Published November 14, 2020. Updated April 24, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Aesculapian False-Coralsnake (Erythrolamprus aesculapii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Erythrolamprus aesculapii

English common names: Aesculapian False-Coralsnake, South American False Coralsnake, Common False Coralsnake.

Spanish common names: Falsa coral medicinal, falsa coral misionera.

Recognition: ♂♂ 76.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 103.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1,2 Erythrolamprus aesculapii is distinguished from the true coralsnakes (genus Micrurus) that inhabit Ecuador by having eyes that are considerably (3.6–6 times) larger than the adjacent preocular scale, whereas in coralsnakes the eye is about the same size as the preocular scale. Amazonian populations of E. aesculapii differ from other species of the genus by having black rings arranged in pairs rather than in triads or monads (such as in E. guentheri).3 The color pattern of E. aesculapii is both aposematic (serving to warn or repel predators) and mimetic (Fig. 1), resembling venomous snakes of the genus Micrurus,4 particularly M. helleri. In Ecuador, young individuals of E. aesculapii usually have a distinct bright orange band across the parietals.

Figure 1: Individuals of Erythrolamprus aesculapii from Ecuador: Gareno, Napo province (); Yarina Lodge, Orellana province ().

Natural history: Erythrolamprus aesculapii is a rarely seen diurnal/crepuscular and terrestrial snake found in old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen lowland/foothill forests (rainforests) and forested environments in savanna ecosystems (in Brazil and Paraguay).5–8 The species also occurs in plantations,9 pastures, rural gardens,10 and occasionally inside houses. Most active individuals are seen during the day or at dusk, foraging on the forest floor,5,11 crossing roads and trails, and swimming across bodies of water.12–14 When not active, individuals hide underground.15

Aesculapian False-Coralsnakes are active hunters. They search for prey in open areas as well as in shelters.5 Their diet is based mostly on long-bodied prey such as snakes (including Atractus occipitoalbus,11 A. torquatus,1 Dipsas catesbyi,16 Ninia atrata, Erythrolamprus taeniogaster, E. typhlus, Leptodeira annulata, Oxyrhopus petolarius, Xenodon severus),5,17,18 lizards (such as Ameiva ameiva),19,20, fish (particularly swamp eels of the genus Synbranchus),15 and earthworms. Insects are probably consumed though secondary ingestion.15 The diet seems to shift from being based primarily on lizard prey as juveniles to based mostly on snakes as adults.20 Unlike most ophiophagous (feeding on snakes) serpents,17 individuals of E. aesculapii ingest prey tail-first.2

Aesculapian False-Coralsnakes rely on their warning coloration as a primary defense mechanism. Individuals are usually calm15 and try to flee when threatened.21 If disturbed, they may flatten their body dorsoventrally, hide the head, expose the hemipenes,22 and curl and display their bright tails as a decoy in a way similar to the behavior of true coralsnakes.4,23 They are also capable of striking if provoked.24 Individuals of Erythrolamprus aesculapii are opisthoglyphous (having enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla) and mildly venomous (LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 9.5 mg/kg).25,26 Their venom resembles that of vipers rather than that of coralsnakes.26 It is composed mainly of tissue-damaging toxins that paralyze small prey and can be dangerous to humans.26,27 People bitten by E. aesculapii experience pain, swelling, and bleeding at the bite site.27,28

Females of Erythrolamprus aesculapii become sexually mature when they reach ~63.5 cm in snout-vent length; males at ~43 cm.18 Clutch size ranges from one to eight eggs.5,18,22 Despite the seasonality in some areas where E. aesculapii occurs, the reproductive cycle of the species is continuous throughout the year.18 However the follicles and eggs are larger during the rainy season.18,24 Females can produce multiple clutches as a result of a unique copulation event.18 Little is known about the predators of Aesculapian False-Coralsnakes. Anecdotal observations suggest that they are preyed upon by hawks.29 Captive individuals of E. aesculapii are parasitized by nematodes.30

