Speckled Forest-Pitviper |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrops taeniatus

English common names: Speckled Forest-Pitviper.

Spanish common names: Víbora moteada de árbol (Ecuador), estrellita (Colombia), jergón de árbol (Peru), mapanare liquenosa (Venezuela).

Recognition: ♂♂ 142.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 174.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. In its area of distribution, the Speckled Forest-Pitviper (Bothrops taeniatus) may be recognized by having the following combination of features: triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, prehensile1 (capable of grasping) tail, pattern of 22–48 blackish bands or blotches on a “lichenose” greenish to yellowish dorsum, low keels (longitudinal ridges) on the dorsal scales, and iris having bold black speckles.2–4 The tail-tip is usually reddish or pink in juveniles and dark green in adults. The most similar viper in Ecuador is B. pulcher, which has prominent keels on the dorsal scales and lacks bold black-speckles on the iris.

Picture: Adult female from Tiink, Morona Santiago, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Maycu Reserve, Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Uncommon. Bothrops taeniatus is an arboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen forests, palm-dominated swamps, forest borders, and plantations.2 Speckled Forest-Pitvipers are active at night especially after a warm day.5 They spend most of their time coiled, either on leaf-litter or on branches, shrubs, vines, and epiphytes 0.5–5 m above the ground.5 During the daytime, individuals usually remain perched on vegetation, but may occasionally be seen crawling at ground level or hidden under rotten logs.2,3

Speckled Forest-Pitvipers are ambush predators. Their diet includes rodents, opossums,3 lizards (such as Alopoglossus atriventris and Gonatodes), frogs, and centipedes.2,6,7 Juveniles attract prey by means of moving their brightly colored tails as a lure.3 Members of this species rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism,2 but may readily bite if attacked or harassed. In the wild, individuals of Bothrops taeniatus in some areas are heavily infested with parasitic roundworms.8

Bothrops taeniatus is a venomous snake (LD50 4.5 mg/kg) that is responsible for 0.2–5% of snakebites throughout its range.9,10 In humans, its venom causes intense pain, swelling, bruising, severe bleeding, blistering, fever, dizziness, decrease of muscle response, necrosis (death of tissues and cells), and presumably also death, although no fatalities have been reported.9–14 Fortunately, the antivenom available in Ecuador can, to a degree, neutralize the venom of B. taeniatus.10

What to do if you are bitten by a Speckled Forest-Pitviper?

|

Females of Bothrops taeniatus “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 7–17 young that are 24.4–40 cm in total length.2,8 In captivity, individuals can live up to 17 years,17 and probably much longer.

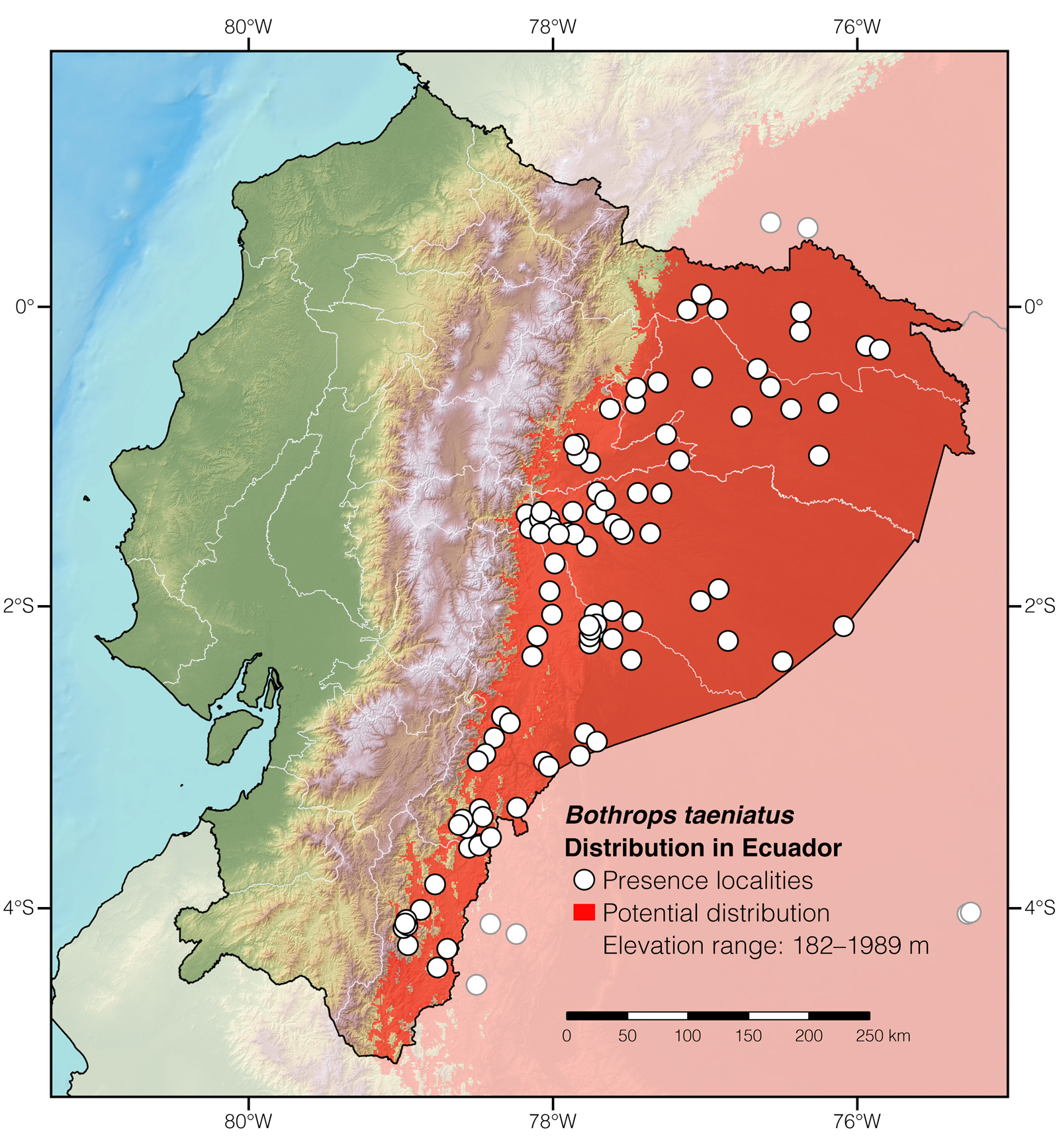

Conservation: Least Concern.18 Bothrops taeniatus is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed throughout the Amazon basin, a region that retains most of its original forest cover. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. We estimate that, in Ecuador, ~86.6% of the distribution range of B. taeniatus holds pristine forest.

Distribution: Bothrops taeniatus is native to an estimated 721,317 km2 area throughout the Amazon basin and adjacent foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.19

Etymology: The generic name Bothrops, which is derived from the Greek word bothros (meaning “pit”),20 refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils. The specific epithet taeniatus, which is derived from the Greek word taenia (meaning “ribbon”) and the Latin suffix -atus (meaning “provided with”), probably refers to the slender body of these vipers.3

See it in the wild: Speckled Forest-Pitvipers can be located with ~1–5% certainty in forested areas throughout the species' area of distribution in Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find Speckled Forest-Pitvipers are Río Zuñac Reserve, Podocarpus National Park, and Maycu Reserve. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

Special thanks to Alain Kormann for symbolically adopting the Speckled Forest-Pitviper and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Bothrops taeniatus. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Harvey MB, Aparicio J, Gonzales L (2009) Revision of the venomous snakes of Bolivia. II. The pitvipers (Serpentes: Viperidae). Annals of the Carnegie Museum 74: 1–37.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- Martins M, Marques OAV, Sazima I (2002) Ecological and phylogenetic correlates of feeding habits in Neotropical pitvipers of the genus Bothrops. In: Schuett GW, Höggren M, Douglas ME, Greene HW (Eds) Biology of the vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, 307–328.

- Roberts DT, Hammack SH (1995) Captive reproduction and husbandry of the speckled forest-pitviper Bothriopsis taeniata (Wagler) at the Dallas Zoo. Snake 27: 53–55.

- Warrell DA (2004) Snakebites in Central and South America: epidemiology, clinical features, and clinical management. In: Campbell JA, Lamar WW (Eds) The Venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 709–761.

- Smalligan R, Cole J, Brito N, Laing GD, Mertz BL, Manock S, Maudlin J, Quist B, Holland G, Nelson S, Lalloo DG, Rivadeneira G, Barragán ME, Dolley D, Eddleston M, Warrell DA, Theakston RDG (2004) Crotaline snake bite in the Ecuadorian Amazon: randomised double blind comparative trial of three South American polyspecific antivenoms. BMJ 329: 1129–1135.

- Silva Haad J (1982) Accidentes humanos por las serpintes de los géneros Bothrops y Lachesis. Memórias do Instituto Butantan 44: 403–423.

- Porto JM, Telli CA, Dutra TP, Alves LS, Bozza MT, Fin CA, Thiesen FV, Renner MF (2007) Biochemical and biological characterization of the venoms of Bothriopsis bilineata and Bothriopsis taeniata (Serpentes: Viperidae). Toxicon 50: 270–277.

- Torrez PQ, Duarte MR, Franca FO, Figueiredo L, Abati P, Campos LR, Pardal PP, Quiroga M, Mascheretti M, Boulos M (2009) First report of an accident with the speckled forest pit viper (Bothriopsis taeniata) in Brazil. Revista de la Sociedad Brasileña de Medicina Tropical 42: 342–344.

- Romero-Vargas FF, Rocha T, Cruz-Höfling AM, Rodrigues-Simioni L, Ponce-Soto LA, Marangoni S (2019) Biochemical characterization of a PLA2 Btae TX-I isolated from Bothriopsis taeniata snake venom: a pharmacological and morphological study. Journal of Clinical Toxicology 4: 1000197.

- Hardy DL (1994) Bothrops asper (Viperidae) snakebite and field researchers in Middle America. Biotropica 26: 198–207.

- Avau B, Borra V, Vandekerckhove P, De Buck E (2016) The treatment of snake bites in a first aid setting: a systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10: e0005079.

- Unpublished data by Ernesto Arbeláez.

- Hoogmoed MS, Nogueira C, Catenazzi A, Gonzales L (2019) Bothrops taeniatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.