Published March 11, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Long-tailed Whipsnake (Chironius multiventris)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Chironius multiventris

English common names: Long-tailed Whipsnake, Long-tailed Sipo, South American Sipo.

Spanish common name: Serpiente látigo colilarga.

Recognition: ♂♂ 261.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=168.1 cm. ♀♀ 209.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=132.9 cm..1 Chironius multiventris can be identified by having 12 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body, a divided anal plate, and 161–196 ventral scales.1 This species exhibits an ontogenetic shift in coloration, with juveniles presenting a light olive-brown dorsum with lighter colored scales (sometimes forming bars), and adults having a dark-brown dorsum with black paravertebral keels forming two longitudinal lines (Fig. 1).1–3 Both juveniles and adults have a bright yellow belly.1–3 Chironius multiventris differs from C. exoletus by having more ventral scales (123–162 in C. exoletus) and a proportionally longer tail.1,2 From C. fuscus and C. leucometapus, it differs by having 12 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body and a divided anal plate.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Chironius multiventris from Ecuador: Yasuní National Park, Orellana province (); Suchipakari Lodge, Napo province (); Napo Wildlife Center, Sucumbíos province ().

Natural history: Chironius multiventris is a fairly common diurnal and semi-arboreal snake that inhabits primary rainforests, gallery forests, and occasionally disturbed areas such as roadsides and rural gardens.1–3 During the day, Long-tailed Whipsnakes can be seen actively moving on the forest floor or on shrubs and trees up to 7 m above the ground.4 At night, they sleep coiled on vegetation up to 9 m above the ground.1,3,4 Their diet is composed mainly of frogs, but reptiles (including Anolis fuscoauratus and Polychrus marmoratus) are also consumed.1–5 Gravid females have been found to contain 7–10 oviductal eggs,1,3 but the real clutch size is not known. The Long-tailed Whipsnake, when disturbed, can exhibit an aggressive behavior which consists of raising the first third of the body while striking repeatedly.4 However, this is an aglyphous snake, meaning it lacks venom-inoculating teeth.1 In Ecuador, two males of C. multiventris were observed entangled in combat.6

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..7 Chironius multiventris is listed in this category primarily because the species is widely distributed, occurs in protected areas, and is able to tolerate some degree of habitat disturbance so long as forest remains.7 Although little is known about threats to this species, deforestation and the decline in the number of anuran prey due to pollution and emerging diseases could have a negative localized impact on some populations. Chironius multiventris can also be particularly affected by vehicular traffic, being frequently found dead-on-road throughout its range.4

