Published October 10, 2019. Updated May 26, 2024. Open access.

Central Galápagos Racer (Pseudalsophis dorsalis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Pseudalsophis dorsalis

English common name: Central Galápagos Racer.

Spanish common name: Culebra central de Galápagos.

Recognition: ♂♂ 110.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=83.0 cm. ♀♀ 95 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1,2 Pseudalsophis dorsalis is the only snake known to occur on Santa Fe Island, Edén Islet, and Venecia Islet, and one of two species occurring on Santa Cruz, Baltra, and Seymour Norte islands.2,3 It is characterized by a pale grayish-brown dorsum with a series of irregular dark spots or dark longitudinal stripes (Fig. 1). The other co-occurring snake species is P. steindachneri, from which it differs by being larger and lacking golden speckled lateral black bands.2

Figure 1: Individuals of Pseudalsophis dorsalis from El Miedo, Santa Fe Island, Galápagos, Ecuador.

Natural history: Pseudalsophis dorsalis is a diurnal snake that occurs naturally in coastal volcanic rock areas, dry shrublands, dry grasslands, and seasonally dry forests, with individuals occasionally venturing into rural gardens and agricultural fields.2–5 These snakes are typically seen swiftly moving on soil, lava blacks, or along dry stream beds during daytime and sometimes at night, but usually not during hot midday hours.2–5 When not active, they remain hidden under loose tree bark, under lava blocks, or in abandoned iguana burrows.5 Galápagos racer snakes in general are mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.2 They are active foragers and their diet includes geckos (Phyllodactylus barringtonensis and P. galapagensis), lava lizards (Microlophus barringtonensis and Microlophus indefatigabilis), juveniles of both the marine (Amblyrhynchus cristatus) and the land (Conolophus pallidus and C. subcristatus) iguanas, rodents, sea birds, eggs of Galápagos doves, and insects.2,3,6 There is also a record of cannibalism in this species.7 Owls and mockingbirds have been recorded preying upon or attacking, respectively, individuals of this species.8,9