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..31 Erythrolamprus aesculapii is listed in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas, and presumed stable populations.31 However, the destruction and fragmentation of forested environments throughout South America can be a threat for the long-term of survival of the species.32 Individuals of E. aesculapii also suffer from traffic mortality33 and direct killing.21 Aesculapian False-Coralsnakes are often mistaken with true coralsnakes and therefore killed on sight.21

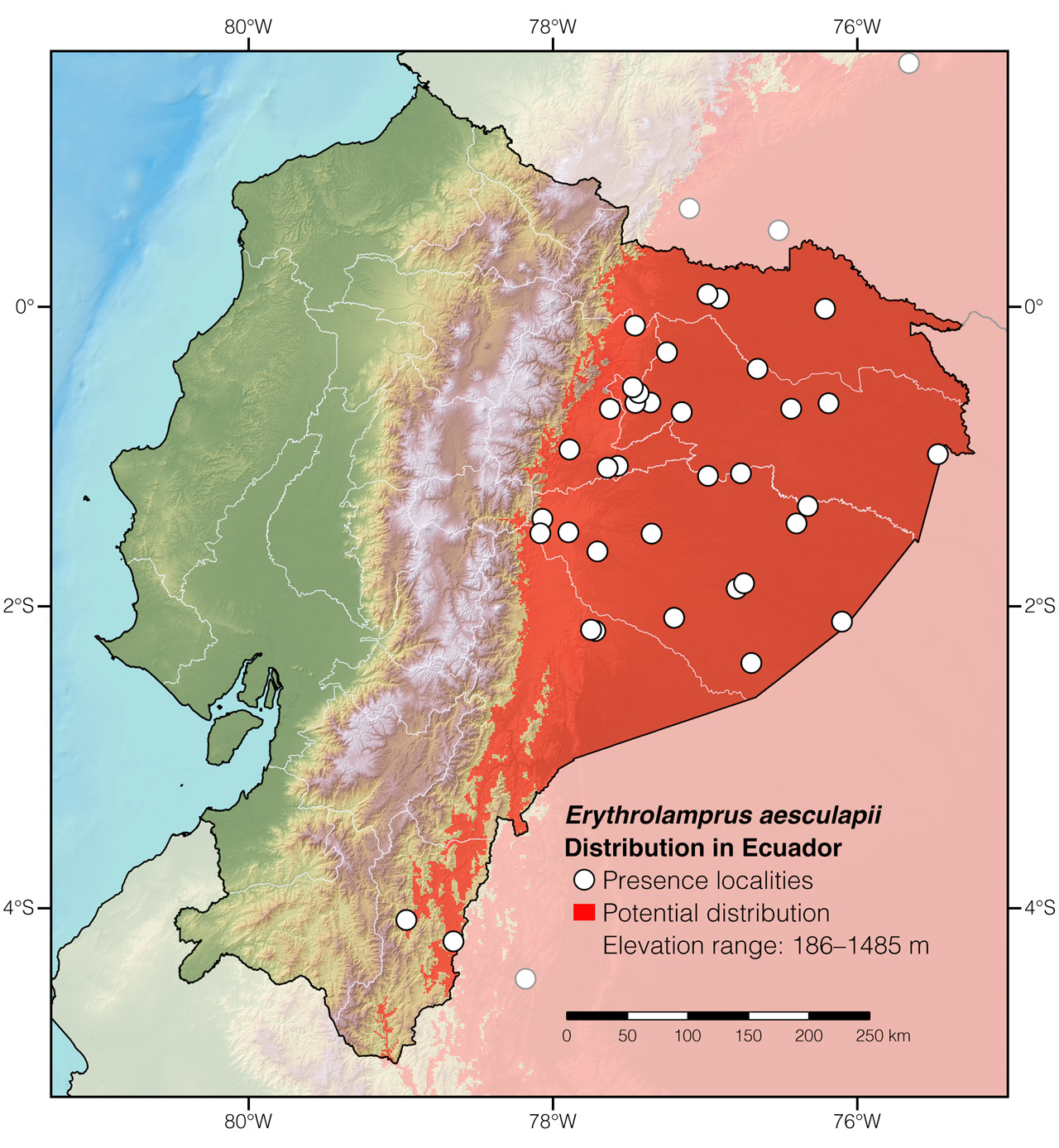

Distribution: Erythrolamprus aesculapii is native to an estimated ~1,956,115 km2 area throughout the Amazon basin and adjacent foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela. The species also occurs in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, in the Brazilian Cerrado, and El Chaco plains in Argentina and Paraguay.6 However, as currently understood, E. aesculapii is a species complex rather than a single species.34