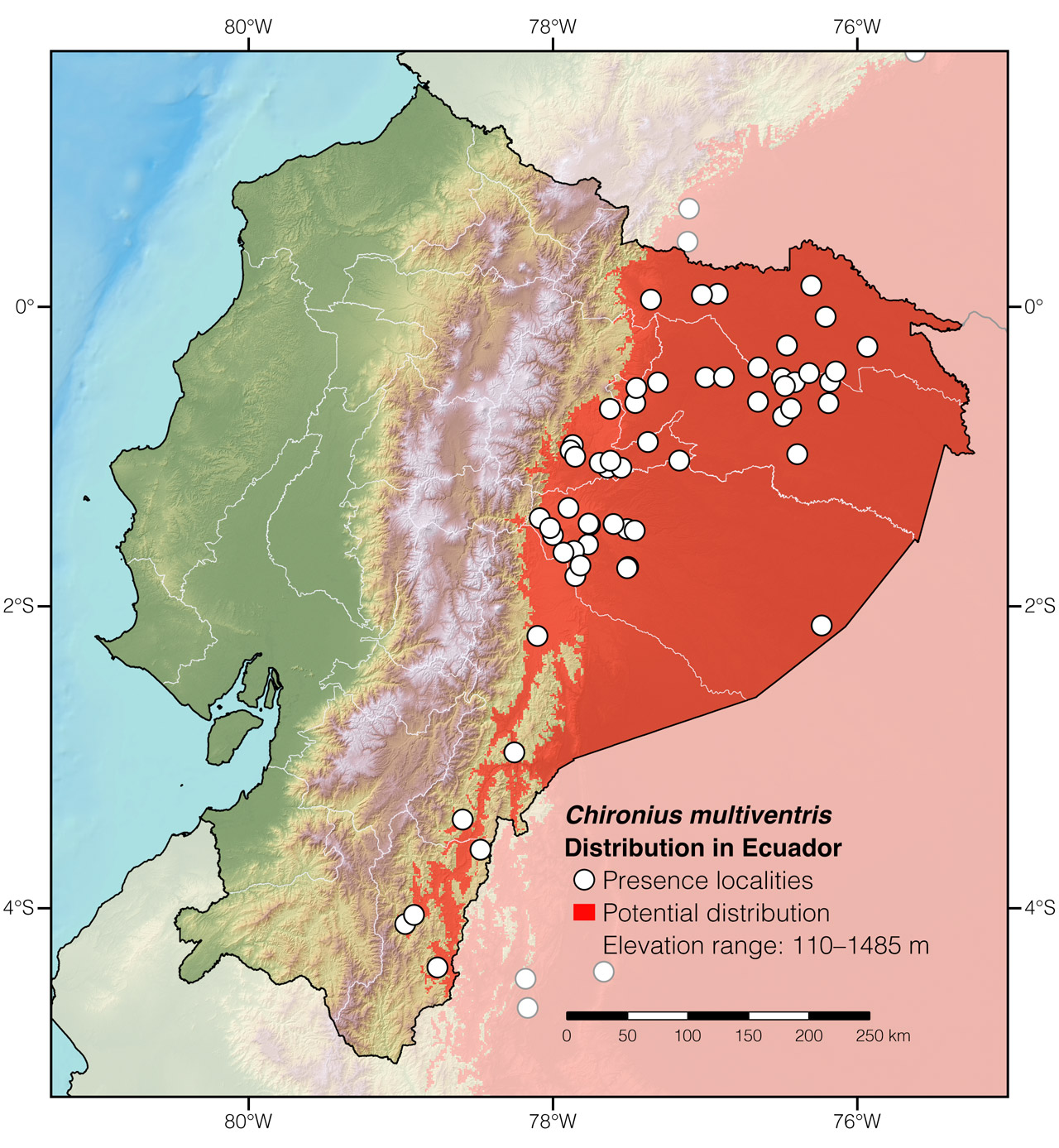

Distribution: Chironius multiventris is widespread throughout the Amazon rainforest Brazil, Peru, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Colombia, Suriname, Guyana, French Guyana and Venezuela.

Figure 2: Distribution of Chironius multiventris in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chironius was coined by Leopold Fitzinger in 1826, but likely originated in 1790 with Blasius Merrem, who used the common name “Chiron’s Natter” for Linnaeus’ Coluber carinatus.8 In Greek mythology, Chiron was a centaur reputed for his healing abilities. Likewise, in ancient Greek civilization, sick people hoping for a cure flocked to temples where sacred snakes were carefully tended and presented to the sufferers. The specific epithet multiventris comes from the words multus (=many) and ventris (=venter), and refers to the high number of ventral scales.1

See it in the wild: Long-tailed Whipsnakes are particularly common at Yasuní National Park, where they are recorded at a rate of about twice a week especially along clearings during sunny days.

Special thanks to Mami Okura for symbolically adopting the Long-tailed Whipsnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Esteban Garzón-FrancoaAffiliation: Colecciones Biológicas de la Universidad CES (CBUCES), Facultad de Ciencias y Biotecnología, Universidad CES, Medellín, Colombia. and Laura Gómez-Mesa,bAffiliation: Escuela de Ciencias Aplicadas e Ingeniería, Universidad EAFIT, Medellín, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Garzón-Franco E, Gómez-Mesa L, Arteaga A (2024) Long-tailed Whipsnake (Chironius multiventris). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZZGF1100

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Wiest Jr JA, Cei JM (1993) Revision of the Neotropical snake genus Chironius Fitzinger (Serpentes, Colubridae). Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino, Torino, 280 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Roberto IJ, Ramos Souza A (2020) Review of prey items recorded for snakes of the genus Chironius (Squamata, Colubridae), including the first record of Osteocephalus as prey. Herpetology Notes 13: 1–5.

- Photo by Kestrel DeMarco.

- Ortega A, Hoogmoed M, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Catenazzi A, Nogueira C, Schargel W, Rivas G (2016) Chironius multiventris. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T44580143A44580148.en

- Merrem B (1790) Beitrage zur Naturgeschichte. Duisburg um Lemgo, Berlin, 141 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chironius multiventris in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Reserva La Isla Escondida | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda Islas de Cartagena | Borja-Acosta & Galeano 2024 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Namangoza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Turula | AMNH 23285; examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hakuna Matata Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ikiam University | Photo by Grace Reyes |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Neumane | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Runa Huasi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sacha Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Suchipakari Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Ávila Viejo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Camino a Bogi 2 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | EPF, 3 km NW of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Mandaripanga Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Coca | MCZ 164700; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní, 200 km upstream from mouth | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arutam | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento K4 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Centro Ecológico Zanja Arajuno | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Finca Heimatlos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Fundación Hola Vida | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Jardín Botánico Las Orquídeas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mouth of Río Villano | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Paparawua | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Sarayakillo | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | San Pascual | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | AMNH 36038; examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay In Situ | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Universidad Estatal Amazónica | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Upper Río Curaray | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha | MHNG 2399.037; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Playas del Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | MHNG 2458.1; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sansahuari | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tucán Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Copalinga | Reeves et al. (unpublished) |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Reserva Maycu | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Subcuenca del Río Tundayme | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Timbara | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Perú | Amazonas | Boca del Río Cenepa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Boca del Río Santiago | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami | MVZ 163256; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Centro Unión | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Cordillera Escalera | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | Nogueira et al. 2019 |