Manabí Hognosed-Pitviper |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Porthidium arcosae

English common names: Manabí Hognosed-Pitviper.

Spanish common names: Sabanera, morera, imperiosa.

Recognition: ♂♂ 77.2 cm ♀♀ 63.3 cm. In its area of distribution, The Manabí Hognosed-Pitviper (Porthidium arcosae) is the only snake having a triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits in the loreal region, an upturned snout, and a pattern of alternating cream and dark brown rectangular marks on the dorsum.

Picture: Adult from Parque Nacional Machalilla, Manabí, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Locally frequent, especially during April and May, at the end of the rainy season.1 Porthidium arcosae is a primarily nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed dry to semideciduous forests, dry shrublands, savannas, plantations, rural gardens, and human settlements.2,3 Manabí Hognosed-Pitvipers are mostly active at night (17:20–21:48), but may also occasionally be seen moving during the daytime (8:00–13:30), especially after short periods of heavy precipitation.1 Usually, they hide during the day, sleeping coiled under ground debris and trunks.2 Snakes of this species are terrestrial ambush predators.3 Juveniles feed mostly on lizards (Holcosus septemlineatus, Microlophus occipitalis, and Dicrodon guttulatum), whereas adults feed mostly on rodents, but may occasionally consume members of their own species.1,4 Porthidium arcosae is venomous (LD50 3.5 mg/kg).5 Its venom is hemotoxic and, in humans, causes intense pain, inflammation, and hematomas.1 However, human fatalities have not been reported, and patients may recover without the use of antivenom.1 Manabí Hognosed-Pitvipers rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism, but may readily bite if attacked or harassed.3 Males of P. arcosae fight with each other over access to females.2 Copulation lasts up to 24 minutes, and females may “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) up to 11 young.2 In captivity, individuals can live up to 14 years.2

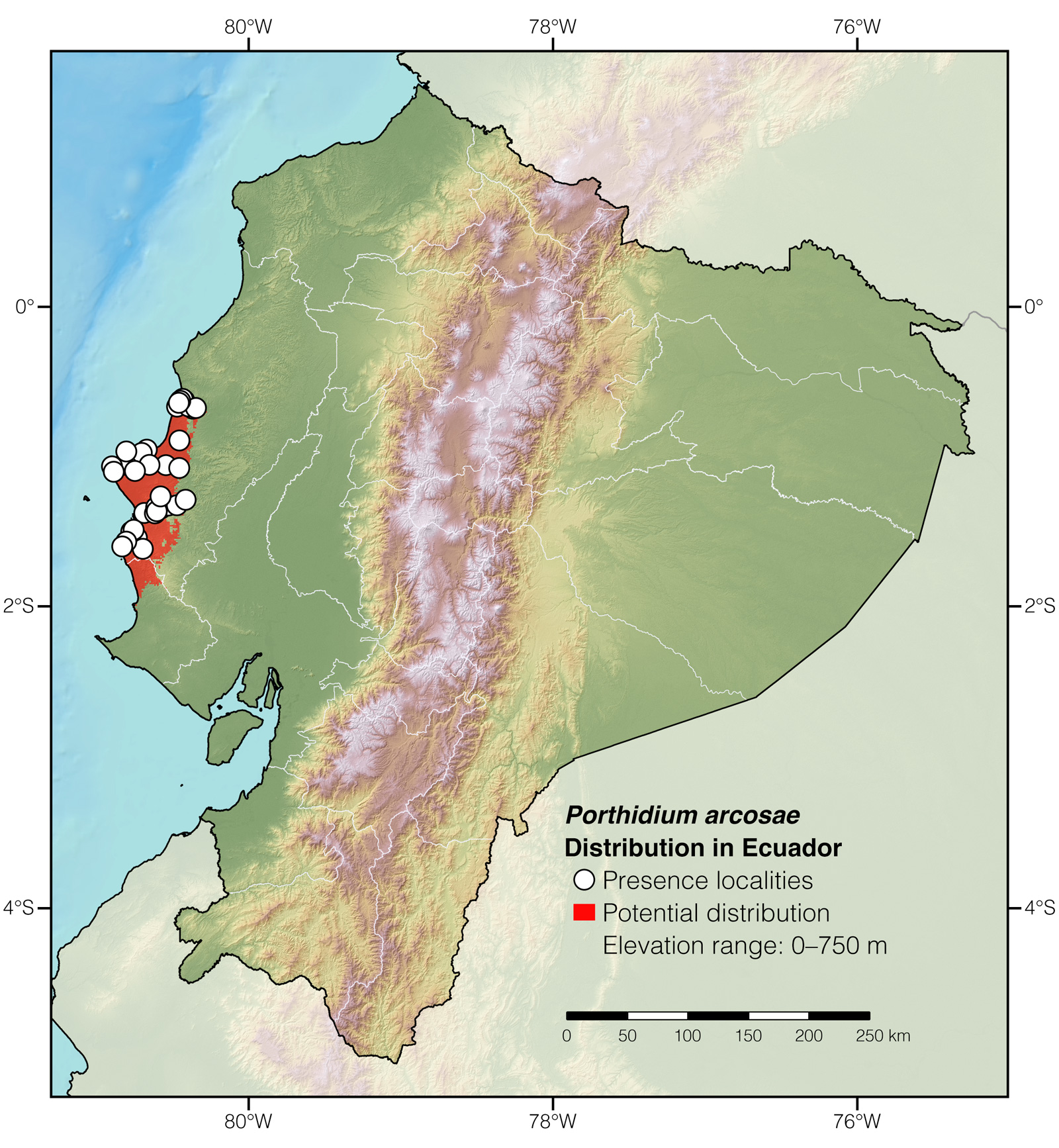

Conservation: Endangered.6 Porthidium arcosae is listed in this category because the species has a limited geographic distribution (~5,206 km2) and its habitat is rapidly declining in extent and quality.1 We estimate that ~36% of the habitat of P. arcosae has already been destroyed. In addition to habitat loss, the species faces the threat of direct killing.3

Distribution: Porthidium arcosae is endemic to an estimated 5,206 km2 area in the Tumbesian lowlands of the central Pacific coast of Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Porthidium, which is derived from the Greek word portheo (meaning “destroy”) and the Latin suffix -idus (meaning “having the nature of”), apparently refers to the characteristics of the venom.7 The specific epithet arcosae honors Laura Arcos of the Biology Department of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador.7

See it in the wild: Manabí Hognosed-Pitvipers can be located with ~2–20% certainty, especially between January and May in forested areas throughout the species' area of distribution. Some of the best localities to find Manabí Hognosed-Pitvipers are Parque Nacional Machalilla and Reserva Natural Punta Gorda. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

Special thanks to Grégoire Meier for symbolically adopting the Manabí Hognosed-Pitviper and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Porthidium arcosae. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Vaca-Guerrero GV, Garzón K (2011) Natural history, potential distribution and conservation status of the Manabi Hognose Pitviper Porthidium arcosae (Schätti & Kramer, 1993), in Ecuador. Herpetozoa 23: 31–43.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Acosta-Vásconez N, Carrera M, Peñaherrera E, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2018) Predation on the teiid lizard Dicrodon guttulatum Duméril and Bibron, 1839 by the pitviper Porthidium arcosae Schätti and Kramer, 1993. Herpetology Notes 11: 391–393.

- Terán MC, Lomonte B (2016) Actividad letal de seis venenos de serpientes de importancia médica en el Ecuador. Revista Ecuatoriana de Medicina y Ciencias Biológicas 37: 25–30.

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.