Figure 2: Distribution of Erythrolamprus aesculapii in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Erythrolamprus, which comes from the Greek words erythros (=red) and lampros (=brilliant),35 refers to the bright red body rings of some snakes in this genus. The specific epithet aesculapii refers to Asklepios, the Ancient Greek god of medicine.36 Asklepios carried a staff with several snakes wrapped around it.

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Aesculapian False-Coralsnakes cannot be expected to be seen reliably using standard methods of field herping, since individuals are recorded accidentally and no more than once every few months.

Acknowledgments: The first author would like to thank Caroline Guevara-Molina for the comments and suggestions that enhanced the scientific quality of this work. The second author would like to thank Diego Piñán for pointing out the location of the specimen of Erythrolamprus aesculapii photographed in this account.

Special thanks to David Manning for symbolically adopting the Aesculapian False-Coralsnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Juan C. Díaz-RicaurteaAffiliation: Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Amanda QuezadabAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Díaz-Ricaurte JC, Arteaga A (2024) Aesculapian False-Coralsnake (Erythrolamprus aesculapii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/UAKM7132

Literature cited:

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Braz HB, Marques OAV (2016) Tail-first ingestion of prey by the false coral snake, Erythrolamprus aesculapii: does it know where the tail is? Salamandra 52: 211–214.

- Curcio FF, Scali S, Rodrigues MT (2015) Taxonomic status of Erythrolamprus bizona Jan (1863 (Serpentes, Xenodontinae): assembling a puzzle with many missing pieces. Herpetological Monographs 29: 40–64. DOI: 10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-15-00002

- Marques OAV, Puorto G (1991) Padrões cromáticos, distribuição e possível mimetimo em Erythrolamprus aesculapii (Serpentes, Colubridae), no sudeste do Brasil. Memórias do Instituto Butantan 53: 127–134.

- Hartmann PA (2005) História natural e ecologia de duas taxocenoses de serpentes na Mata Atlântica. PhD thesis, Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho,” 116 pp.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Sazima I, Haddad CFB (1992) Répteis da Serra do Japi: notas sobre história natural. In: Morellato LPC (Ed) História natural da Serra do Japi: ecologia e preservação de uma área florestal no Sudeste do Brasil. Editora da Unicamp/FAPESP, Campinas, 212–236.

- Marques OAV, Eterovick A, Sazima I (2001) Serpentes da Mata Atlântica: guia ilustrado para Serra do Mar. Holos, Ribeirão Preto, 184 pp.

- Fiorillo BF, da Silva BR, Menezes FA, Marques OAV, Martins M (2020) Composition and natural history of snakes from Etá Farm region, Sete Barras, south-eastern Brazil. ZooKeys 931: 115–153. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.931.46882

- Photographic record by Rafael Mana.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Photographic record by Frans Lanting.

- Photographic record by Juan Miguel Artigas.

- Photographic record by Paul Smith.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Rivas G (2002) Erythrolamprus aesculapii. Diet. Herpetological Review 33: 140.

- Greene HW (1976) Scale overlap as a directional sign stimulus for prey ingestion by ophiophagous snakes. Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 41: 113–120. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1976.tb00473.x

- Marques OAV (1996) Biologia reprodutiva da cobra-coral Erythrolamprus aesculapii Linnaeus (Colubridae), no sudeste do Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Zoologia 13: 747–753. DOI: 10.1590/S0101-81751996000300022

- Marques OAV, Puorto G (1994) Dieta e comportamento alimentar de Erythrolamprus aesculapii, uma serpente ofiófaga. Revista Brasileira de Biologia 54: 253–259.

- Lopes Santos D, Vaz-Silva W (2012) Predation of Phimophis guerini and Ameiva ameiva by Erythrolamprus aesculapii (Snake: Colubridae). Herpetology Notes 5: 495–496.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Hudson AA, Sousa BM (2019) Erythrolamprus aesculapii (False Coral Snake). Reproduction, diet and defensive behavior. Herpetological Review 50: 155–156.

- Sazima I, Abe AS (1991) Habits of five Brazilian snakes with coral-snake pattern, including a summary of defensive tactics. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 26: 159–164.

- Marques OAV, Sazima I (2004) História natural dos répteis da Estação Ecológica Juréia-Itatins. In: Marques OAV, Duleba W (Eds) Estação Ecológica Juréia-Itatins Ambiente físico, flora e fauna. Holos, Ribeirão Preto, 257–277.

- Quelch JJ (1893) Venom in harmless snakes. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 17: 30–31.

- Sánchez MN, Teibler GP, Sciani JM, Casafus MG, Marunak SL, Mackessy SP, Peichoto ME (2019) Unveiling toxicological aspects of venom from the Aesculapian False Coral Snake Erythrolamprus aesculapii. Toxicon 164: 71–81. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2019.04.007

- Menegucci RC, Bernarde PS, Monteiro WM, Ferreira Neto P, Martins M (2019) Envenomation by an opisthoglyphous snake, Erythrolamprus aesculapii (Dipsadidae), in southeastern Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 52: e20190055. DOI: 10.1590/0037-8682-0055-2019

- Salomão MG, Albolea ABP, Almeida-Santos SM (2003) Colubrid snakebite: a public health problem in Brazil. Herpetological Review 34: 307–312.

- Photographic record by Philip Stouffer.

- Bustos ML (2019) Contribución al estudio de las parasitosis que afectan a los Colúbridos en cautiverio: posible correlación con las propiedades de sus venenos. MSc thesis, Universidade Federal da Integração Latino-Americana, 105 pp.

- Hladki AI, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N, Nogueira C, Gagliardi G, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Catenazzi A, Gonzales L, Schargel W, Rivas G, Murphy J (2019) Erythrolamprus aesculapii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T203509A2766817.en

- Serrano F, Díaz-Ricaurte JC (2018) Erythrolamprus aesculapii (Linnaeus, 1758). Catálogo de Anfibios y Reptiles de Colombia 4: 48–53.

- Fischer W, Godoi RF, Filho ACP (2018) Roadkill records of reptiles and birds in Cerrado and Pantanal landscapes. Check List 14: 845–876. DOI: 10.15560/14.5.845

- Hurtado-Gómez JP (2016) Systematics of the genus Erythrolamprus Boie 1826 (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) based on morphological and molecular data. PhD thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 62 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Kullander SO, Fang F (2009) Danio aesculapii, a new species of danio from south-western Myanmar (Teleostei: Cyprinidae). Zootaxa 2164: 41–48. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.189031

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Erythrolamprus aesculapii in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Quebrada San Pedro | Serrano & Díaz-Ricaurte 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Tres Esquinas del Caguán | Serrano & Díaz-Ricaurte 2023 |

| Colombia | Meta | Río Guayas | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | RN La Isla Escondida | Photo by Ferdy Christant |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | UIMNH 62871; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tunants | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ahuano | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Colonso Chalupas (near Ikiam) | Photo by Humberto Castillo |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Loreto | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Suno | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Ávila Viejo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bigal River Biological Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca, 130 km S of | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | Photo by Thierry García |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tambococha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alzamada | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bobonaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Río Bobonaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Capahuari | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chichirota | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mouth of Río Romarizo | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Garza-1 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo, 4 km NW of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Reserva Río Anzu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Tigre | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Curcio et al. 2015 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación de la Católica en Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Hidroeléctrica Coca Codo Sinclair | MECN & ENTRIX 2009–2013 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Maycu | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aguaruna Village | MVZ 163323; VertNet |