Published May 12, 2018. Updated April 8, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Klebba’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas klebbai)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Dipsas klebbai

English common name: Klebba’s Snail-eating Snake.

Spanish common name: Caracolera de Klebba.

Recognition: ♂♂ 107.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=74.9 cm. ♀♀ 87.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=63.0 cm..1 Dipsas klebbai is the only snake in its area of distribution having a light brown dorsum with 27–36 dark brown to black cream-edged oblong blotches and no white transverse line on the snout (Fig. 1).1 The head is black with different degrees of whitish edging on the labial scales. This species differs from D. catesbyi by having a loreal scale in contact with the orbit as well as by lacking a white transverse line on the snout.2,3

Figure 1: Individuals of Dipsas klebbai from Ecuador: La Bonita, Sucumbíos province (); Yanayacu Biological Station, Napo province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Dipsas klebbai is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen montane forests and cloud forests.1 The species also occurs in forest edges, pastures, rural gardens, and houses.1,4 Klebba’s Snail-eating Snakes are active at night, especially between 6:00 pm and 2:00 am, but may at times bask on leaf-litter during the day.1,4 Their activity occurs both at ground level as well as on low (0.5–5 m above the ground) understory vegetation.1 During the day, individuals have been found resting, coiled underground in pastures, among shrubs in rural gardens, or perched on leaves 300 cm above the ground.1 At dusk, particularly after a warm day, they have been seen crossing roads.1 In captivity, several individuals from Napo province consumed only slugs.4 The mollusks are presumably immobilized by the use of toxins secreted by the mucous cells of the infralabial glands.5 Nevertheless, all snakes in the genus Dipsas are considered harmless to humans. They never attempt to bite, resorting instead to coiling into a defensive ball posture and producing a musky and distasteful odor when threatened.1,6 Clutches of 5–9 eggs of D. klebbai have been found under rotten logs.1,4

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..1 Since it has only been recently described,1 Dipsas klebbai has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Here, it is provisionally assigned to the LC category because the species has a wide distribution spanning many protected areas. All known localities of occurrence of D. klebbai are within the buffer zone of the following protected areas: Parque Nacional Cayambe Coca, Parque Nacional Sumaco Napo Galeras, Reserva Ecológica Antisana, and Reserva Ecológica Cofán Bermejo.1 Furthermore, these snakes are abundant in degraded environments, suggesting a degree of tolerance for habitat modification.1

