Published March 23, 2023. Updated May 29, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Crocodylia | Alligatoridae | Melanosuchus niger

English common name: Black Caiman.

Spanish common name: Caimán negro.

Recognition: ♂♂ 4.84 mMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 2.93 mMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1–3 The Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger) is the world’s largest caiman species.4 It can be distinguished from the other two caimans inhabiting the Ecuadorian Amazon (Caiman crocodilus and Paleosuchus trigonatus) by having dark spots on the mandible and a blackish dorsal coloration with yellowish bands on the body and tail (Fig. 1).5–7 This species further differs from C. crocodilus by having flat eyelids and 4–5 rows of post-occipital plates (instead of 2–3 rows of post-occipital plates and eyelids with a triangular projection).5–7 The dwarf caiman P. trigonatus is smaller, has a chestnut iris, only one row of post-occipital plates, and lacks an inter-orbital ridge (present in M. niger).5–7

Figure 1: Individuals of Melanosuchus niger from Amazonian Ecuador: Sani Lodge, Sucumbíos province (); unknown locality (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Melanosuchus niger is a commonRecorded weekly in densities above five individuals per locality. caiman in some Amazonian localities in Ecuador, with population densities of 1–9 caimans/km, but is only about one third as abundant as the co-occurring Caiman crocodilus.8 Black Caimans are nocturnal, aquatic, and occur in a variety of slow-flowing9 freshwater habitats, including lagoons, lakes (particularly oxbow lakes), swamps, marshes, rivers, large streams, and seasonally flooded forests.4 Their home range is under 1 hectare during the low-water season and increases to 20 hectares during the rainy season.10,11 During periods of drought, individuals may remain completely embedded in the bottom mud until the rains return.9,12 Juveniles usually remain in the edges of the water bodies, surrounded by abundant floating vegetation, where they wait in ambush for prey to pass by.6,13 There is a dietary shift from invertebrate to vertebrate prey over the lifetime of M. niger.11,14 Their diet as juveniles is primarily composed of small fish, insects, arachnids, mollusks, crustaceans, and frogs.11,14,15 The diet in adults also includes these prey items,14,15 but is based primarily on fish,16 and to a smaller degree on birds, mammals (including otters,9 pacas,9 porcupines,17 agoutis,17 dogs,18,19 pigs, horses,17 and cattle16), turtles (Peltocephalus dumerilianus and Podocnemis erythrocephala,20 P. expansa,21 and P. unifilis21), smaller caimans (C. crocodilus6 as well as conspecifics17) and snakes.9,11,22 There are records of Black Caimans attacking,18,19 and even killing,23 humans.

“He [the caiman] never attacks man when his intended victim is on his guard; but he is cunning enough to know when this may be done with impunity.” “No one could descend to bathe without being advanced by one or other of these hungry monsters.”

Henry Walter Bates, British naturalist and explorer, 1864.18

Black Caimans reach sexual maturity at around 8 years old or at a length of about 2 m.4,24 Nesting in the Ecuadorian Amazon coincides with the annual low-water level season (December–January).25 Males are territorial and exclude other males from their home range.26 Females are polyandrous27 (mating with multiple males) and build ~50–80 cm tall mound-like nests using leaf-litter, twigs, roots, and decaying vegetation.16,25–29 These are located ~2–59 m from the water bodies.9,28,25 Clutches consist of 21–75 eggs that measure ~5.2–8.8 cm in length, weigh 90–155 g, and take 60–90 days to hatch.9,25–29 In Ecuador, mean hatching success is ~42% and flooding of the nests is the main cause of egg mortality (29% of all the eggs).25 Hatchlings measure ~30 cm in total length at birth.6 Juveniles remain in groups and communicate acoustically with their siblings and with the mother.25 Adults produce loud noises and grunts that can be heard over long distances.9 Females aggressively defend the nests and the hatchlings.9,25,30 Jaguars, peccaries, capuchin monkeys, opossums, coatis, mice, and tegus (Tupinambis cuzcoensis) are known predators of eggs of Melanosuchus niger.25,31–32 Otters, coatis, tayras, herons, boids (Corallus hortulana and Eunectes murinus), tegus, and piranhas are known to prey on juveniles,32 whereas jaguars are the only known predators of adults.33

