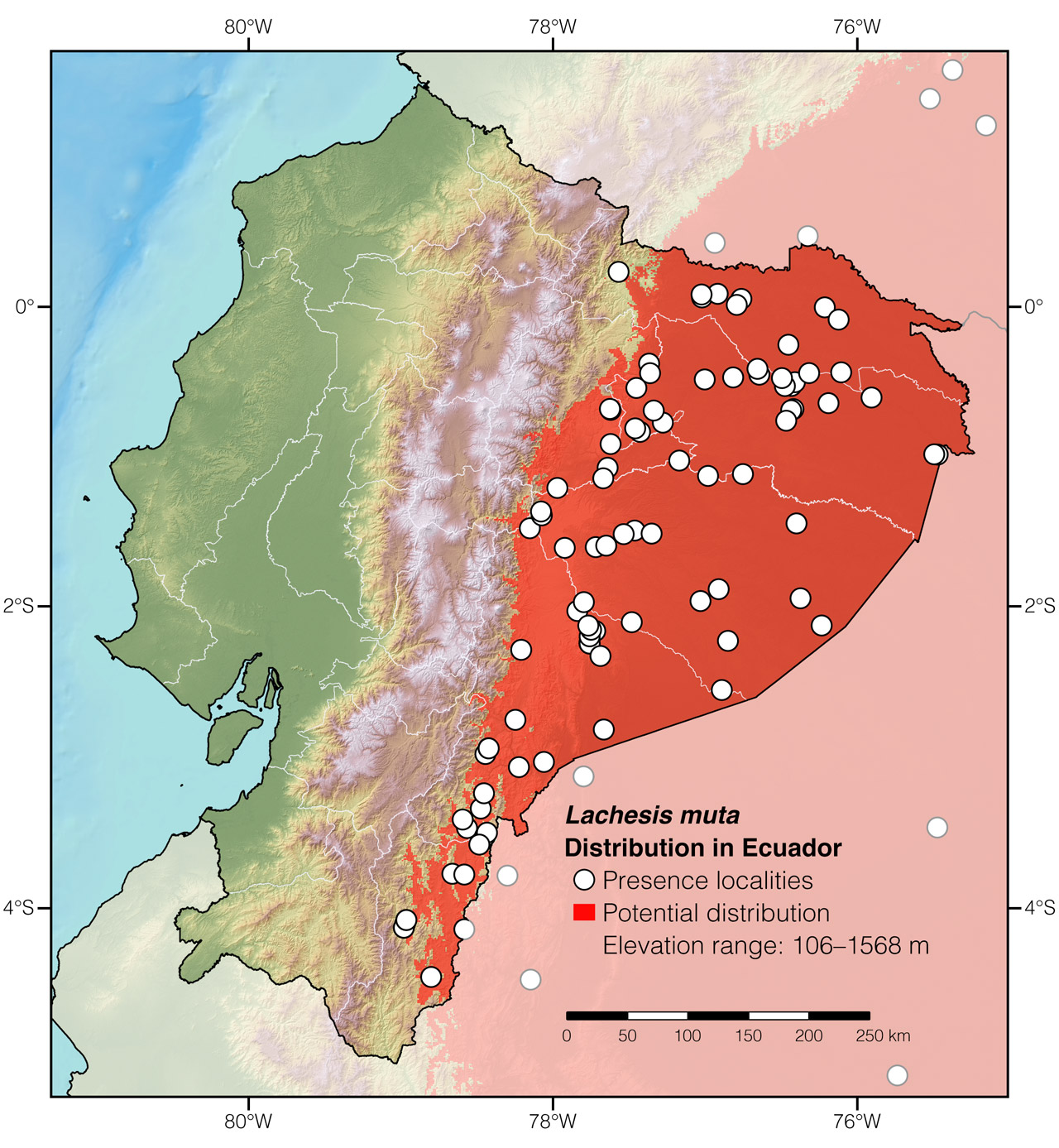

Distribution: Lachesis muta is native to an estimated ~5,489,350 km2 area throughout the Amazon basin and adjacent foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.7 It also occurs in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil.7 In Ecuador, the species occurs at elevations between 106 and 1568 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Lachesis muta in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Lachesis is derived from the name of one of the “Three Fates” (also known as Moirae or incarnations of destiny) in Greek mythology.2 Lachesis was the Moira that decided the length of life allotted to each human being and god.2 This epithet was probably given to reflect the feeling of having one’s fate at the mercy of the snake upon encountering such an imposing creature.57 The specific epithet muta is derived from the Latin word mutus (meaning “dumb” or “silent”).58 It refers the lack of a rattle, which is present in snakes of the closely related snake genus Crotalus.2

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Amazonian Bushmasters are recorded rarely, usually no more than once every few months at any given locality. However, in areas having unspoiled forest and low human population density, like in Yasuní Scientific Station and Bigal River Biological Reserve, individuals may be seen more frequently, albeit certainly not reliably. The snakes may be located by walking along trails or by cruising roads through primary forest.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS: |

How long is a bushmaster snake? Amazonian Bushmasters can grow up 3.4 m, which probably makes them the longest vipers in the world, and the second longest venomous snakes in the world, after the King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah).1,2 |

How venomous is the Amazonian Bushmaster? With a lethal dose of LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 2.8–9.75 mg/kg,31–33 the venom of the Amazonian Bushmaster is considered “extremely toxic.” In poorly managed or untreated human envenomations, the venom may cause renal failure, amputations, permanent crippling deformity, disabilities, and (in 1.4% of cases)41 death in as little as 45 minutes.2,14,34,42 |

Where are bushmasters snakes found? Bushmaster snakes occur in the tropical forests of Central American and northern South America.2 |

What does the Amazonian Bushmaster eat? Amazonian Bushmasters feed primarily on small and medium-sized mammals such as rodents (rice-rats, spiny rats, and agoutis),16,23,24 porcupines, squirrels, and opossums,2,25 but they also occasionally include squirrel monkeys, frogs, and birds in their diet.26,27 |

Will a bushmaster snake chase you? There are records of bushmaters actively, albeit slowly, pursuing people,1,5,38 but these instances probably correspond to snakes that mistake a warm foot or warm hand for food.2 |

Acknowledgments: The first author would like to thank Caroline Guevara-Molina for the comments and suggestions that enhanced the scientific quality of this work. Special thanks to Andreas Kay, Antonio Freire, Darwin Núñez, David Salazar, and Regdy Vera, for providing locality data for Lachesis muta. For providing natural history data, we are particularly grateful to Darwin Núñez, Ernesto Arbeláez, Harry Turner, and Konrad Mebert. The second author would like to thank Christopher Gillette for providing an image of an Amazonian Bushmaster preying upon a rice rat.

Special thanks to Grégoire Meier and Randers Regnskovs Naturfond for symbolically adopting the Amazonian Bushmaster and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Juan C. Díaz-Ricaurte,aAffiliation: Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. Alejandro Arteaga,bAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasamincAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Díaz-Ricaurte JC, Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Amazonian Bushmaster (Lachesis muta). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/BJCI8462

Literature cited:

- Ripa D (2002) The bushmasters: morphology in evolution and behavior. Cape Fear Serpentarium, Wilmington, 349 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Hoge AR, Lancini AR (1962) Sinopsis de las serpientes venenosas de Venezuela. Publicaciones Ocasionales del Museo de Ciencias Naturales 1: 1–24.

- Díaz-Ricaurte JC, Guevara-Molina SC, Cubides-Cubillos SD (2017) Lachesis muta (Linnaeus 1766). Catálogo de Anfibios y Reptiles de Colombia 3: 20–24.

- Beebe W (1918) Jungle Peace. Henry Holton and Company, New York, 297 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.20770

- Corrales G, Gómez A, Flores DA (2016) Reproduction of the South American Bushmaster, Lachesis muta (Serpentes: Viperidae), in captivity. Herpetological Review 47: 608–611.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Mellor NH, Arvin JC (1996) A bushmaster bite during a birding expedition in lowland southeastern Peru. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 3: 236–240. DOI: 10.1580/1080-6032(1996)007[0236:abbdab]2.3.co;2

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photographic record by Jacob Loyacano.

