Published October 10, 2019. Updated July 20, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis vicina)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis vicina

English common names: Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise, Iguana Cove Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Cerro Azul, tortuga gigante de Cerro Azul.

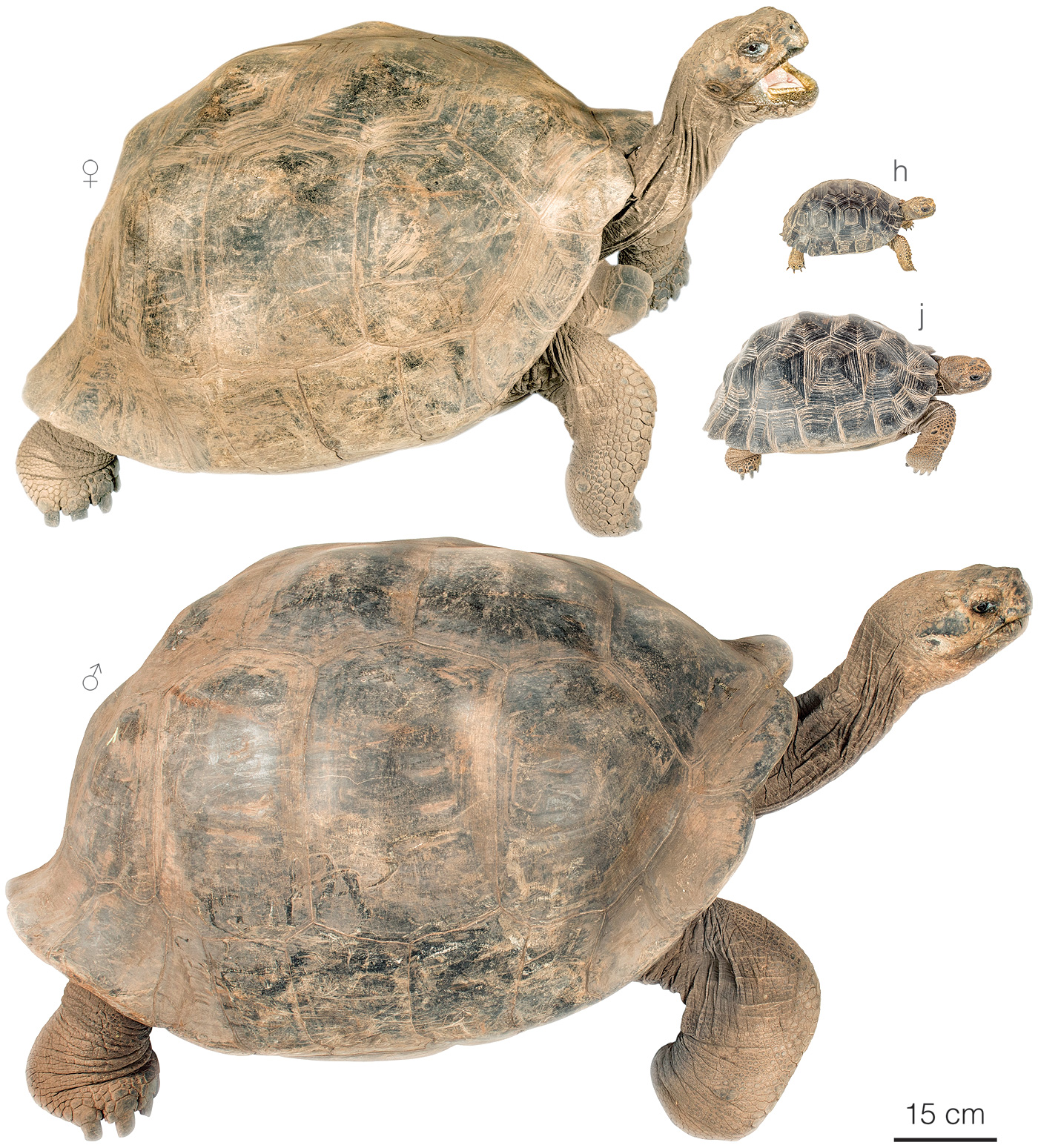

Recognition: ♂♂ 117.1 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 93 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace..1 Chelonoidis vicina is a giant tortoise with a domed carapace (Fig. 1). It is generally the only species of tortoise occurring on Cerro Azul Volcano. However, there are some places where it can be found living alongside C. guntheri, a species in which some adult individuals have a distinctive dorsally flattened carapace.1 With the exception of these flattened individuals, tortoises of the two species may be indistinguishable without the use of genetic information.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Chelonoidis vicina from Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza, Isabela Island, Galápagos.

