Published November 4, 2020. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Chocoan Bushmaster (Lachesis acrochorda)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Lachesis acrochorda

English common names: Chocoan Bushmaster.

Spanish common names: Verrugosa de la costa, guascama (Ecuador); mapaná rayo, verrugoso, walkauna (Colombia); verrugosa (Panama).

Recognition: ♂♂ 243 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 234.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. In its area of distribution, the Chocoan Bushmaster (Lachesis acrochorda) can be identified by having the following combination of features: heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, a snout that is not upturned, an arabesque pattern of 23–31 contrasting dark-brown to black blotches on a light orangish-brown dorsum, and prominent knoblike keels on the dorsal scales that give the snake a “pineapple texture.”1,2 The only other viper in western Ecuador having knoblike keels on the dorsal scales is Bothrocophias campbelli, a snake that can easily be identified based on its upturned snout.3

Figure 1: Individuals of Lachesis acrochorda from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador (); Mashpi Reserve, Pichincha province, Ecuador (); and Morromico, Chocó department, Colombia (). ad=adult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: RareTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than ten. to extremely rareTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than three.. Lachesis acrochorda is a terrestrial snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen lowland and foothill forests (rainforests).4 The species generally requires more pristine and remote habitats than other vipers in the Chocó region.4,5 Chocoan bushmasters have been seen active at night as well as during the daytime.4 They spend most of their time coiled on the forest floor close to vegetation cover, usually along streams, steep banks, or at the entrance of mammal burrows.1,4,6 When not active, snakes of this species hide inside hollow logs.7

Chocoan Bushmasters are ambush predators.1 Their diet includes rodents8 and presumably other small mammals. Individuals of Lachesis acrochorda rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism. Unlike popular belief, these vipers are not aggressive, but calm and sluggish when confronted.1,7 In the presence of a disturbance, most individuals try to flee or emit a low whistle-like sound,1 but others will readily bite if attacked or harassed.

“They say that once the traveler has positioned himself within his (a Chocoan Bushmaster’s) radius of attack, the serpent and the man come face-to-face, resolving the problem of life or death. If the man does not have a gun in his hand, he better resolve to strangle the monster, gripping it with athletic force by the throat, and any companion, maintain his grasp among the spirals of the snake, which will not delay in wrapping itself, such that one is obliged to loosen its coils. Overall this may contain some grain of truth; but also a lot of fantasy and marvel.”

Evaristo García, Colombian physician and researcher, 1896.2

Lachesis acrochorda is a venomous species (LD50 4.9–14 mg/kg)9,10 that is responsible for 0.7–2.9% of snakebites in some areas of its range.11,12 In humans, bites of this species, although infrequent, typically cause pain, nausea, vertigo, low blood pressure, swelling, intense bleeding, defibrination (depletion of the blood’s coagulation factors), and necrosis (death of tissues and cells).10,11,13 In poorly managed or untreated cases, the venom can cause intracranial hemorrhage, shock, renal disturbances, permanent sequelae, and (in 90% of cases that are not properly attended)14 death.15 The prognosis is usually bad for victims that reach a hospital over 12 hours after the bite and for those that resort to traditional medicine.15

What to do if you are bitten by a Chocoan Bushmaster?

|

Reproduction in Lachesis acrochorda seems to take place year-round.6 In captivity, one male courted a female for 15 days.5 After a gestation period of 110 days (~3.6 months),5 females lay 5–14 eggs in burrows (of agoutis and armadillos), but they do not provide significant parental care to the clutch.5,6,8 The egg’s incubation period is 70–96 days (~2.3–3 months).5,6 Neonates measure 36.1–47.5 cm.5,6 Under human care, individuals can live up to ~18 years,1 and probably much longer.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Lachesis acrochorda is here proposed to be assigned in this category following IUCN criteria16 because the species is widely distributed throughout the lowlands of the Chocó and Río Magdalena valley regions,2 especially in areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, such as the Colombian Pacific coast. As a result, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. Unfortunately, Chocoan Bushmasters suffer from direct killing6 and habitat loss,5 especially in Ecuador, where an estimated17 ~59.7% of the habitat of the species has been destroyed.