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future. in Ecuador34 and Colombia.35 but listed as Least Concern globally.36 Although Melanosuchus niger is widely distributed and occurs in protected areas, the species was the subject of overexploitation for decades, particularly during the 1940s and 1950s.4,37 Uncontrolled large-scale hide hunting was the main driver of the decline,24 but so was direct killing for consumption16 or in retaliation for, or as a measure to prevent, attacks on humans, pets, or livestock.16,19,38 Although large-scale commercial exploitation of M. niger is now banned, the species is still used for other purposes.24 The meat and eggs are consumed30 and the skin is used as material for handicrafts and various garments.4,37 Some populations are still declining due to the creation of dams which force caimans into closer contact with people.39 Others are experiencing adverse effects by accumulating mercury associated with artisanal and small-scale gold mining.40 Fortunately, M. niger is now a protected species in many countries and the majority of populations appear to have recovered despite decades of overexploitation.4

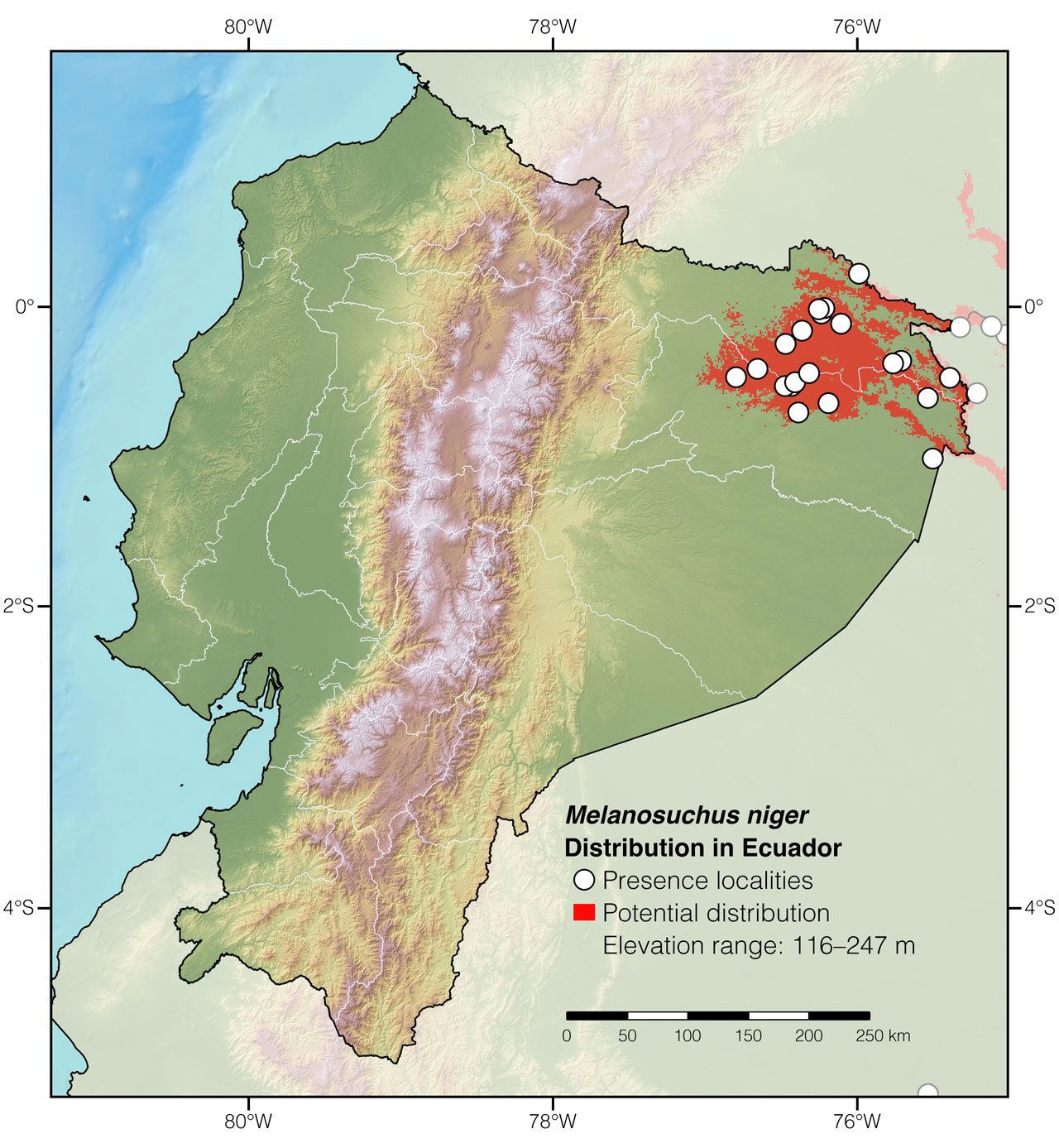

Distribution: Melanosuchus niger is widely distributed throughout the Amazon basin and peripheral areas.37 In Ecuador, the species is known only from the extreme northeastern part of the Amazon at elevations between 116 and 247 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Melanosuchus niger in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Melanosuchus is derived from the Greek words melanos (=black) and souchus (=crocodile).41 The specific epithet niger is a Latin word meaning “black.”41

See it in the wild: Black Caimans can be seen reliably in well-preserved water systems throughout the northern Ecuadorian Amazon, particularly in the following blackwater lagoons: Limoncocha, Añangu, and Challuacocha. They are most easily found at night by detecting their bright orange eye-shine. However, in most areas, individuals are becoming increasingly wary of human presence,8 fleeing when approached.