Natural history: Chelonoidis vicina is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits the seasonally dry forests, evergreen forests, and dry grasslands of Cerro Azul Volcano.1 These tortoises spend most of the daytime feeding or moving.2 During the hot afternoon hours, they rest in the shade or wallow in mud or in damp soil.2 Their diet includes grasses, leaves of trees, cacti, lichens, and berries, including those from the strongly irritant manzanillo.2–6 The males of C. vicina fight with each other using a combination of biting, gaping, neck extensions, and shell-bumping.7 The juveniles stay in warmer lowland areas for their first 10–15 years of life.8 As adults, they migrate from inland to coastal areas along well-established trails to forage on lush new vegetation after the rains.2 There are records of introduced pigs and fire ants preying upon the eggs and hatchlings of this tortoise species.8,9

Conservation: Endangered Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the near future..10 It is estimated that 97–98% of the population of Chelonoidis vicina disappeared in the last 180 years.10,11 The number of Cerro Azul Giant Tortoises declined catastrophically from about 18,000 individuals before human impact down to an estimated 400–600 in the 1970s.10,11 Causes of the population decline, some of which are ongoing, include extensive overexploitation for food by sailors (mostly whalers) and settlers2,8 and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, dogs, rodents, and fire ants), which either prey on tortoise eggs and hatchlings or destroy their habitat.8,9,12 To this day, the recovery of C. vicina remains restrained.10 Pigs and ants continue to decimate nests, feral cattle trample nests and compete with the tortoises for resources, introduced vegetation degrades natural habitats and interferes with migratory routes, and illegal slaughter and poaching of tortoises still occurs.10 Another threat faced by C. vicina is volcanic eruptions, which cause direct mortality and destroy and fragment tortoise habitat.10 Today, only four populations of the Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise remain in the wild.13 These account for a total of about 1,800–2,700 animals,10 but the actual number of purebred individuals may be much lower.13 Whether these numbers are increasing is unknown. Some of the positive conservation actions carried out by the Galápagos National Park include the eradication of goats and the establishment of a head-starting program at the Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza, in which young tortoises are raised in captivity and subsequently released into the wild.10

