Published October 10, 2019. Updated January 21, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

San Cristóbal Lava-Lizard (Microlophus bivittatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Tropiduridae | Microlophus bivittatus

English common name: San Cristóbal Lava-Lizard.

Spanish common name: Lagartija de lava de San Cristóbal.

Recognition: ♂♂ 26.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=9.2 cm. ♀♀ 23.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.9 cm..1,2 Microlophus bivittatus is easily distinguishable from other co-occurring lizards by having keeled scales on the tail, a skin fold above the shoulder, a raised mid-dorsal crest, and a conspicuously enlarged interparietal scale. Microlophus bivittatus is the only lava lizard occurring on San Cristóbal Island and Lobos Islet. Males and females of this species differ from each other in size, shape, and coloration. Adult males are larger and easily recognized by their raised middorsal crest (Fig. 1). They also have a black mark just above the shoulder. Adult females may be recognized by their bright orange coloration on the throat and lower flanks of the body.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Microlophus bivittatus from Galápagos, Ecuador: Puerto Chino, San Cristóbal Island (); Islote Lobos (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Microlophus bivittatus is a diurnal lizard that inhabits volcanic rock areas, dry shrublands, dry grasslands, deciduous forests, and urban areas.1 San Cristóbal Lava-Lizards occupy 85–813 m2 territories, spending up to ~95% of the time on rocks, but also on soil, leaf-litter, grass, shrubs, cacti, and trees within 4.1 m from the ground.1,3 During the hottest hours of the day, they may remain active under the shade, moving among rock crevices and within vegetation.3,4 At night, they sleep in rock crevices, under leaf-litter, among shrubs, in grass clumps, or on tree branches.3 San Cristóbal Lava-Lizards are generalist foragers that feed mostly on ants, but also on moths, crickets, roaches, dragonflies, crabs, centipedes, spiders, worms, and plant material such as fruits and seeds.5–7 There are recorded instances of predation on lizards of this species, including by egrets,8 cats,9 and snakes (Pseudalsophis eibli).1 The breeding season takes place between February and March.3 Males routinely perform pushup displays and fight with one another, but are generally unable to keep their territories free from other males.3 Females lay 1–4 eggs per clutch.4

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..10 Microlophus bivittatus is listed in this category because the species is facing predation by housecats,9 although it has not been conclusively shown to have undergone population declines due to this threat. It is clear, however, that cats represent a major conservation problem for native animals in San Cristóbal.9,11 A major eradication program should be put in place for feral cats, combined with much stronger control and mandatory sterilization of domestic cats.

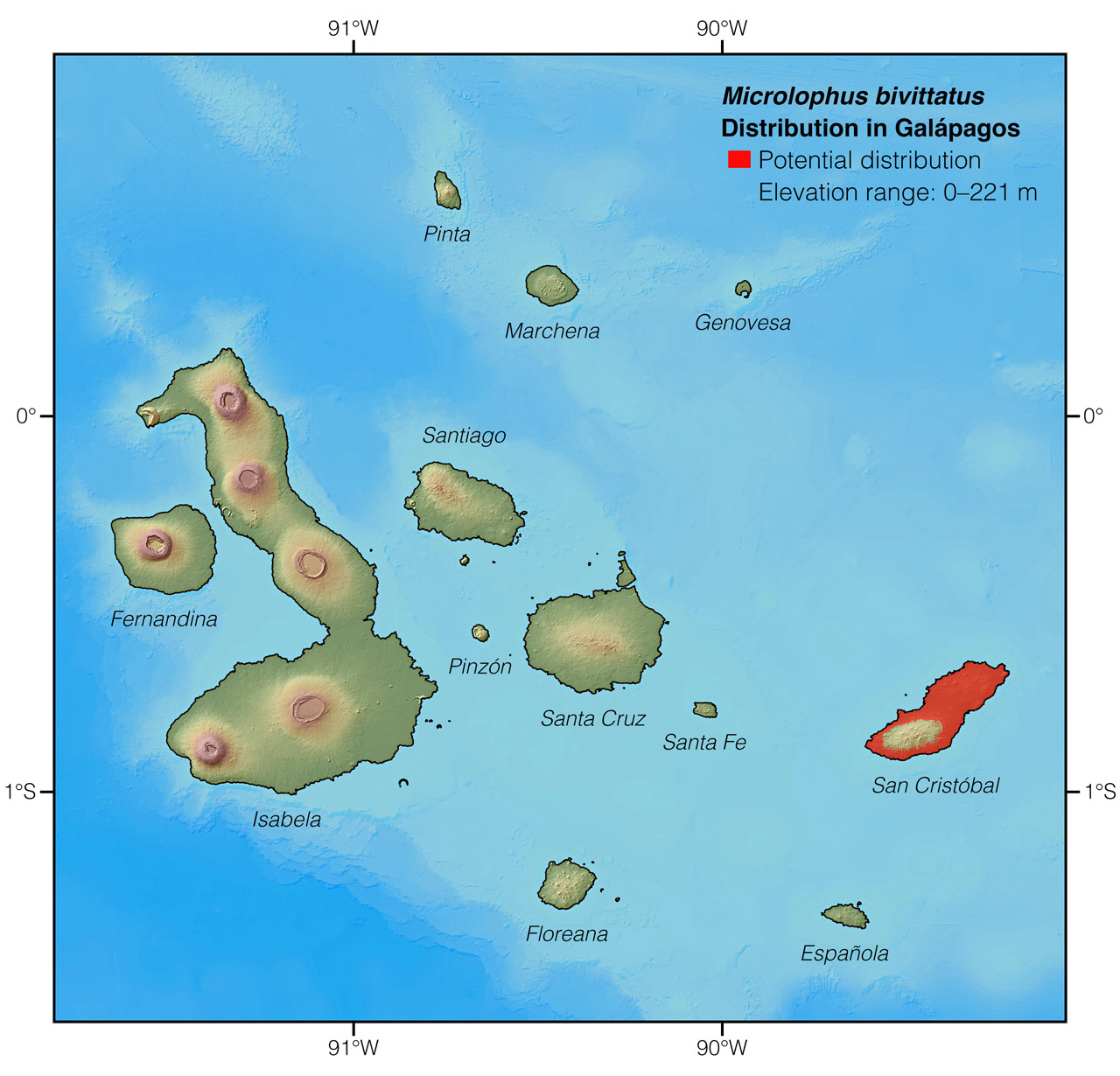

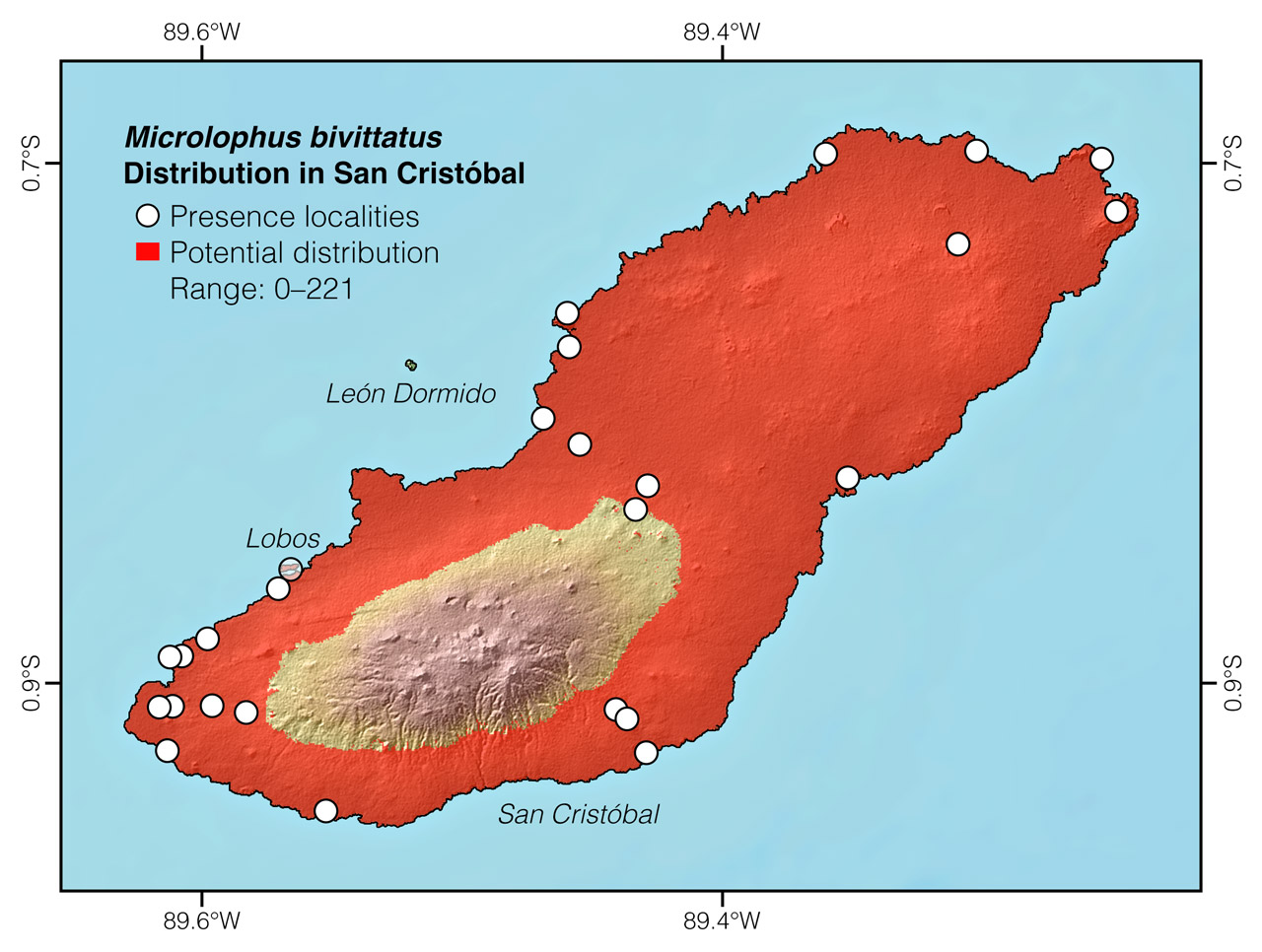

Distribution: Microlophus bivittatus is endemic to an area of approximately 447 km2 in San Cristóbal Island and Lobos Islet, Galápagos, Ecuador (Figs 2, 3).

Figure 2: Distribution of Microlophus bivittatus in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Microlophus bivittatus in San Cristóbal Island. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Microlophus comes from the Greek words mikros (=small) and lophos (=crest).1 The specific epithet bivittatus comes from the Latin words bi (=two) and vitta (=band),12 and refers to the dorsal longitudinal bands.1

See it in the wild: San Cristóbal Lava-Lizards can be seen year-round with almost complete certainty on the outskirts of Puerto Baquerizo, especially along the trail leading from the town to Punta Carola.

Authors: Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. Gabriela Aguiar,bIndependent researcher, Quito, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasamincAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Edgar Benavides,dAffiliation: Yale University, New Have, USA. John Rowe,eAffiliation: Alma College, Alma, USA. and Cruz MárquezfAffiliation: University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Photographers: Jose VieiragAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,hAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Aguiar G, Guayasamin JM (2024) San Cristóbal Lava-Lizard (Microlophus bivittatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/FRUZ9006

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Vintimilla Palacios CP (2013) Perfil de comportamiento y territorialismo de la lagartija de lava de San Cristóbal (Microlophus bivittatus) durante la época no reproductiva. MSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 61 pp.

- Rowe JW, Martin CE, Clarck DL (2019) Habitat use and spatial ecology of three Microlophus lizard species from Santa Cruz and San Cristóbal islands, Galápagos, and the coastal dry forest of Machalilla, Ecuador. Herpetological Review 50: 43–51.

- Koenig MN (2017) The relationship between sex and territorial behavior in the San Cristóbal lava lizard (Microlophus bivittatus). BSc thesis, Saint John’s University, 24 pp.

- Van Denburgh J, Slevin JR (1913) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. IX. The Galapagoan lizards of the genus Tropidurus with notes on iguanas of the genera Conolophus and Amblyrhynchus. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 2: 132–202.

- Moore JA, Rowe JW, Wessels D, Plivelich MT, Valle CA (2017) Microlophus bivittatus (San Cristóbal Lava Lizard) diet. Herpetological Review 48: 851.

- Hervías-Parejo S, Heleno R, Rumeu B, Guzmán B, Vargas P, Olesen JM, Traveset A, Vera C, Benavides E, Nogales M (2018) Small size does not restrain frugivory and seed dispersal across the evolutionary radiation of Galápagos lava lizards. Current Zoology 65: 353–361. DOI: 10.1093/cz/zoy066