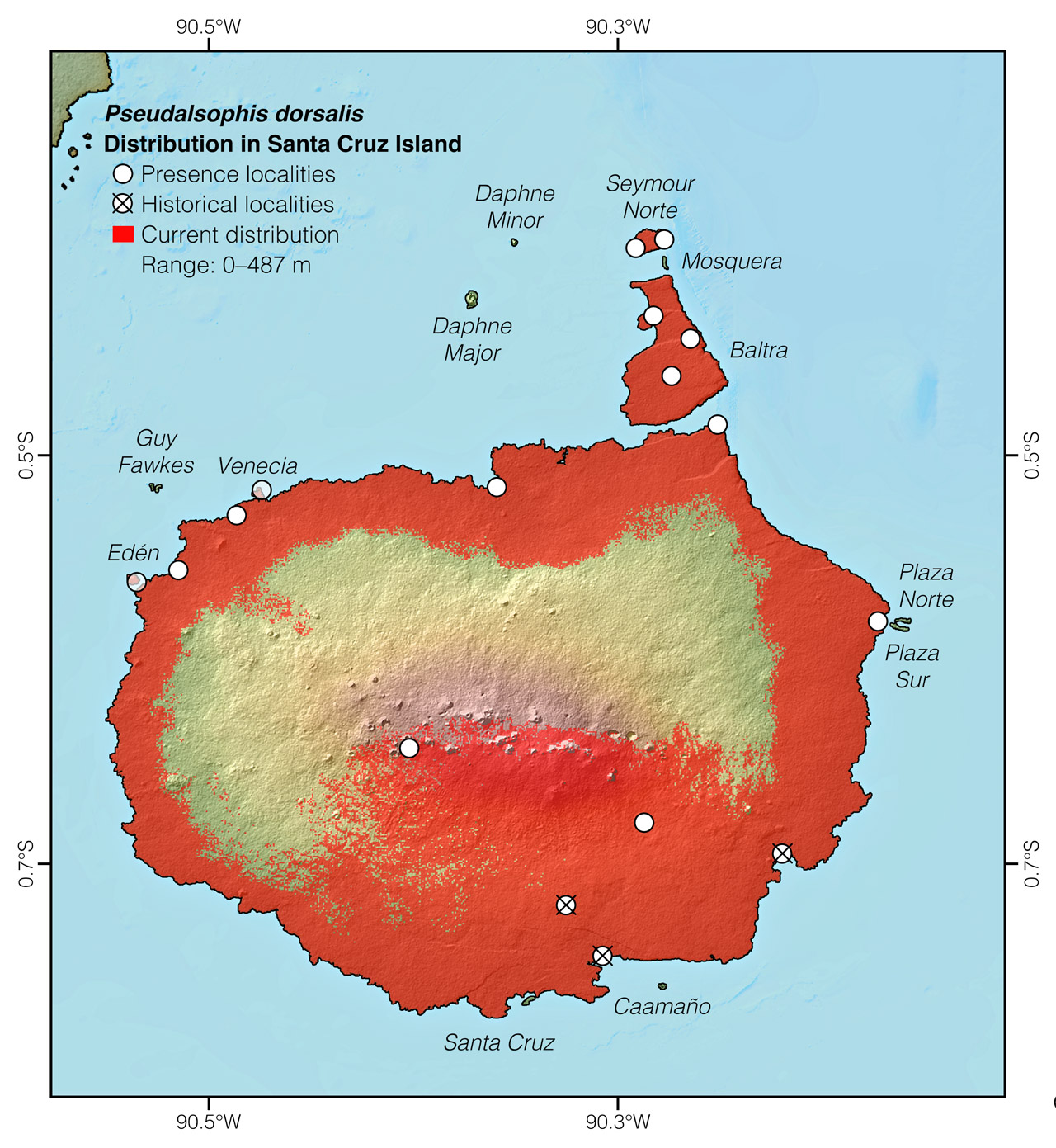

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..4 Pseudalsophis dorsalis is included in this category because the species is found on several uninhabited islands and one inhabited island in the Galápagos archipelago, with available evidence suggesting high population densities in some of them. Although the species is currently not considered to be at risk of extinction, its population status on Santa Cruz is uncertain and probably severely depleted as a result of the introduction of cats and rats.3,4 However, unlike previously reported,2 P. dorsalis has not been entirely extirpated from Santa Cruz. Some isolated reports3,5,7 suggest that the species occurs in low densities in some parts of the island.

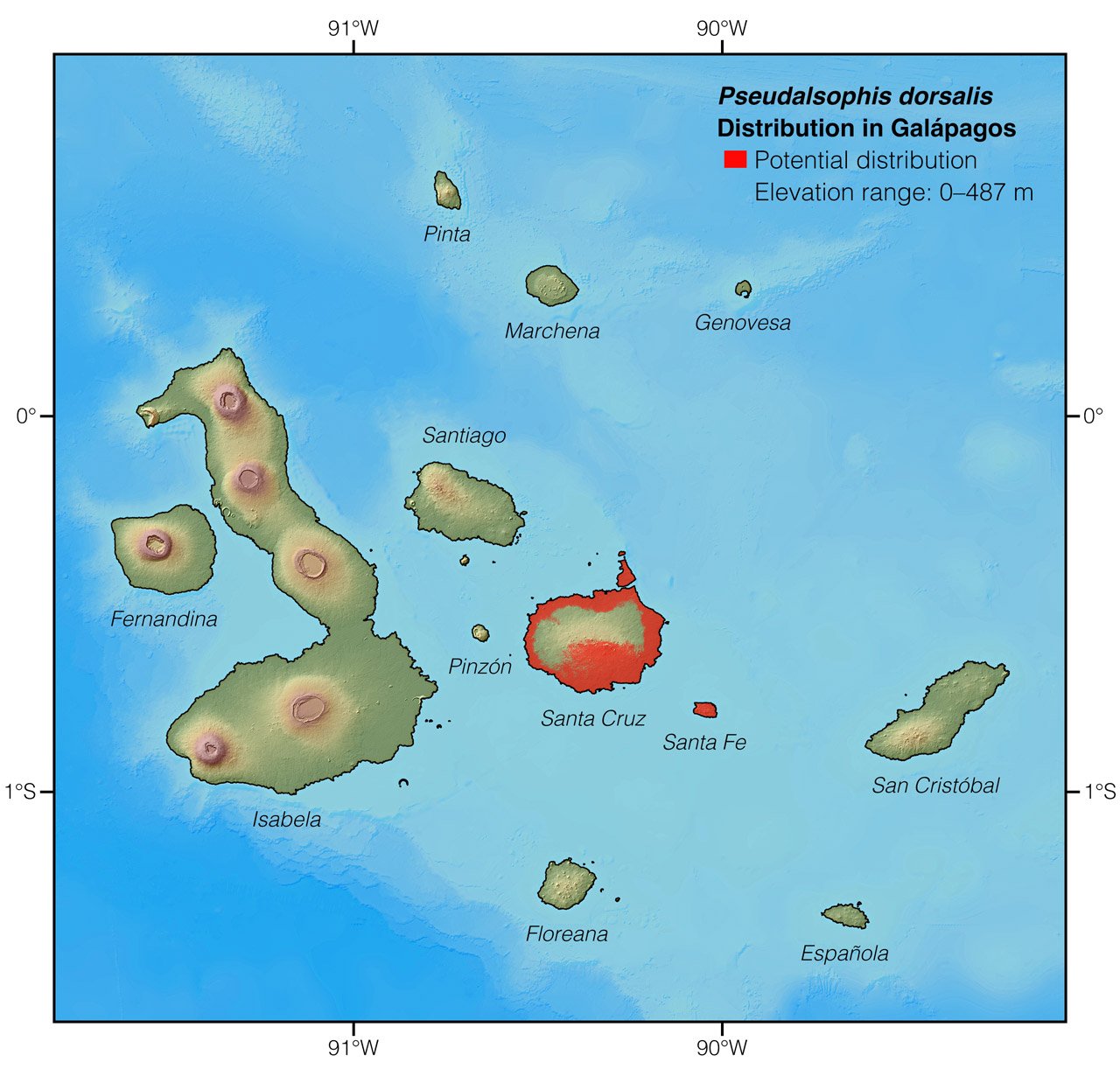

Distribution: Pseudalsophis dorsalis is endemic to an area of approximately 637 km2 area in four islands (Baltra, Seymour Norte, Santa Cruz, and Santa Fe) and two islets (Edén and Venecia) in central Galápagos, Ecuador (Figs 2, 3). The species is believed to have been extirpated from southern Santa Cruz Island.

Figure 2: Distribution of Pseudalsophis dorsalis in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Pseudalsophis dorsalis in Santa Cruz Island. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pseudalsophis comes from the Greek words pseudo (=false) and Alsophis (a genus of Caribbean snakes), referring to the similarity between snakes of the two genera.1 The specific epithet dorsalis comes from the Latin words dorsum (=back) and the suffix -alis (=pertaining to).10 It probably refers to the bold dorsal stripe present in some individuals.2

See it in the wild: Like most snakes in Galápagos, Central Galápagos Racers are secretive animals, but, with some luck, they can be seen during tourism day trips to Santa Fe and Seymour Norte islands. In Seymour Norte, snakes of this species are more frequently observed in sea bird nesting areas during the first hours after sunrise or right before sunset.

Author and photographer: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Central Galápagos Racer (Pseudalsophis dorsalis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ERII2322

Literature cited:

- Zaher H, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Rodrigues MT, Graboski R, Machado FA, Altamirano-Benavides M, Bonatto SL, Grazziotin FG (2018) Origin and hidden diversity within the poorly known Galápagos snake radiation (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Systematics and Biodiversity 16: 614–642. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2018.1478910

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Reyes-Puig C (2023) Natural history and conservation of the Galápagos snake radiation. In: Lillywhite HB, Martins M (Eds) Islands and snakes. Oxford University Press, 158–182. DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197641521.003.0009

- Márquez C, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz M (2022) Pseudalsophis dorsalis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T190538A217764645.en

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Ortiz-Catedral L, Christian E, Skirrow MJA, Rueda D, Sevilla C, Kumar K, Reyes EMR, Daltry JC (2019) Diet of six species of Galapagos terrestrial snakes (Pseudalsophis spp.) inferred from faecal samples. Herpetology Notes 12: 701–704.

- Sollis HE (2020) Conservation of the Central Galapagos Racer (Pseudalsophis dorsalis) in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. MSc thesis, Massey University, 257 pp.

- Steadman DW (1982) Fossil birds, reptiles, and mammals from isla Floreana, Galápagos Archipelago. PhD Thesis, Tucson, United States, The University of Arizona.

- Van Denburgh J (1912) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. IV. The snakes of the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 323–374.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pseudalsophis dorsalis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Academy Bay | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Baltra, FAE1 | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Baltra, Parque Eólico | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Baltra, road to airport | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Barrington Bay | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Barrington Bay, 2.5 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cerro Dragón | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Conway Bay | Thomas 1997 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Edén islet | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Miedo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Miedo, 200 m SW of | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Trapiche | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Encañada | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Halfway along Encañada | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Iguana colony | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Las Bachas, 3 km SW of | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Gemelos, 3 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerta de la Aguada | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Ayora, 3 km NW of | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Carrión | Cisneros-Heredia & Reyes-Puig 2023 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Santa Cruz, near Plazas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Santa Fe, centro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Santa Fe, meseta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Santa Fe, NE end | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Seymour Norte | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Seymour Norte, east of island | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Venecia Islet | Arteaga et al. 2013 |