Special thanks to Nick Trapani and Debra Dabideen for symbolically adopting the Black Caiman and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Ricardo Chiriboga and María Belén Chiriboga of Zoo el Pantanal for prodiving photographic access to specimens of Melanosuchus niger under their care.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/IAHJ8674

Literature cited:

- Thorbjarnarson J, McIntosh PE (1987) Notes on a large Melanosuchus niger skull from Bolivia. Herpetological Review 18: 49–50.

- Taylor P, Li F, Holland A, Martin M, Rosenblatt AE (2016) Growth rates of black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) in the Rupununi region of Guyana. Amphibia-Reptilia 37: 9–14.

- Da Silveira R, Campos Z, Thorbjarnarson J, Magnusson WE (2013) Growth rates of black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) and spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus) from two different Amazonian flooded habitats. Amphibia-Reptilia 34: 437–449.

- Thorbjarnarson JB (2010) Black Caiman Melanosuchus niger. In: Manolis SC, Stevenson C (Eds) Crocodiles: status survey and conservation action plan. Crocodile Specialist Group, Darwin, 29–39.

- Brazaitis P (1973) The identification of living crocodilians. Scientific Contributions of the New York Zoological Society 58: 59–101.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, De La Ossa V J, Fajardo-Patiño A (2013) Biología y conservación de los Crocodylia de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros Continentales de Colombia, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Bogotá, 335 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Ortiz Yépez DA (2012) Estudio poblacional de caimanes (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae) en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana. BSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 87 pp.

- Medem F (1963) Osteología craneal, distribución geográfica y ecología de Melanosuchus niger (Spix) (Crocodylia, Alligatoridae). Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 45: 5–20.

- De la Quintana P, Aparicio J, Pacheco LF (2020) Home range and habitat use of two sympatric crocodylians (Melanosuchus niger and Caiman yacare) under changing habitat conditions. Amphibia-Reptilia 42: 1–9. DOI: 10.1163/15685381-bja10027

- Caut S, Francois V, Bacques M, Guiral D, Lemaire J, Lepoint G, Sturaro N (2019) The dark side of the black caiman: shedding light on species dietary ecology and movement in Agami Pond, French Guiana. PLoS ONE 17: e0217239. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217239

- Hagmann G (1910) Die Reptilien del Insel Mexiana, Amazonenstrom. Zoologische Jahrbücher 28: 473–504.

- Da Silveira R, Magnusson WE, Campos Z (1997) Monitoring the distribution, abundance, and breeding areas of Caiman crocodilus crocodilus and Melanosuchus niger in the Anavilhans Archipelago, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Journal of Herpetology 31: 514–520.

- Horna JV, Cintra R, Ruesta PV (2001) Feeding ecology of black caiman Melanosuchus niger in a western Amazonian forest: the effects of ontogeny and seasonality on diet composition. Ecotropica 7: 1–11.

- da Silveira R, Magnusson WE (1999) Diets of spectacled and black caiman in the Anavilhanas Archipelago, central Amazonia, Brazil. Journal of Herpetology 3: 181–192.

- Cott HB (1926) Observations on the life habits of some batrachians and reptiles from the lower Amazon: and a note on some mammals from Marajó Island. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 96: 1159–1178. DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1926.tb02240.x

- Rosenblatt AE, Li F, Kalicharan L, Taylor P (2021) What do adult black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) actually eat? Biotropica 54: 275–278. DOI: 10.1111/btp.13038

- Bates HW (1864) The naturalist on the River Amazons, with an appreciation by Charles Darwin. Everyman’s Library, London & New York, 407 pp.

- Hall P (1991) Dangerous to man? A record of an attack by a black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) in Guyana. Herpetological Review 22: 9–11.

- de la Ossa-Velásquez J, Vogt RC, Ferrara CR (2010) Melanosuchus niger (Crocodylia: Alligatoridae) as opportunistic turtle consumer in its natural environment. Revista Colombiana de Ciencia Animal 2: 244–252.