- Burke RL, Figueras M, Calle PP (2015) Microlophus bivittatus (lava lizard) predation. Herpetological Review 46: 632.

- Carrión PL (2012) Depredación de gatos domésticos y ferales sobre las lagartijas de lava de San Cristóbal (Microlophus bivittatus), Galápagos. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 33 pp.

- Márquez C, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2022) Microlophus bivittatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2022-1.RLTS.T48444538A217809016.en

- Marra PP, Santella C (2016) Cat Wars: the devastating consequences of a cuddly killer. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 212 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Microlophus bivittatus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Bahía Rosa Blanca | Troya Zuleta 2012 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Bahía Sardina | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cerro Brujo | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Freshwater Bay, 2 km NW of | Van Denburgh & Slevin 1913 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Galapaguera Cerro Colorado | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Galapaguera Natural (Cono Media Luna) | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Isla de Los Lobos | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Jardín de Opuntias | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Lobería | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Mirador Cerro Tijeretas | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Baquerizo | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Carola | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa de Cerro Brujo | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa La Galapaguera | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Ochoa | Troya Zuleta 2012 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Baquerizo Moreno | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Baquerizo Moreno, 3 km E of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Chino (Freshwater bay) | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Grande, 2 km SE of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Grande, 5 km SE of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Grande, 5 km SSE of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Pitt | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punto Validzán | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | San Cristobal airport | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Sappho Cove | Van Denburgh and Slevin 1913 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Wreck Bay, 1 mile inland from | Van Denburgh & Slevin 1913 |