Andean Forest-Pitviper |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrops pulcher

English common names: Andean Forest-Pitviper, Dusky Lancehead.

Spanish common names: Lorito machacui, loro mashaco, agua pitalala, yacu pitalala (Ecuador).

Recognition: ♂♂ 77.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 99.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. In its area of distribution, the Andean Forest-Pitviper (Bothrops pulcher) may be recognized by having the following combination of features: triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, prehensile (capable of grasping) tail, pattern of 29–37 pale-edged blackish bands or blotches on a greenish dorsum, prominent keels (enlarged longitudinal ridges) on the dorsal scales, and iris lacking bold black speckles. The tail-tip is usually cream or pink in juveniles and dark green in adults.1 The most similar viper is B. taeniatus, which has bold black-speckles on the iris and low keels on the dorsal scales.

Picture: Adult from Narupa Reserve, Napo, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Sumaco National Park, Napo, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female from Maycu Reserve, Zamora Chinchipe, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Sumaco National Park, Napo, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Rare to uncommon. Bothrops pulcher is an arboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen montane forests, forest borders, and plantations (of cassava and naranjilla).2,3 Andean Forest-Pitvipers are active at night especially after a warm day.4 They spend most of their time coiled on vegetation 0.6–6 m above the ground, but individuals also crawl at ground level during heavy rainfall.4 During the daytime, the vipers remain perched on vegetation.3 Andean Forest-Pitvipers are ambush predators. As juveniles, their diet includes invertebrates, which they attract by means of moving their brightly colored tails as a lure.2 Adults feed on frogs and rodents.2

Individuals of Bothrops pulcher rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism, but may readily bite if attacked or harassed.2,4 Bothrops pulcher is a venomous snake. In humans, its venom causes intense pain, bleeding, swelling, and presumably also death. Some bites entail no envenomation.2 Females of this species “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 13–14 young.5,6

What to do if you are bitten by an Andean Forest-Pitviper?

|

Conservation: Near Threatened.9 Bothrops pulcher is listed in this category because the species is distributed over an area which retains most of its forest cover, and therefore, is considered to be facing no major immediate threats of extinction. We estimate that, in Ecuador, ~79.5% of the habitat of B. pulcher holds pristine forest habitat. The most important threat to the long-term survival of the species is habitat destruction mostly due to mining and the expansion of the agricultural frontier.2

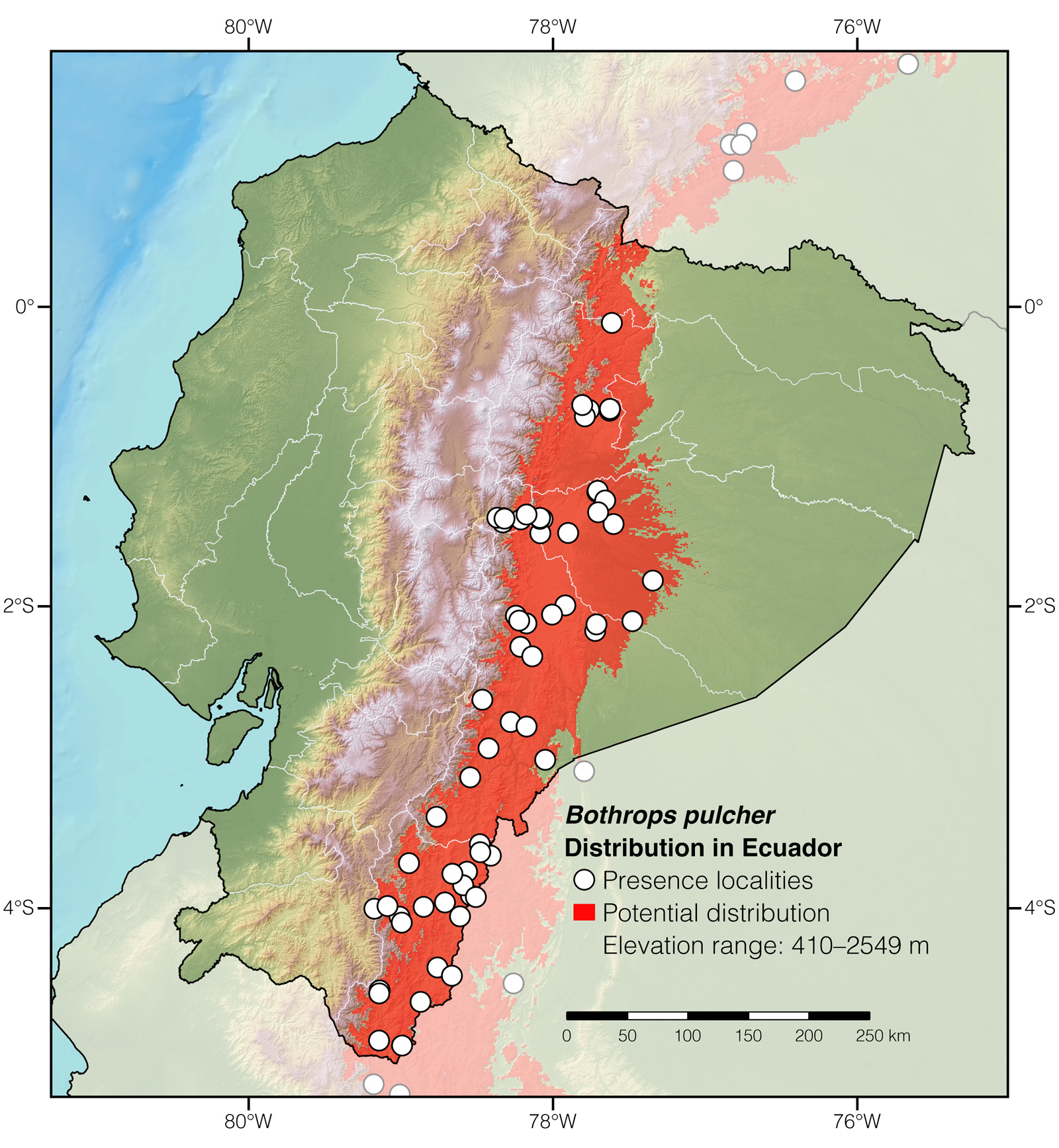

Distribution: Bothrops pulcher is native to the Amazonian foothills of the Andes in Colombia, Ecuador, and northeastern Peru. In Ecuador, the species occurs over an estimated 52,972 km2 area.

Etymology: The generic name Bothrops, which is derived from the Greek word bothros (meaning “pit”),10 refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils. The specific epithet pulcher, which is a Latin word meaning “beautiful,” refers to the attractive color pattern of this snake.1

See it in the wild: Andean Forest-Pitvipers can be located with ~1–5% certainty in forested areas throughout the species' area of distribution in Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find Andean Forest-Pitvipers are Narupa Reserve, Wildsumaco Wildlife Sanctuary, Río Zuñac Reserve, and San Francisco Biological Reserve. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

Special thanks to Thomas Kelafant, Michael Meyer, and Jennifer Roger for symbolically adopting the Andean Forest-Pitviper and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Bothrops pulcher. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Field notes of Jose Simbaña.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Field notes of Ernesto Arbeláez.

- Field notes of Darwin Núñez.

- Hardy DL (1994) Bothrops asper (Viperidae) snakebite and field researchers in Middle America. Biotropica 26: 198–207.

- Avau B, Borra V, Vandekerckhove P, De Buck E (2016) The treatment of snake bites in a first aid setting: a systematic review. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 10: e0005079.

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.