- Fuly AL, Machado AL, Castro P, Abrahao A, Redner P, Lopes UG, Guimaraes JA, Koatz VL (2007) Lysophosphatidylcholine produced by the phospholipase A2 isolated from Lachesis muta snake venom modulates natural killer activity as a protein kinase C effector. Toxicon 50: 400–410. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.04.008

- de Souza RCG (2007) A rare accident. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 42: 161–163.

- Argolo AJS (2003) Lachesis muta rhombeata Wied, 1825 (Serpentes, Viperidae): defensive behavior and snakebite risk. Herpetological Review 34: 210–211.

- Warrell DA (2004) Snakebites in Central and South America: epidemiology, clinical features, and clinical management. In: Campbell JA, Lamar WW (Eds) The Venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 709–761.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Darwin Núñez, pers. comm.

- César Barrio-Amorós, pers. comm.

- Konrad Mebert, pers. comm.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Mole RR (1924) The Trinidad Snakes. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1: 235–278. DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1924.tb01500.x

- Ron SR, Venegas PJ, Ortega-Andrade HM, Gagliardi-Urrutia G, Salerno PE (2016) Systematics of Ecnomiohyla tuberculosa with the description of a new species and comments on the taxonomy of Trachycephalus typhonius (Anura, Hylidae). Zookeys 630: 115–154. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.630.9298

- Boyer DM, Garrett CM, Murphy JB, Smith HM, Chiszar D (1995) In the footsteps of Charles C. Carpenter: facultative strike-induced chemosensory searching and trail-following behavior of bushmasters (Lachesis muta) at Dallas Zoo. Herpetological Monographs 9: 161–168. DOI: 10.2307/1467003

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Franchette JL, Sieing KE, Boinski S (2014) Social and personal information use by squirrel monkeys in assessing predation risk. American Journal of Primatology 76: 956–966. DOI: 10.1002/ajp.22283

- Carrillo de Espinosa N (1983) Contribución al conocimiento de las serpientes venenosas del Perú de las familias Viperidae, Elapidae, e Hydrophiidae (Ophidia: Reptilia). Publicaciones del Museo de Historia Natural “Javier Prado,” Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Serie Zoología 30: 1–55.

- Regdy Vera, pers. comm.

- Sasa M, Wasko DK, Lamar WW (2009) Natural history of the Terciopelo Bothrops asper (Serpentes: Viperidae) in Costa Rica. Toxicon 54: 904–922. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.06.024

- Photographic record by César Barrio-Amorós.

- Otero R, Furtado MFD, Gonçalves LR, Núñez V, García ME, Osorio RG, Romero M, Gutiérrez JM (1998) Comparative study of the venoms of three subspecies of Lachesis muta (bushmaster) from Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica. Toxicon 36: 2021–2027. DOI: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00089-0

- Sanchez EF, Freitas TV, Ferreira-Alves DL, Velarde DT, Diniz MR, Cordeiro MN, Agostini-Cotta G, Diniz CR (1992) Biological activities of venoms from South American snakes. Toxicon 30: 95–103. DOI: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90505-Y

- Terán MC, Lomonte B (2016) Actividad letal de seis venenos de serpientes de importancia médica en el Ecuador. Revista Ecuatoriana de Medicina y Ciencias Biológicas 37: 25–30. DOI: 10.26807/remcb.v37i2.4

- Magalhaes SFV, Peixoto HM, Moura N, Monteiro WM, de Oliveira MRF (2019) Snakebite envenomation in the Brazilian Amazon: a descriptive study. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 113: 143–151. DOI: 10.1093/trstmh/try121

- Smalligan R, Cole J, Brito N, Laing GD, Mertz BL, Manock S, Maudlin J, Quist B, Holland G, Nelson S, Lalloo DG, Rivadeneira G, Barragán ME, Dolley D, Eddleston M, Warrell DA, Theakston RDG (2004) Crotaline snake bite in the Ecuadorian Amazon: randomised double blind comparative trial of three South American polyspecific antivenoms. BMJ 329: 1129–1135. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1129