- Salera Junior G, Malvasio A, Portelinha TC (2009) Evaluation of predation in Podocnemis expansa and Podocnemis unifilis (Testudines, Podocnemididae) in the Javaés River, Tocantins. Acta Amazonica 39: 197–204. DOI: 10.1590/S0044-59672009000100022

- Magnusson WE, da Silva EV, Lima AP (1987) Diets of Amazonian Crocodilians. Journal of Herpetology 21: 85–89.

- Pooley S, Siroski PA, Fernandez L, Sideleau B, Ponce-Campos P (2021) Human–crocodilian interactions in Latin America and the Caribbean region. Conservation Science and Practice 3: e351. DOI: 10.1111/csp2.351

- Plotkin MJ, Medem F, Mittermeier RA, Constable ID (1983) Distribution and conservation of the black caiman (Melanosuchus niger). In: Rhodin AGJ, Miyata K (Eds) Advances in herpetology and evolutionary biology: essays in honor of Ernest E Williams. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, 695–705.

- Villamarín-Jurado F, Suárez E (2007) Nesting of black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) in northeastern Ecuador. Journal of Herpetology 41: 164–167.

- Da Silveira R (2002) Conservação e manejo do jacaré açu (Melanosuchus niger) na Amazônia Brasileira. In: Verdade LM, Larriera A (Eds) La conservación y el manejo de caimanes y cocodrilos de América Latina. CN Editora, São Paulo, 61–78.

- Muniz FL, Da Silveira R, Campos Z, Magnusson WE, Hrbek T, Farias IP (2011) Multiple paternity in the Black Caiman (Melanosuchus niger) population in the Anavilhanas National Park, Brazilian Amazonia. Amphibia-Reptilia 32: 428–434.

- Herron JC, Emmons LH, Cadle JE (1990) Observations on reproduction in the Black Caiman, Melanosuchus niger. Journal of Herpetology 24: 314–316.

- Hagmann G (1902) Die Eier von Caiman niger. Zoologische Jahrbücher 16: 405–410.

- Torralvo K, Botero-Arias R, Magnusson WE (2017) Temporal variation in black-caiman nest predation in varzea of central Brazilian Amazonia. PLoS ONE 12: e0183476. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183476

- Torralvo K, Rabelo RM (2018) Melanosuchus niger (Black Caiman) and Caiman crocodilus (Spectacled Caiman): nesting. Herpetological Review 49: 113–114.

- Asanza E (1985) Distribución, biología reproductiva y alimentación de cuatro especies de Alligatoridae, especialmente Caiman crocodilus, en la Amazonía del Ecuador. BSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 145 pp.

- Da Silveira R, Ramalho EE, Thorbjarnarson JB, Magnusson WE (2010) Depredation by jaguars on caimans and importance of reptiles in the diet of jaguar. Journal of Herpetology 44: 418–424. DOI: 10.1670/08-340.1

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Ross JP (2010) Melanosuchus niger. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2000.RLTS.T13053A3407604.en

- Ross JP (1998) Crocodiles: status survey and conservation action plan. IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, Gainesville, 97 pp.

- Pierre MA, Jacobsen KS, Hallett MT, Harris AE, Melville A, Barnabus H, Sillero-Zubiri C (2021) Drivers of human–black caiman (Melanosuchus niger) conflict in indigenous communities in the North Rupununi wetlands, southwestern Guyana. Conservation Science and Practice 5: e12848. DOI: 10.1111/csp2.12848

- Campos Z (2015) Size of caimans killed by humans at a hydroelectric dam in the Madeira River, Brazilian Amazon. Herpetozoa 28: 101–104.

- Lemaire J, Bustamante P, Marquis O, Caut S, Brischoux F (2021) Influence of sex, size and trophic level on blood Hg concentrations in Black Caiman, Melanosuchus niger (Spix, 1825) in French Guiana. Chemosphere 262: 127819. DOI: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127819

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Melanosuchus niger in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Caño Concepción | Medem 1963 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Leguízamo | Alonso González & Augusto Bonilla 2008 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Caucaya | WWF 2010 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | Medem 1963 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bodega NPW | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Laguna Taracoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Napo Wildlife Center | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Rio Tiputini, near YCS | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Bloque 15 | Izquierdo et al. 2000 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Canangüeno | Ortiz 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Tsiaya | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Zábalo | Cevallos Bustos 2010 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | FMNH 2008 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Heron Lake | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago El Charo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande de Cuyabeno | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Mateococha | Ortiz 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Payaguaje | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Reserva Biológica Limoncocha | Villamarín 2006 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Güeppi | Yanez-Muñoz et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Zábalo camp | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Observation by AA |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Zancudococha | Dueñas 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pacaya Samiria National Reserve | Verdi et al. 1980 |

| Perú | Loreto | Redondococha | FMNH 2008 |