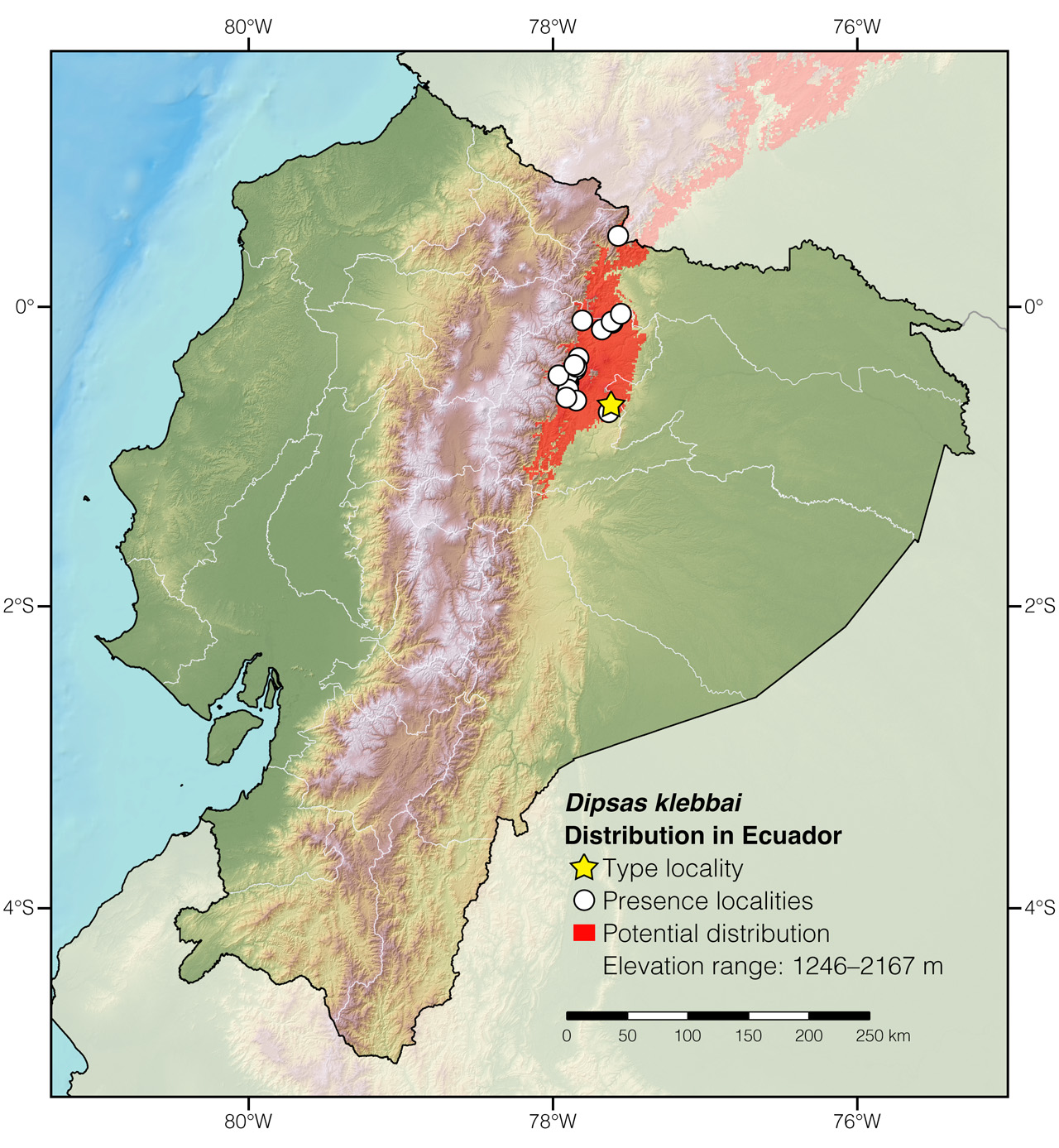

Distribution: Dipsas klebbai is native to the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in northeastern Ecuador (Fig. 2). A series of records from Huila and Caquetá in Colombia are tentatively assigned to this species.

Figure 2: Distribution of Dipsas klebbai in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Pacto Sumaco, Napo province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Dipsas comes from the Greek dipsa (=thirst)7 and probably refers to the fact that the bite of these snakes was believed to cause intense thirst. The specific epithet klebbai honors Casey Klebba, in recognition of his appreciation of Andean wildlife and his invaluable support of field expeditions to remote areas of Ecuador.1

See it in the wild: Klebba’s Snail-eating Snakes can be seen at a rate of about once every few nights, especially after a warm day in forested areas around the towns Baeza and El Chaco in Ecuador. The snakes are more easily detected by scanning arboreal vegetation along roads and trails.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Diego Piñán for providing information on the natural history of Dipsas klebbai.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Klebba’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas klebbai). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/EPHM5462

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Salazar-Valenzuela D, Mebert K, Peñafiel N, Aguiar G, Sánchez-Nivicela JC, Pyron RA, Colston TJ, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Venegas PJ, Guayasamin JM, Torres-Carvajal O (2018) Systematics of South American snail-eating snakes (Serpentes, Dipsadini), with the description of five new species from Ecuador and Peru. ZooKeys 766: 79–147. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.766.24523

- Peters JA (1956) An analysis of variation in a South American snake, Catesby’s Snail-Sucker (Dipsas catesbyi Sentzen). American Museum Novitates: 1–41.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Field notes of Diego Piñán and Fernando Vaca.

- De Oliveira L, Jared C, da Costa Prudente AL, Zaher H, Antoniazzi MM (2008) Oral glands in dipsadine “goo-eater” snakes: morphology and histochemistry of the infralabial glands in Atractus reticulatus, Dipsas indica, and Sibynomorphus mikanii. Toxicon 51: 898–913. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.12.021

- Cadle JE, Myers CW (2003) Systematics of snakes referred to Dipsas variegata in Panama and Western South America, with revalidation of two species and notes on defensive behaviors in the Dipsadini (Colubridae). American Museum Novitates 3409: 1–47.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dipsas klebbai in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda La Unión | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Huila | Las Orquídeas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Huila | Vereda Salen | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Baeza | Photo by Fernando Vaca |

| Ecuador | Napo | Baeza, 4 km S of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Bermejo | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Napo | Bermejo, 1 km S of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Borja | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Borja, 2 km E of | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cascada de San Rafael | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Coca Codo Sinclair | MECN & ENTRIX 2009–2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | El Chaco | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hacienda Cumandá | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Las Palmas | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco* | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Azuela | Harvey 2008 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Cascabel | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Quijos | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Rafael | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Santa Rosa | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sardinas | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Virgen de Guacamayos, 1.8 km E of | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yanayacu Biological Station | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Bonita | Arteaga et al. 2018 |