Published October 10, 2019. Updated May 28, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed.

Western Galápagos Racer (Pseudalsophis occidentalis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Pseudalsophis occidentalis

English common names: Western Galápagos Racer, Fernandina Racer.

Spanish common name: Culebra occidental de Galápagos.

Recognition: ♂♂ 128.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 123.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=96.8 cm..1,2 Pseudalsophis occidentalis is one of two snake species known to occur on Fernandina Island, Isabela Island, and two of their surrounding islets.1,2 It is characterized by having a pale grayish brown dorsum with a series of dark dorsolateral spots or a complete blackish mid-dorsal stripe accompanied by pale dorsolateral stripes (Fig. 1).1–4 There is usually a pair of contrasting light cream nuchal blotches on the nape.4 This pattern differentiates it from the black-banded P. darwini, a smaller co-occurring snake that lacks light spots on the nape.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Pseudalsophis occidentalis from Galápagos, Ecuador: Punta Espinoza, Fernandina Island (); Tagus Cove, Isabela Island (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Pseudalsophis occidentalis is a diurnal snake that can occur in extremely high densities in coastal volcanic rock areas,2–5 occurring also in shrublands, agricultural fields, and peri-urban areas.6 Western Galápagos Racers are typically seen swiftly moving on bare soil, on sand, or on lava blocks.2 Their activity occurs throughout the day, but usually not during hot midday hours.2 Snakes of this species are mildly venomous, which means their bite is dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.1 They are foraging predators and their diet consists of lizards (Microlophus albemarlensis and Phyllodactylus simpsoni), juveniles of both the marine (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) and the land (Conolophus subcristatus) iguana, birds and their eggs, rodents, fish, and insects.5 Cannibalism and scavenging behavior have also been recorded in this species.2,5 Although generally solitary, these racers congregate in groups of dozens of individuals during the hatching season of Marine Iguanas from May to June in some coastal localities of Fernandina Island.2 There are recorded instances of predation on members of this species by hawks.2

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..7 Pseudalsophis occidentalis is listed in this category because the species has high population densities and, presumably, is not undergoing population declines or facing major immediate threats of extinction.7 Fernandina is one of the most pristine islands in Galápagos and is currently free of introduced animals that may prey upon snakes. The threats that this racer snake faces in Fernandina are volcanic eruptions and the potential introduction of aggressive exotic predators, mainly rats and cats. In Isabela, conservation challenges are more complex since the island has several introduced species, including humans, that may impact the snake’s population.2

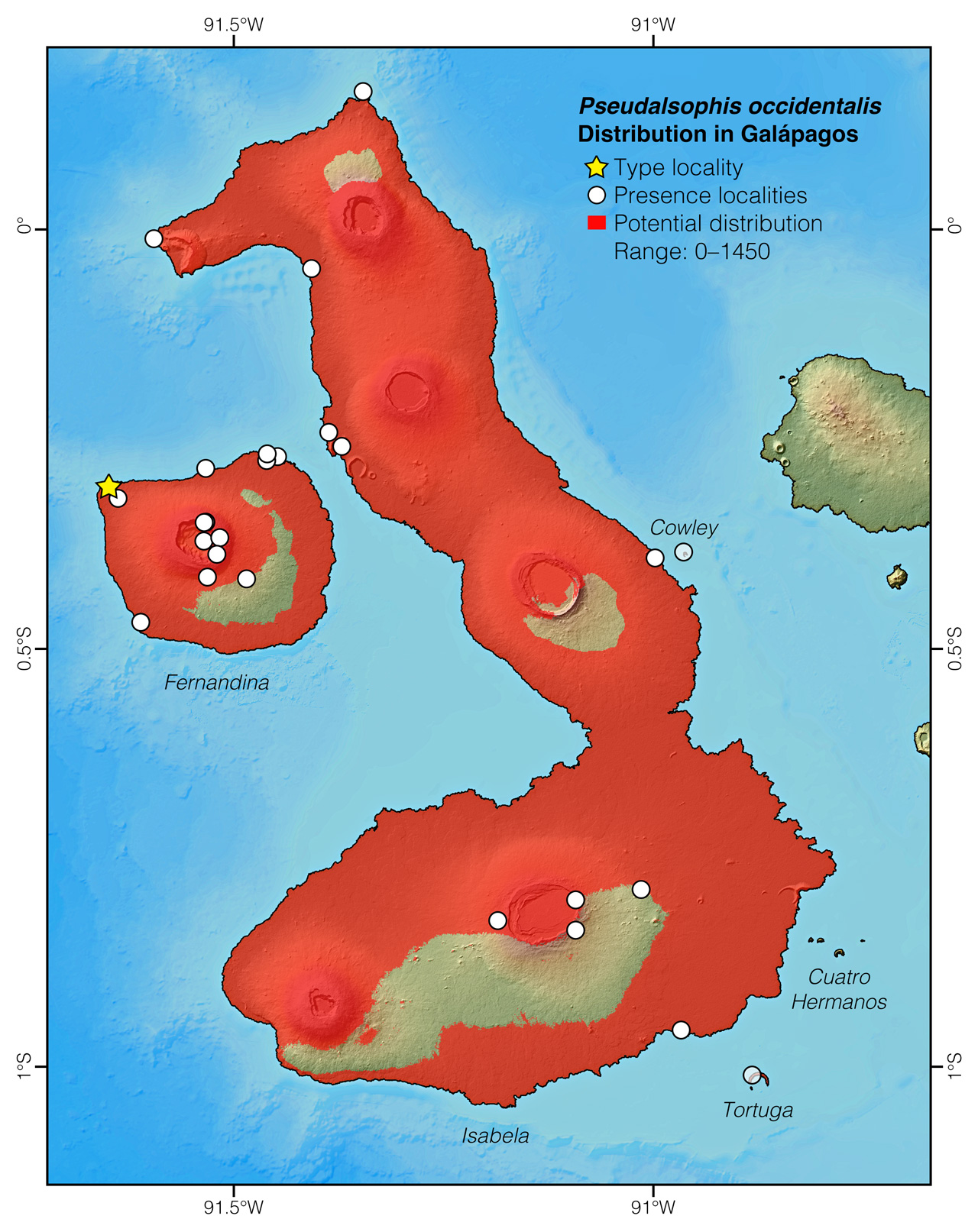

Distribution: Pseudalsophis occidentalis is endemic to Fernandina and Isabela islands, as well as two of their surrounding islets (Cowley and Tortuga) in Galápagos, which collectively account for an area of 5,313 km2 (Fig. 2). However, this species probably occurs throughout a much smaller area. Galápa- gos, Ecuador.

Figure 2: Distribution of Pseudalsophis occidentalis in Galápagos. The star corresponds to the type locality: Cabo Douglas, Fernandina Island. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pseudalsophis comes from the Greek words pseudo (=false) and Alsophis (a genus of Caribbean snakes), referring to the similarity between snakes of the two genera.1 The specific epithet occidentalis is a Latin word meaning “of the west.”8 It refers to the species’ distribution on the western islands of Galápagos.4

See it in the wild: Western Galápagos Racers can be seen with almost complete certainty at Punta Espinoza, Fernandina Island, especially during the hatching season of the Marine Iguanas (from May to June).

Special thanks to Michael Lavery for symbolically adopting the Western Galápagos Racer and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Robert A ThomascAffiliation: Loyola University, New Orleans, United States. and Luis Ortiz-CatedraldAffiliation: Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand.

Photographer: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Western Galápagos Racer (Pseudalsophis occidentalis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/MHGU8840

Literature cited:

- Zaher H, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Rodrigues MT, Graboski R, Machado FA, Altamirano-Benavides M, Bonatto SL, Grazziotin FG (2018) Origin and hidden diversity within the poorly known Galápagos snake radiation (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Systematics and Biodiversity 16: 614–642. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2018.1478910

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Thomas RA (1997) Galápagos terrestrial snakes: biogeography and systematics. Herpetological Natural History 5: 19–40.

- Van Denburgh J (1912) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. IV. The snakes of the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 323–374.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Reyes-Puig C (2023) Natural history and conservation of the Galápagos snake radiation. In: Lillywhite HB, Martins M (Eds) Islands and snakes. Oxford University Press, 158–182. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197641521.003.0009

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Márquez C, Yánez-Muñoz M (2022) Pseudalsophis occidentalis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T190540A217764795.en

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pseudalsophis occidentalis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cabo Douglas, 1.6 km SE of | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cabo Douglas* | Van Denburgh 1912 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cabo Hammond | Merlen & Thomas 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cape Berkeley | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Santuario, 5 km NE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Estación El Cura | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Fernandina, north coast | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | In front of Cowley Islet | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Islote Cowley | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | La Cumbre volcano | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Bravo | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Villamil | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Albemarle | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Espinoza | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Espinoza, 1 km SE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Espinoza, 1.6 km S of | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Rim of Sierra Negra crater | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Sendero Sierra Negra | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Shoreline of crater | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Sierra Negra, western rim | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Tagus Cove | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Tagus Cove, 3 km NW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Tortuga Islet (Brattle) | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Volcán La Cumbre, northeastern rim | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Volcán La Cumbre, northern rim | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Volcán La Cumbre, southeastern rim | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Volcán La Cumbre, southeastern slope | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Volcán La Cumbre, southern slope | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |