Published January 6, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Scorpion Mud Turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Kinosternidae | Kinosternon scorpioides

English common name: Scorpion Mud Turtle.

Spanish common names: Taparrabo escorpión, tortuga taparrabo de la Amazonía (Ecuador); tortuga estuche, tortuga candado, tortuga tapaculo (Colombia).

Recognition: ♂♂ 20.5 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 19.5 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace..1 The Scorpion Mud Turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides) can be distinguished from K. leucostomum based on having three longitudinal dorsal keels (Fig. 1) on the carapace and a plastron that when closed leaves hind legs barely visible rather than fully concealed.2–4 The plastron is mobile, with two well-developed hinges that create a tight closure to protect the body of the animal.4,5 The head is grayish brown with pale brown spots and the maxilla is strongly hooked with three or four pairs of barbels.6 Males have a slightly more concave plastron, bigger head, and a considerably longer tail with a much larger terminal spine than females.4,7 Females tend to have more domed carapace and a larger plastron than males.8 Kinosternon scorpioides differs from turtles of the Chelidae family by having a dome-shaped carapace and hinged plastron.6

Figure 1: Individuals of Kinosternon scorpioides from Lago Agrio, Sucumbíos province, Ecuador. ad=adult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Kinosternon scorpioides is an uncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months. species in Ecuador9 and Peru,3,10 but has high population densities in other areas. Densities of up to 254–316.5 individuals/hectare have been estimated in Colombia,11 México,12 and Costa Rica.13 This species occurs in and nearby a wide variety of permanent to temporary aquatic environments, primarily ponds, lakes, and swamps, but also streams and rivers.4,6,14 Individuals are also occasionally seen crossing roads, trails, and grass fields as far as 500 m from the nearest water body.3,4,15 These turtles are benthic walkers rather than swimmers16 and are mainly restricted to freshwater, although individuals have been recorded in brackish conditions in Costa Rica.4,17 They are active during the day and at night.2,4 In seasonally dry areas (not in Ecuador), individuals bury themselves in dry mud or leaf-litter where they remain dormant during times of drought.4 The diet of K. scorpioides is primarily carnivorous and includes insects, crustaceans, worms, snails, fish, frogs, and carrion, but also algae, fruits, seeds, flowers, and aquatic plants.2,4,18 Adult turtles of this species are preyed upon by coyotes, jaguars and other felines; juveniles by coyotes, cats, raptors, vultures, and other turtles.4 Although usually shy, when handled these turtles can bite.15 They also have musk glands that expel a fetid odor as defense.2

Scorpion Mud Turtles reach their sexual maturity at around 20 months old or when females attain a straight carapace length of 10 cm; males at 9.4 cm.19 The nesting season extends for up to 10 months a year and females are able to produce multiple annual clutches.4 Copulation takes place on land or in shallow water and egg laying takes place quickly after copulation.4 Females create shallow nests up to 191 m from bodies of water and cover them with masses of herbs or shrubs.2,4 Clutch size is between 1 and 8 eggs and each one is 23–41 mm long, 14–26 mm wide, and weighs 2.5–11.8 g.4,20 Incubation time is 115–128 days or roughly 4 months.16 Temperature during incubation determines the sex of the hatchlings: low and high temperatures produces females and mid-temperatures result in males.4,21 The maximum recorded lifespan of turtles of this species is 26 years.22

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..23,24 Kinosternon scorpioides is included in this category given its wide distribution throughout Central and South America, especially over areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, such as the Amazon basin. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. However, some populations are declining due to habitat degradation, anthropogenic pollution, and indiscriminate harvesting.4 Adult turtles are hunted for consumption,10 medicinal use, or to be used or sold as pets.4

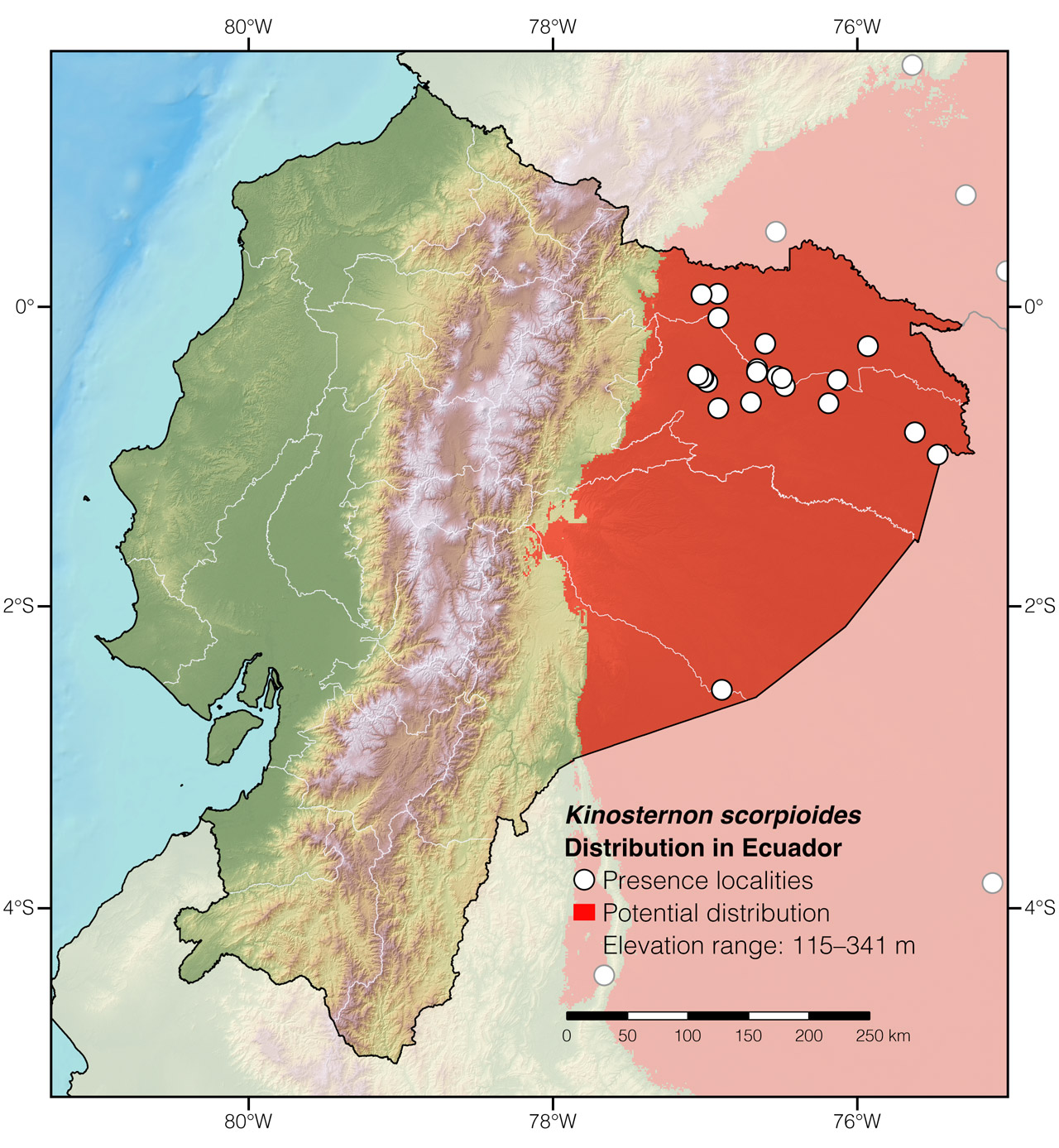

Distribution: Kinosternon scorpioides is native to an estimated area of 7,778,398 km2 throughout much of the Neotropical region, from México to northern Argentina.1 In Ecuador, the species occurs on the Amazon lowlands at elevations between 115 and 341 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Kinosternon scorpioides in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Kinosternon, which comes from the Greek words kinetos (meaning “movable”) and sternon (meaning “chest”),25 refers to the hinged plastron. The specific epithet scorpioides, which is derived from the Latin word scorpio (a scorpion) and oides (meaning “similar to”),25 refers to the horny spine on the tail-tip.26

See it in the wild: In Amazonian Ecuador, individuals of Kinosternon scorpioides are unlikely to be seen more than once every few months at any given locality, and then usually just by chance. Since they are semi-aquatic, Scorpion Mud Turtles are most easily located by walking along the shores of muddy water bodies. In Ecuador, the greatest number of observations of K. scorpioides are in Yasuní National Park.

Authors: Gabriela SandovalaAffiliation: Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Sandoval G, Arteaga A (2023) Scorpion Mud Turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/SDCB9003

Literature cited:

- Rhodin AGJ, Iverson JB, Bour R, Fritz U, Georges A, Shaffer HB, van Dijk PP (2021) Turtles of the world: annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Chelonian Research Monographs 8: 1–472. DOI: 10.3854/crm.8.checklist.atlas.v9.2021

- Rueda-Almonacid JV, Carr JL, Mittermeier RA, Rodríguez-Mahecha JV, Mast RB, Vogt RC, Rhodin AGJ, de la Ossa-Velásquez J, Rueda JN, Mittermeier CG (2007) Las tortugas y los cocodrilianos de los países andinos del trópico. Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, 538 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Berry JF, Iverson JB (2011) Kinosternon scorpioides (Linnaeus 1766) – Scorpion Mud Turtle. Chelonian Research Monographs 5: 1–15. DOI: 10.3854/crm.5.063.scorpioides.v1.2011

- Iverson JB (1991) Phylogenetic hypotheses for the evolution of modern kinosternine turtles. Herpetological Monographs 4: 1–27. DOI: 10.2307/1466974

- Berry JF, Iverson J, Forero-Medina G (2012) Kinosternon scorpioides. In: Páez VP, Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Castaño-Mora OV, Bock BC (Eds) Biología y conservación de las tortugas continentales de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros Continentales de Colombia, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Bogotá, 340–348.

- Pritchard PCH, Trebbau P (1984) Turtles of Venezuela. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, 403 pp.

- Berry JF, Iverson J (2001) Kinosternon scorpioides (Linnaeus) Scorpion Mud Turtle. Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles 725: 1–11.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Forero-Medina G, Castaño-Mora OV (2006) Kinosternon scorpioides albogulare (White-throated mud turtle): feeding behavior and diet. Herpetological Review 37: 458–459.

- Iverson JB (1982) Biomass in turtle populations: a neglected subject. Oecologia 55: 69–76. DOI: 10.1007/BF00386720

- Guinn JE, Luger P (2011) Reading the ashes: arson decimates a tropical wetland, but allows new observations of a neotropical mud turtle. Reptiles & Amphibians 18: 34–38.

- Medem F (1958) El conocimiento actual sobre la distribución geográfica de las Testudinata en Colombia. Boletín del Museo de Ciencias Naturales, Caracas 2: 13–45.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Acuña RA, Castaing A, Flores F (1984) Aspectos ecológicos de la distribución de las tortugas terrestres y semiacuáticas en el Valle Central de Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical 31: 181–192. DOI: 10.15517/rbt.v31i2.24932

- Carvalho Jr EAR, Paschoalini EL (2008) Diet of Kinosternon scorpioides in Serra dos Carajas, eastern Amazonia. Herpetological Review 39: 283–285.

- Barreto L, Lima LC, Barbosa S (2009) Observations on the ecology of Trachemys adiutrix and Kinosternon scorpioides on Curupu Island, Brazil. Herpetological Review 40: 283–286.

- Iverson JB (2010) Reproduction on the Red-cheeked Mud Turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides cruentatum) in southeastern Mexico and Belize, with comparisons across the species range. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 9: 250–261. DOI: 10.2744/CCB-0827.1

- Ewert MA, Nelson CE (1991) Sex determination in turtles: diverse patterns and some possible adaptive values. Copeia 1991: 50–69. DOI: 10.2307/1446248

- Slavens FL, Slavens K (1994) Reptiles and amphibians in captivity: breeding, longevity, and inventory. Slaveware, Seattle, 522 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Lemos-Espinal JA, Dixon JR (2013) Amphibians and reptiles of San Luis Potosí. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, 312 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Kinosternon scorpioides in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Río Caquetá | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Río Yari | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Tres Esquinas | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Delicias | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Berry et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bloque 43 | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca, 4 km SE Ecuador | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca, Gran Hotel de Lago | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dayuma | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Edén | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | ZMH R03856; not examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca, Hotel Amazónico | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Napo Wildlife Center | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pompeya, 1.5 km N of | Observation by Alejandro Arteaga; this work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Puerto Providencia | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini, near Mandaripanga Lodge | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sendero Pumañambi | Photo of QCAZ 11595 in Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | Photo by Kristiina Ovaska |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad San Victoriano | QCAZ 515 (not examined); Torres-Carvajal et al. (2019) |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Eno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Photo by John Castillo |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | UIMNH 62854; not examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | Photo by Roy Averrill |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi, 9 km SE of | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Amazonas | Arutam | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Teniente Pinglo | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Loreto | San Antonio de Yanayacu | Venegas et al. 2014 |

| Perú | Loreto | Santa Teresa | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Loreto | Trompeteros | Rhodin et al. 2021 |