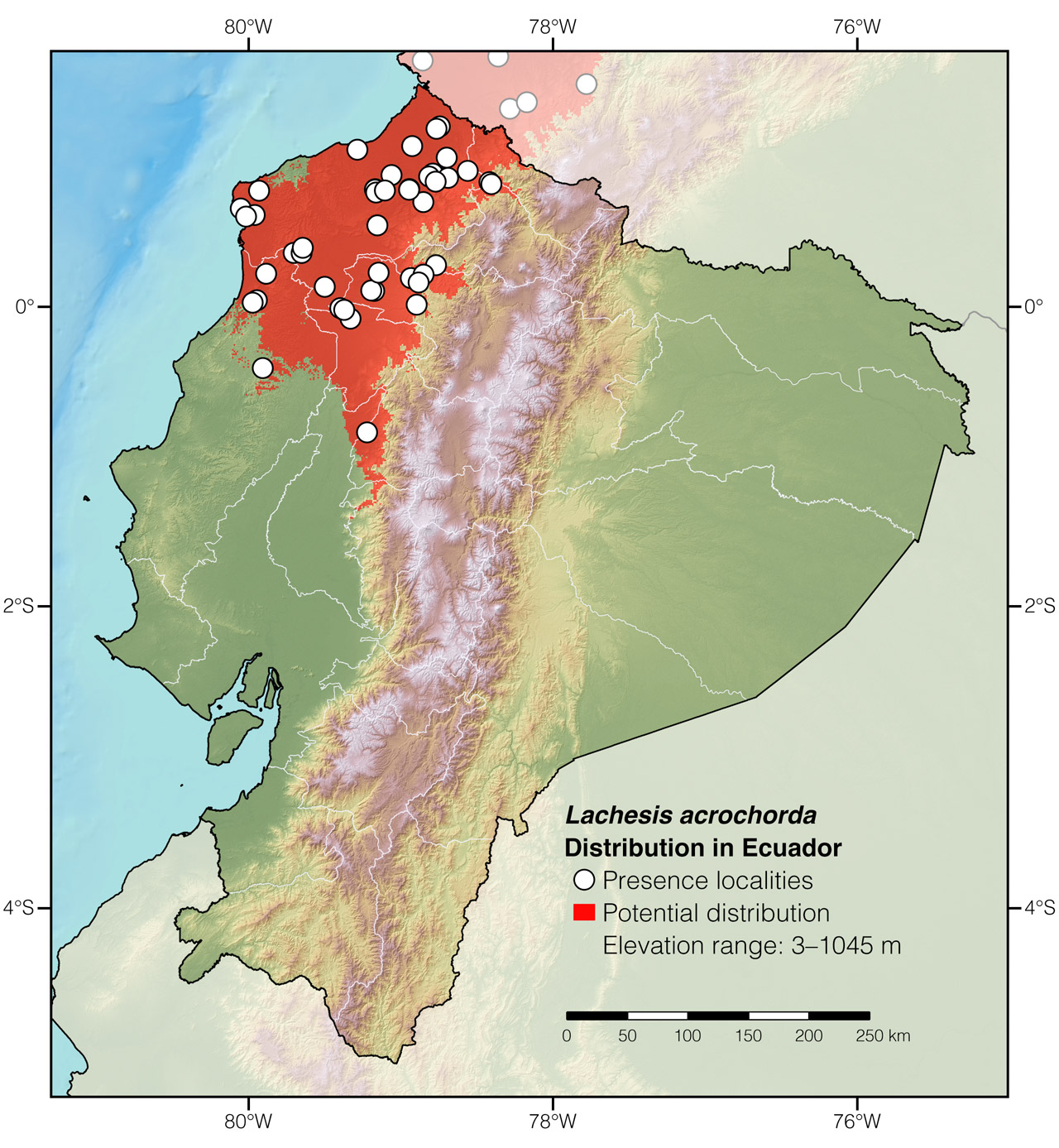

Distribution: Lachesis acrochorda is native to the lowlands and adjacent mountain foothills of the Chocó and Río Magdalena valley regions from eastern Panamá, through Colombia, to northwestern Ecuador. In Ecuador, the species occurs at elevations between 3 and 1045 m.

Figure 2: Distribution of Lachesis acrochorda in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Lachesis is derived from the name of one of the “Three Fates” (also known as Moirae or incarnations of destiny) in Greek mythology.2 Lachesis was the Moira that decided the length of life allotted to each human being and god.2 This epithet was probably given to reflect the feeling of having one’s fate at the mercy of the snake upon encountering such an imposing creature.18 The specific epithet acrochorda, which is derived from the Greek word akrochordon (meaning “wart”), refers to the knoblike keels on the dorsal scales.2

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Chocoan Bushmasters are recorded rarely, usually no more than once every few months at any given locality. However, there are some areas, like in Mashpi Lodge and Canandé Reserve, where individuals are seen more frequently, albeit certainly not reliably. The snakes may be located by walking along trails or by cruising roads through primary forest.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Carlos Robles, Darwin Núñez, David Salazar, Elson Meneses-Pelayo, Konrad Mebert, Pablo Loaiza, and Regdy Vera for providing natural history information and locality records for Lachesis acrochorda.

Special thanks to Nicola Paganuzzi and Nicolas Betancourt for symbolically adopting the Chocoan Bushmaster and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di Doménico.cAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Chocoan Bushmaster (Lachesis acrochorda). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/SDLV8376

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Henao Duque AM, Corrales G (2015) First report of the reproduction in captivity of the Chocoan Bushmaster, Lachesis acrochorda (García, 1896). Herpetology Notes 8: 315–320.

