Published October 18, 2020. Updated November 30, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Orcés’ Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama orcesi)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Riama orcesi

English common names: Orcés’ Lightbulb-Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija minadora de Orcés.

Recognition: ♂♂ 15.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.9 cm. ♀♀ 13.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.9 cm..1,2 Lightbulb-lizards are easily distinguishable from other lizards by their fossorial habits and extremities so short that the front and hind limbs cannot reach each other.1,2 Riama orcesi is one of three species of its genus known to occur in Napo province. Riama orcesi differs from the other two species (R. anatoloros and R. raneyi) by having light orangish dorsolateral stripes on the anterior portion of the tail (Fig. 1). Individuals of R. orcesi further differ from those of R. raneyi by being smaller, more colorful, and having a complete series of superciliary scales.2 Adult males differ from females by having broader heads, darker colored venters,3 and, usually, a bright reddish tail.

Figure 1: Individuals of Riama orcesi from Napo province, Ecuador: Río Quijos (); Virgen de Guacamayos ().

Natural history: Riama orcesi is a rarely seen fossorial lizard that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed cloud forests and high evergreen montane forests. It also occurs in areas containing a mixture of pastures, crops, rural houses, and remnants of native vegetation.4 Lizards of this species spend most of their lives in tunnels they excavate in areas of soft soil or under rocks, logs, and debris.4 Females lay clutches of two eggs under rocks.3 When dug up or otherwise exposed, these shy reptiles will quickly flee underground. If captured, they may bite or readily shed the tail. Orcés’ Lightbulb-Lizards are susceptible to high temperatures, dying if exposed to the sun or even if handled for longer than just a few seconds. An antpitta was seen preying upon an individual of R. orcesi.5 Riama orcesi can be found living alongside R. raneyi in the valley of the Papallacta river.2 Differences like larger body size, but comparatively shorter limbs in R. raneyi could be allowing the coexistence between the two species by influencing the use of different microhabitats.2

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Riama orcesi is listed in this category, instead of Vulnerable,6,7 because the species occurs in four major protected areas (Antisana Ecological Reserve, Cayambe Coca National Park, Colonso Chalupas Biological Reserve, and Sumaco National Park) and is distributed over an area that retains the majority (~93.4%) of its original forest cover.8 Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