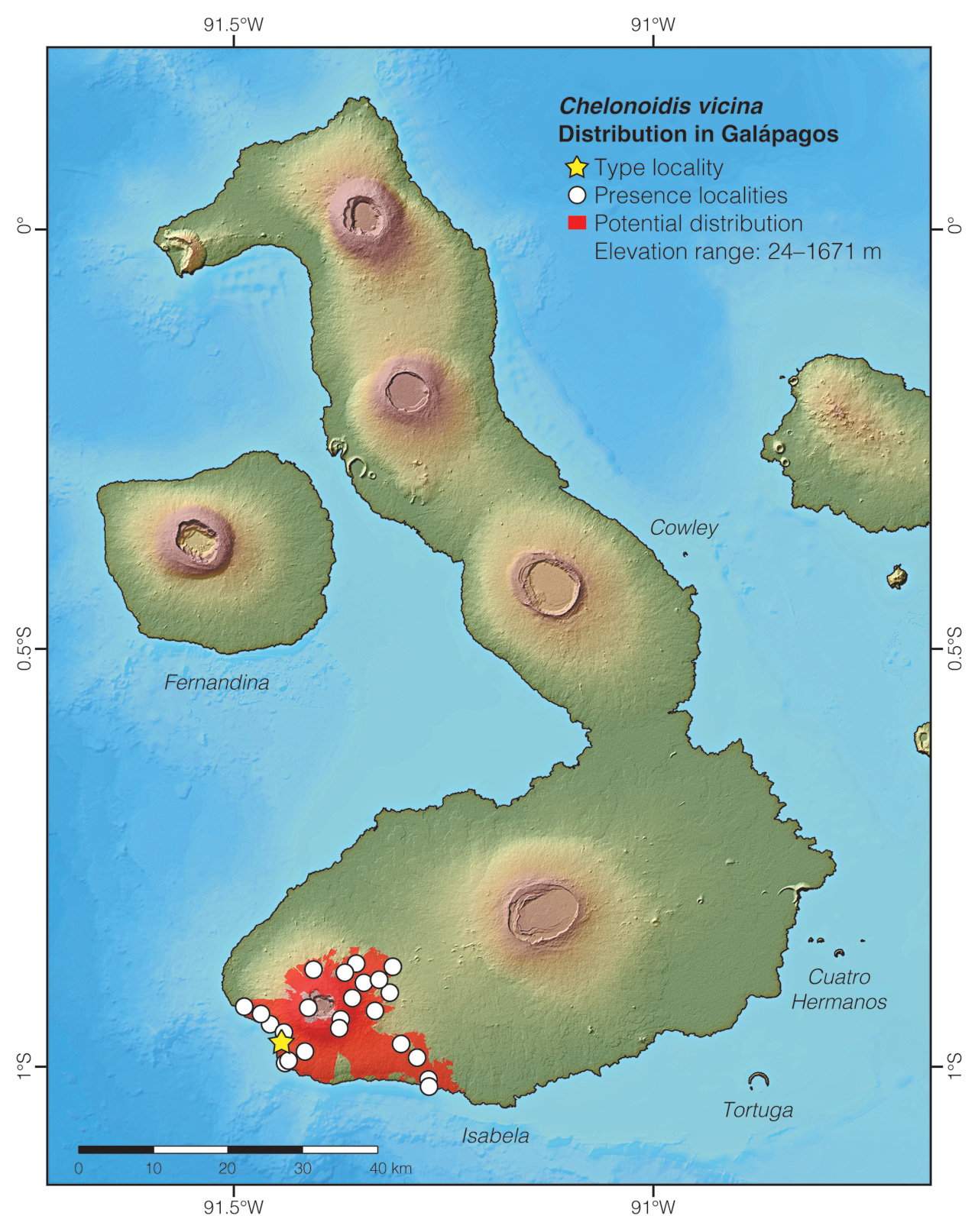

Distribution: Chelonoidis vicina is endemic to an area of approximately 254 km2 on Cerro Azul Volcano in southwestern Isabela Island, Galápagos, Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Chelonoidis vicina in Galápagos. The star corresponds to the type locality: Iguana Cove. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (=tortoise).14 The specific epithet vicina comes from the Latin word vicinus (=neighboring) and probably refers to the distribution of this species, which is adjacent to the distribution of C. guntheri.15

See it in the wild: The few remaining populations of purebred Chelonoidis vicina occur on and around Cerro Azul Volcano and the access to these sites is restricted by the Galápagos National Park. Researchers and park rangers may visit the habitat of C. vicina, but only in the context of a scientific expedition or a conservation action. Head-started juveniles of C. vicina can be seen at the Centro de Crianza Arnaldo Tupiza.

Special thanks to Kerri Murphy for symbolically adopting the Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa CacconecAffiliation: Yale University, New Haven, United States.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2024) Cerro Azul Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis vicina). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/BRSG5226

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Heller E (1903) Papers from the Hopkins-Stanford Galápagos Expedition, 1898-1899. XIV. Reptiles. Proceedings of the Washington Academy of Sciences 5:39–98.

- Darwin CR (1845) Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the command of Capt. Fitz-Roy, R.N. John Murray, London, 519 pp.

- Daggett FS (1915) A Galápagos tortoise. Science 42: 933–934. DOI: 10.1126/science.42.1096.933.b

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin’s journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- Schafer SF, Krekorian CO (1983) Agonistic behavior of the Galápagos tortoise, Geochelone elephantopus, with emphasis on its relationship to saddle-backed shell shape. Herpetologica 39: 448–456.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld D, Snell H, Fritts T, MacFarland C, Tapia W, Naranjo S (2004) Estado actual de las poblaciones de tortugas terrestres gigantes (Geochelone spp., Chelonia: Testudinidae) en las islas Galápagos. Ecología Aplicada 3: 98–111.

- Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Caccone A (2018) Chelonoidis vicina. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T9028A144765855.en

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part I: Status of the surviving populations. Biological Conservation 6: 118–133.

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Edwards DL, Garrick RC, Tapia W, Caccone A (2014) Cryptic structure and niche divergence within threatened Galápagos giant tortoises from southern Isabela Island. Conservation Genetics 15: 1357–1369. DOI: 10.1007/s10592-014-0622-z

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Van Denburgh J (1914) The gigantic land tortoises of the Galápagos Archipelago. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 4: 203–374.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chelonoidis vicina in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cerro Azul, NE slope | Fritts 2008 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cerro Azul, SE rim | Fritts 2008 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cinco Cerros | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Cinco Cerros, 3 km NW of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Eastern lowlands of Cerro Azul | Swingland 1989 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Gavilanes | Ciofi et al 2006 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Iguana Cove, 2 km SE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Iguana Cove, 4 km NW of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Iguana Cove, 6 km SE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Iguana Cove* | Günther 1874; Garman 1917 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Las Tablas | Márquez et al 1995 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Cráteres | Márquez et al 1995 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Pegas | Benavides et al 2011 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Pegas, 3 km SE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Pegas, 5 km E of | Ciofi et al 2006 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Pegas, 6.5 km NE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Pegas, 6.5 km SE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Los Túneles, 3 km W of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Nesting zone | Pritchard 1996 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Essex | Pritchard 1996 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Essex, 1 km NE of | Edwards et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Southern slopes of Cerro Azul | Heller 1903 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Summit of Cerro Azul | Swingland 1989 |