- Fuentes RD, Corrales G (2016) New distribution record and reproductive data for the Chocoan Bushmaster, Lachesis acrochorda (Serpentes: Viperidae), in Panama. Mesoamerican Herpetology 3: 115–127.

- Konrad Mebert, pers. comm.

- Elson Meneses-Pelayo, pers. comm.

- Kuch U, Mebs D, Gutiérrez JM, Freire A (1996) Biochemical and biological characterization of the Ecuadorian pitvipers (genera Bothriechis, Bothriopsis, Bothrops, and Lachesis). Toxicon 34: 714–717. DOI: 10.1016/0041-0101(96)00016-5

- Otero R, Furtado MFD, Gonçalves LR, Núñez V, García ME, Osorio RG, Romero M, Gutiérrez JM (1998) Comparative study of the venoms of three subspecies of Lachesis muta (bushmaster) from Brazil, Colombia and Costa Rica. Toxicon 36: 2021–2027. DOI: 10.1016/s0041-0101(98)00089-0

- Sevilla-Sánchez MJ, Mora-Obando D, Calderón JJ, Guerrero-Vargas JA, Ayerbe-González S (2019) Accidente ofídico en el departamento de Nariño, Colombia: análisis retrospectivo, 2008–2017. Biomédica 39: 715–736. DOI: 10.7705/biomedica.4830

- Touzet JM (1998) La endemia ofidiana en Ecuador, estudio de caso: accidentes ofídicos en las provincias de Esmeraldas y Manabí. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito.

- Otero R, Osorio RG, Valderrama R, Giraldo CA (1992) Efectos farmacológicos y enzimáticos de los venenos de serpientes de Antioquia y Chocó (Colombia). Toxicon 30: 611–620. DOI: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90855-Y

- Angel-Camilo KL, Guerrero-Vargas JA, Carvalho EF, Lima-Silva K, de Siqueira RJB, Freitas LBN, Sousa JAC, Mota MRL, Santos AAD, Neves-Ferreira A, Havt A, Leal L, Magalhaes PJC (2020) Disorders on cardiovascular parameters in rats and in human blood cells caused by Lachesis acrochorda snake venom. Toxicon 184: 180–191. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.06.009

- Otero R, Tobón GS, Gómez LF, Osorio R, Valderrama R, Hoyos D, Urreta JE, Molina S, Arboleda JJ (1992) Accidente ofídico en Antioquia y Chocó. Acta Médica Colombiana 17: 229–249.

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Diniz-Sousa R, Moraes JN, Rodrigues-da-Silva TM, Oliveira CS, Caldeira CAS (2020) A brief review on the natural history, venomics and the medical importance of bushmaster (Lachesis) pit viper snakes. Toxicon 7: 1–12. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxcx.2020.100053

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Lachesis acrochorda in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Cumilinche | Photo by Juan Carvajal |

| Colombia | Nariño | El Pangán | Photo by Juan Carlos Luna |

| Colombia | Nariño | El Vergel | Sevilla-Sánchez et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Laguna El Placer, environs of | Sevilla-Sánchez et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Somewhere in Barbacoas | Sevilla-Sánchez et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | El Jardín de los Sueños | Photo by Christophe Pellet |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Reserve | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cachabi | USNM 165008 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Centro de Fauna Silvestre James Brown | Photo by Salvador Palacios |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Comunidad Loma Linda | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | El Aguacate | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Gualpí | Morales-Mite 2002 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Gualpí de Onzole | Valencia et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Equinox | USNM 237086 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | km 17 Lita–Alto Tambo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Tabla | Morales-Mite 2002 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Las Mareas | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Lote Salvadores | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Macará | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Majúa, Río Cayapas | MCZ 11169 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Maldonado | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Mayronga, Lagarto | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Muisne | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Near Río Cayapas | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Padre Santo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Pajonal | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Playa de Oro | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Pote | Morales-Mite 2002 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Salto del Bravo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo–Lita | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tangareal | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tesoro Escondido | Reserva Tesoro Escondido |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma | Pablo Loaiza, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Y de la Laguna | Ítalo Tapia, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Zapallo Grande | MHNG 2458.046 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Finca Agroecológica Los Robles | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Lita | MHNG 2528.067 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Los Cedros | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Flavio Alfaro | MHNG 2511.097 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Hacienda Siberia | Hamilton et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | km 16 Pedernales–El Carmen | David Salazar, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Lower Pata de Pájaro | Carlos Robles, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Between Mashpi and Yurimagua | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | El Chalpi-Saguangal | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rainforest Monterreal | Photo by Jorge Ambuludi |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rancho Suamox | Photo by Rafael Ferro |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Selva Virgen | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Unidos Venceremos | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Hacienda El Cortejo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | La Evelina | Photo by Salvador Palacios |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | La Perla | Photo by Paul Hamilton |