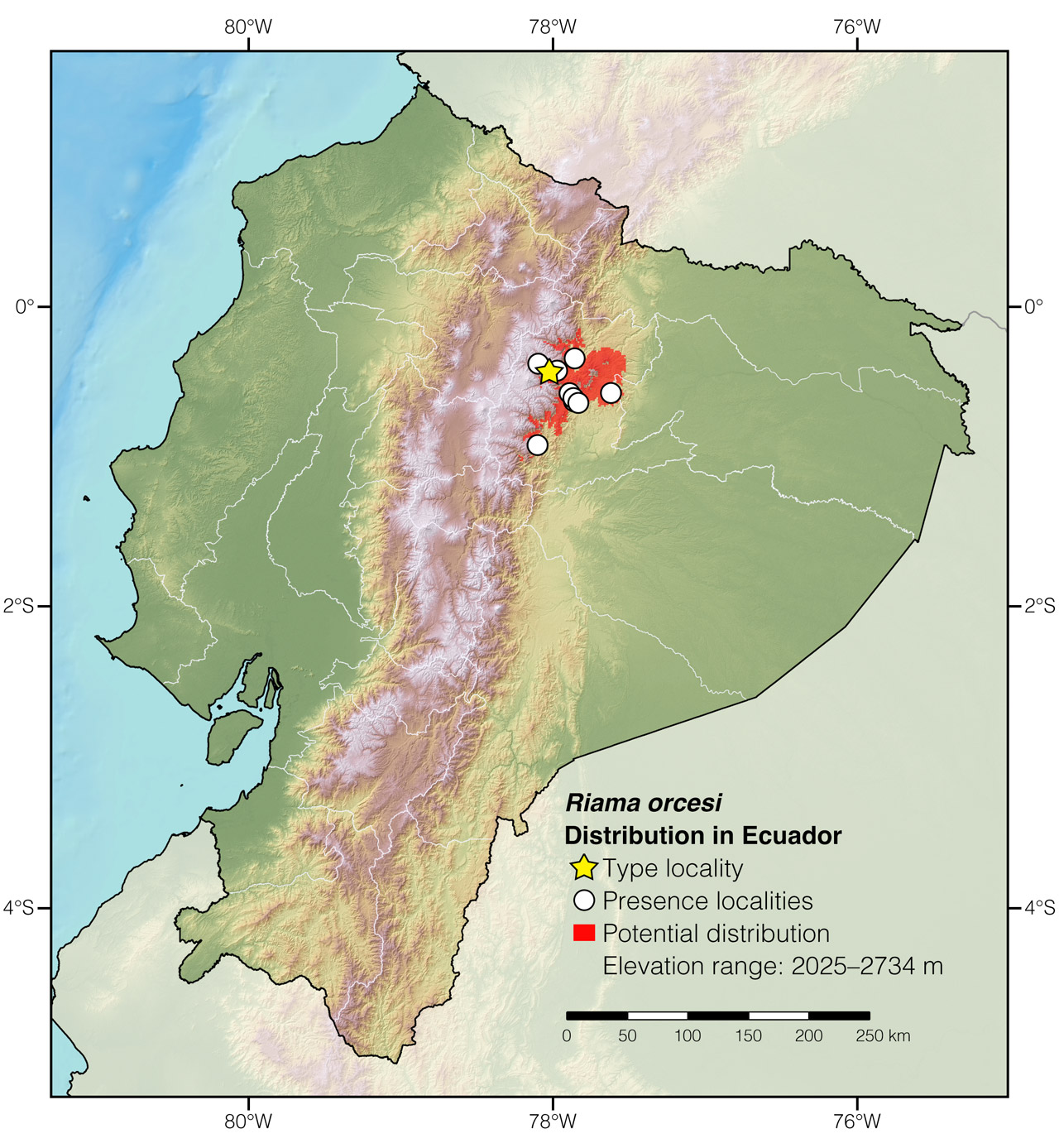

Distribution: Riama orcesi is endemic to an area of approximately 2,497 km2 in the Amazonian slopes of the Andes of northern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Riama orcesi in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Cuyuja, 3.3 km ESE of*, Napo province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Riama does not appear to be a reference to any feature of this group of lizards, but a matter of personal taste. John Edward Gray usually selected girls’ names to use on reptiles.9–12 The specific epithet orcesi honors Dr. Gustavo Orcés (1903–1999), in recognition of his many contributions to the herpetology of Ecuador.3

See it in the wild: Orcés’ Lightbulb-Lizards are recorded rarely unless they are actively searched for by digging in areas of soft soil or by turning over rocks and logs in suitable habitats. Around the town Cuyuja, a targeted search of least four hours usually result in 3–7 individuals.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Amanda Quezada, Harry Turner, and Jorge Castillo for their help and companionship during the search of specimens of Riama orcesi in the field. Thanks to Frank Pichardo for providing natural history data of R. orcesi. Thanks to Amanda Quezada for the post-processing of images.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Miguel Ángel Méndez-GaleanobAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Sistemática Molecular, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CampercAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Méndez-Galeano MA (2023) Orcés’ Lightbulb-Lizard (Riama orcesi). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/MNSV6360

Literature cited:

- Pazmiño-Otamendi G (2022) Riama orcesi. In: Torres-Carvajal O, Pazmiño-Otamendi G, Ayala-Varela F, Salazar-Valenzuela D (Eds) Reptiles del Ecuador. Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Available from: https://bioweb.bio

- Kizirian DA (1996) A review of Ecuadorian Proctoporus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) with descriptions of nine new species. Herpetological Monographs 10: 85–155. DOI: 10.2307/1466981

- Kizirian DA (1995) A new species of Proctoporus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) from the Andean Cordillera Oriental of northeastern Ecuador. Journal of Herpetology 29: 66–72. DOI: 10.2307/1565087

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photographic record by Frank Pichardo.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Valencia J, Brito J, Almendáriz A, Muñoz G (2019) Riama orcesi. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T50950530A50950537.en

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) Description of a new genus of ophisaurean animal, discovered by the late James Hunter in New Holland. Treuttel, Würtz & Co., London, 40 pp.

- Gray JE (1831) A synopsis of the species of the class Reptilia. In: Griffith E, Pidgeon E (Eds) The animal kingdom arranged in conformity with its organization. Whittaker, Treacher, & Co., London, 1–110.

- Gray JE (1838) Catalogue of the slender-tongued saurians, with descriptions of many new genera and species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 1: 274–283.

- Gray JE (1845) Catalogue of the specimens of lizards in the collection of the British Museum. Trustees of the British Museum, London, 289 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Riama orcesi in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Napo | Above El Chaco | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Between Papallacta and Baeza | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Colonso Chalupas | Elicio Tapia, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cosanga, 1 km N of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cuyuja | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cuyuja, 3.3 km ESE of* | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cuyuja, 7 km E of | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cuyuja, 9 km E of | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Estación repetidora | Jose Simbaña, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guango Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sendero Guacamayos | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sumaco camp 2 | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena–Quito 1 | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena–Quito 2 | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Vertiente E Volcán Sumaco | Pazmiño-Otamendi 2020 |