- Jorge MT, Sano-Martins IS, Tomy SC, Castro SCB, Ferrari RA, Ribeiro LA, Warrell DA (1997) Snakebite by the bushmaster (Lachesis muta) in Brazil: case report and review of the literature. Toxicon 35: 545–554. DOI: 10.1016/S0041-0101(96)00142-0

- Málaque CMS, França FOS (2015) Acidente laquético. In: Cardoso JLC, França FOS, Wen FH, Málaque CMS, Haddad Jr. V (Eds) Animais peçonhentos no Brasil: biologia, clínica e terapêutica dos acidentes. Editora Sarvier, São Paulo, 87–90.

- Hopley CC (1882) Snakes: curiosities and wonders of serpent life. Morrison & Gibb, Edinburgh, 614 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.7535

- Junqueira-de-Azevedo IL, Ching AT, Carvalho E, Faria F, Nishiyama MY, Jr., Ho PL, Diniz MR (2006) Lachesis muta (Viperidae) cDNAs reveal diverging pit viper molecules and scaffolds typical of cobra (Elapidae) venoms: implications for snake toxin repertoire evolution. Genetics 173: 877–889. DOI: 10.1534/genetics.106.056515

- Silva Haad J (1982) Accidentes humanos por las serpientes de los géneros Bothrops y Lachesis. Memórias do Instituto Butantan 44: 403–423.

- Hardy, DL (1995) Venomous snakes of Costa Rica: comments on feeding, behavior, venom, and human envenoming. Part II. Sonoran Herpetologist 8: 2–5.

- Magalhães O (1958) Campanha antiofídica em Minas Gerais. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 56: 291–371. DOI: 10.1590/S0074-02761958000200001

- Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm.

- Pla D, Sanz L, Molina-Sanchez P, Zorita V, Madrigal M, Flores-Diaz M, Alape-Giron A, Nunez V, Andres V, Gutierrez JM, Calvete JJ (2013) Snake venomics of Lachesis muta rhombeata and genus-wide antivenomics assessment of the paraspecific immunoreactivity of two antivenoms evidence the high compositional and immunological conservation across Lachesis. Journal of Proteomics 89: 112–123. DOI: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.05.028

- Cremonez CM, Leite FP, Bordon Kde C, Cerni FA, Cardoso IA, Gregorio ZM, de Souza RC, de Souza AM, Arantes EC (2016) Experimental Lachesis muta rhombeata envenomation and effects of soursop (Annona muricata) as natural antivenom. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases 22: 12. DOI: 10.1186/S40409-016-0067-6

- Souza R (2007) Reproduction of the Atlantic bushmaster (Lachesis muta rhombeata) for the first time in captivity. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 42: 41–43.

- Amaral A (1925) On the oviparity of Lachesis muta Daudin, 1803. Copeia 1925: 93–94. DOI: 10.2307/1435593

- Souza ED (2020) Biologia reprodutiva da surucucu-pico-de-jaca (Lachesis muta): de Norte a Nordeste do Brasil. MSc thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, 142 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Alves FQ, Argôlo AJS, Carvalho GC (2014) Reproductive biology of the bushmaster Lachesis muta (Serpentes: Viperidae) in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Phyllomedusa 13: 99–109. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v13i2p99-109

- Boyer DM, Mitchell LA, Murphy JB (1989) Reproduction and husbandry of the Bushmaster Lachesis m. muta at the Dallas Zoo. International Zoo Yearbook 28: 190–194. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-1090.1989.tb03279.x

- Ribeiro MC, Metzger JP, Martensen AC, Ponzoni FJ, Hirota MM (2009) The Brazilian Atlantic Forest: how much is left, and how is the remaining forest distributed? Implications for conservation. Biological Conservation 142: 1141–1153. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2009.02.021

- Rodrigues R, Albuquerque R, Santana D, Laranjeiras DO, Protázio A, França FGR, Mesquita D (2013) Record of the occurrence of Lachesis muta (Serpentes, Viperidae) in an Atlantic Forest fragment in Paraíba, Brazil, with comments on the species’ preservation status. Biotemas 26: 283–286. DOI: 10.5007/2175-7925.2013v26n2p283

- Pereira Filho GA, Sousa S, Sousa A, Barbosa A, França F, Freitas M (2020) The distribution of Lachesis muta (Linnaeus, 1766) in the Atlantic Forest of the Pernambuco Endemism Center, Northeastern Brazil. Herpetology Notes 13: 565–569.

- Hartmann PA, Hartmann MT, Martins M (2011) Snake road mortality in a protected area in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil. South American Journal of Herpetology 36: 35–42. DOI: 10.2994/057.006.0105

- Bennet AF (1991) Roads, roadsides and wildlife conservation: a review. In: Saunders DA, Hobbs RJ (Eds) Nature conservation 2: the role of corridors. Surrey Beatty and Sons Pty Ltd, Chipping Norton, 99–118.

- Diniz-Sousa R, Moraes JN, Rodrigues-da-Silva TM, Oliveira CS, Caldeira CAS (2020) A brief review on the natural history, venomics and the medical importance of bushmaster (Lachesis) pit viper snakes. Toxicon 7: 1–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxcx.2020.100053

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Lachesis muta in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Bocana Camicaya | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | La Floresta | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | La Paz | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Paujiles | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Pore | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | San Isidro | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Santa Fe | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Bloque 24 | Chávez 2016 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | La Hormiga | Díaz-Ricaurte et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Below Alshi | MAE Morona Santiago |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Bomboiza | Terán & Lomonte 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Chuwints | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kenkuim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kiim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chuwints | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cueva de los Tayos | DHMECN 64 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | El Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | El Tiink | This work |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Fauna de la Amazonía | Andreas Kay, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | Antonio Freire, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Kankaim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Limón | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Makuma | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mutintz | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Nunkandai | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Quebrada Río Napinaza | David Salazar, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Reserva el Quimi | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Carlos de Limón | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Karlos | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tunants | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Wisui | Chaparro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Yukaip | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Photo record by Peter Horrell |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huataraco | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha | Vigle 2008 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Pusuno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Jose de Dahuano | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Shiguancocha | Photo record by Fausto Gómez |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco | Camper et al. (in press) |

| Ecuador | Orellana | 130 km S Tiguino | USNM 321138 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bloque 31 | Libro PetroAmazonas |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bodega NPW | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | MHNG 2410.043 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Cotapino | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF–Tivacuno, km 7 1/2 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Parcela 50 ha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pompeya Sur | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal | Photo record by Thierry García |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San Jose de Mote | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Photo record by Fernando Vaca |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tambococha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur-Iro, km 58 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | W Puerto Ventura | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Waimo of Conoco | Zamudio & Greene 1997 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Copataza (Achuar) | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Intersección Cueva de los Tayos | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kurintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Latasas–Umupi | Morillo-Tobar 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Paparawua | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Peter Archer's place | Photo record by Peter Archer |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Piatúa | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Chambira | AMNH 49135 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pucayacu | USNM 165010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | AMNH 82006 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay | Photo record by Vincent Premel |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tzarentza | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Baboroé | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Batallón de Selva 56 | Photo record by Guido Bladimir |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | UF 30615 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pisorié | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Reserva Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | MECN 65 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shishicho | Pitman et al. 2002 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Bombuscaro | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Los Encuentros | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Parque Nacional Podocarpus 1 | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Parque Nacional Podocarpus 2 | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Pindal–Machinaza | MZUTI 5501 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Sendero Ciudad Perdida | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tundayme | This work |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Perú | Amazonas | Alto Cenepa | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Amazonas | Chosica | Consorcio AGUA SELVA 2014 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Cordillera del Cóndor | RAP 1994 |

| Perú | Loreto | Alto Cahuapanas | Venegas et al. 2014 |

| Perú | Loreto | N of Charupa | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pavayacu | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pongo Chinim | FMNH 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Ucayali | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Loreto | Yarina Cocha | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |