Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis porteri

English common names: Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise, Western Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise, Indefatigable Island Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Santa Cruz, tortuga gigante del oeste de Santa Cruz.

Recognition: ♂♂ 115 cm ♀♀ 96.5 cm. Chelonoidis porteri is a giant tortoise having a strongly domed carapace. It is the only species of giant tortoise known to naturally occur in the west of Santa Cruz Island.

Picture: Adult male. Zoológico de Quito. Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Zoológico de Quito. Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Santa Cruz Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Santa Cruz Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Zoológico El Arca. Napo, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Extremely common. Chelonoidis porteri is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise that inhabits evergreen forests, deciduous forests, farmlands, and areas of introduced vegetation. Individuals of C. porteri are most active from 8:00 to 17:30. They rest in water holes,1 sleep in areas of tall grass,1 or actively move in search of food. Their diet largely consists of native and introduced vegetation, such as grasses, herbs, forbs, sedges, leaves of trees, shrubs, cacti, vines, moss, lichen, flowers, and fruits (including those from the strongly irritant manzanillo), but also includes carrion.2–5 With increasing frequency, Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoises are including a greater proportion of fruits from invasive plants (passion fruit, blackberry, and guava) in their diet.6

At night, Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoises sleep in areas partly secluded by vegetation or rocks.1 They can spend up to two days resting while regulating their body temperature in a water hole,3 especially during the dry season. Adults usually move 21–730 m daily.3 The majority (77.3%) of adult tortoises are migratory,7 traveling up to 10 km from inland to coastal areas to exploit new vegetation after the rains.7,8 Some (18.2%) are nomadic, moving apparent to a random walk, instead of from one area to another and back.7 Male Chelonoidis porteri fight each other using a combination of biting, rearing up, hissing with open mouths, and shell-bumping.1,3 Females also fight with each other during the nesting season. They appear to compete and fight over suitable nesting areas by rearing up and hissing with open mouths.9

Courtship in the Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise takes place from February to March.1 When mating, the tortoises produce resounding guttural sounds. In May, females descend into the drier lowlands at 6–149 m in elevation to dig 20–33 cm deep1,9,10 nests. Females lay 3–21 (but usually 7–21) eggs11,12 that take 110–250 days to hatch.13 The hatchlings disperse up to 600 m away during their first two years of life and become sedentary in <400 m2 areas.9 They feed on fallen cactus pads and dry grass.14 The hatchlings are preyed upon by owls15 and they were heavily preyed upon by hawks in the past,9 but farmers have now displaced the hawks from Santa Cruz Island. Both the eggs and the neonates are preyed upon by feral pigs, rats, and fire ants.14,16 Individuals of Chelonoidis porteri may live up to 175 years old.17

Conservation: Critically Endangered.18 Chelonoidis porteri is listed in this category because nearly 90% of the population disappeared in the last 180 years.18 The pre-human population size of C. porteri was estimated18 to be ~35,000. Today, about 3,400 individuals remain.18 Causes of the population decline include extensive overexploitation for food by sailors and settlers,19,20 and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, dogs, rodents, and fire ants), which either prey on tortoise eggs and hatchlings or destroy their habitat.14,18 Ongoing threats include predation by feral pigs and rats, egg mortality caused by ants, agricultural land use, disturbance of migratory routes (by fences and blackberry thickets), and occasional human-related mortality.16,18

Today, thanks to conservation efforts by the Galápagos National Park, the Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise population is increasing.18 Some of the most positive actions include ongoing programs to eradicate feral pigs, donkeys, and goats, as well as teaching farmers to use raised barbed wire that may let the tortoises migrate freely instead of closed fencing.18

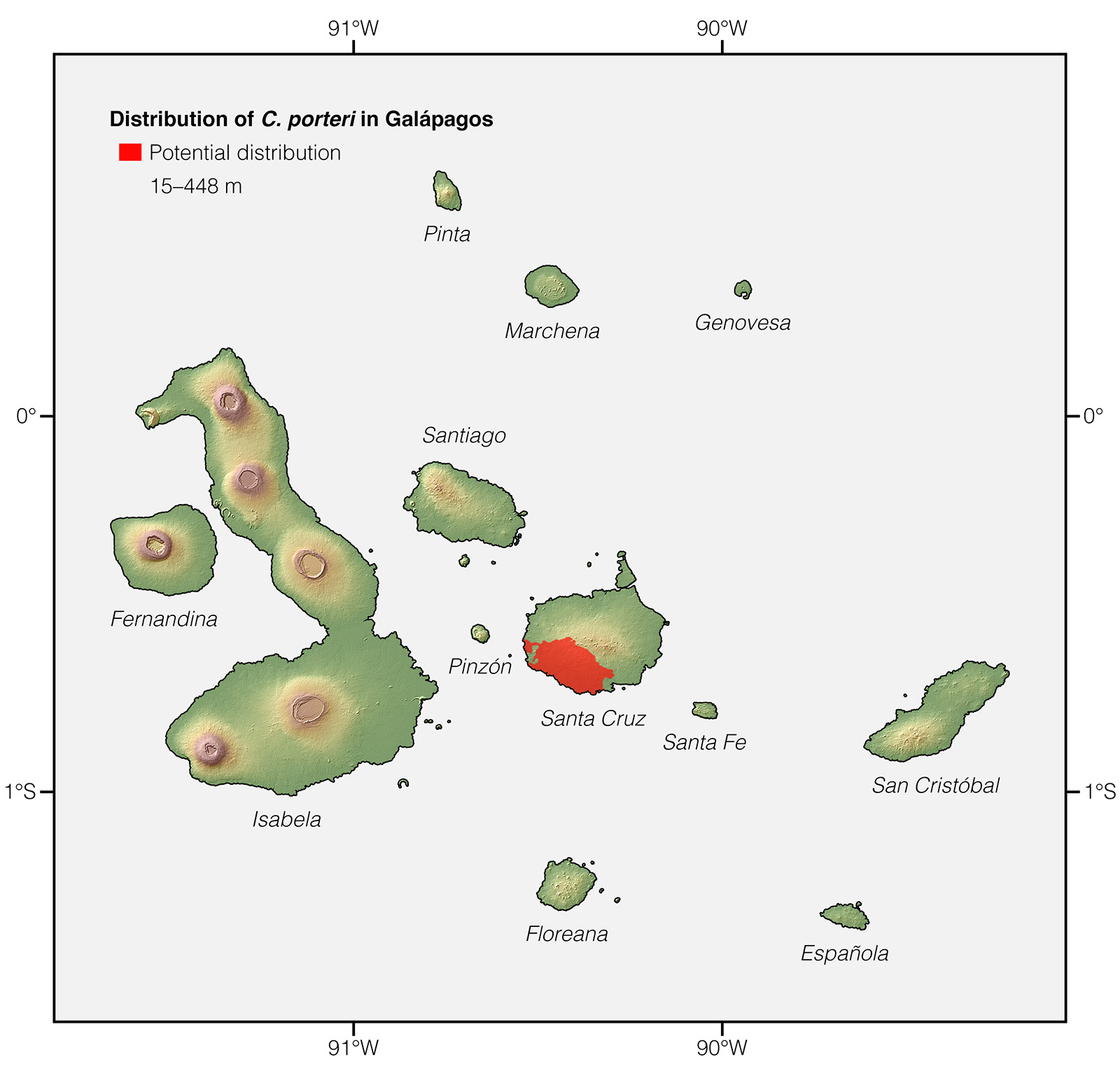

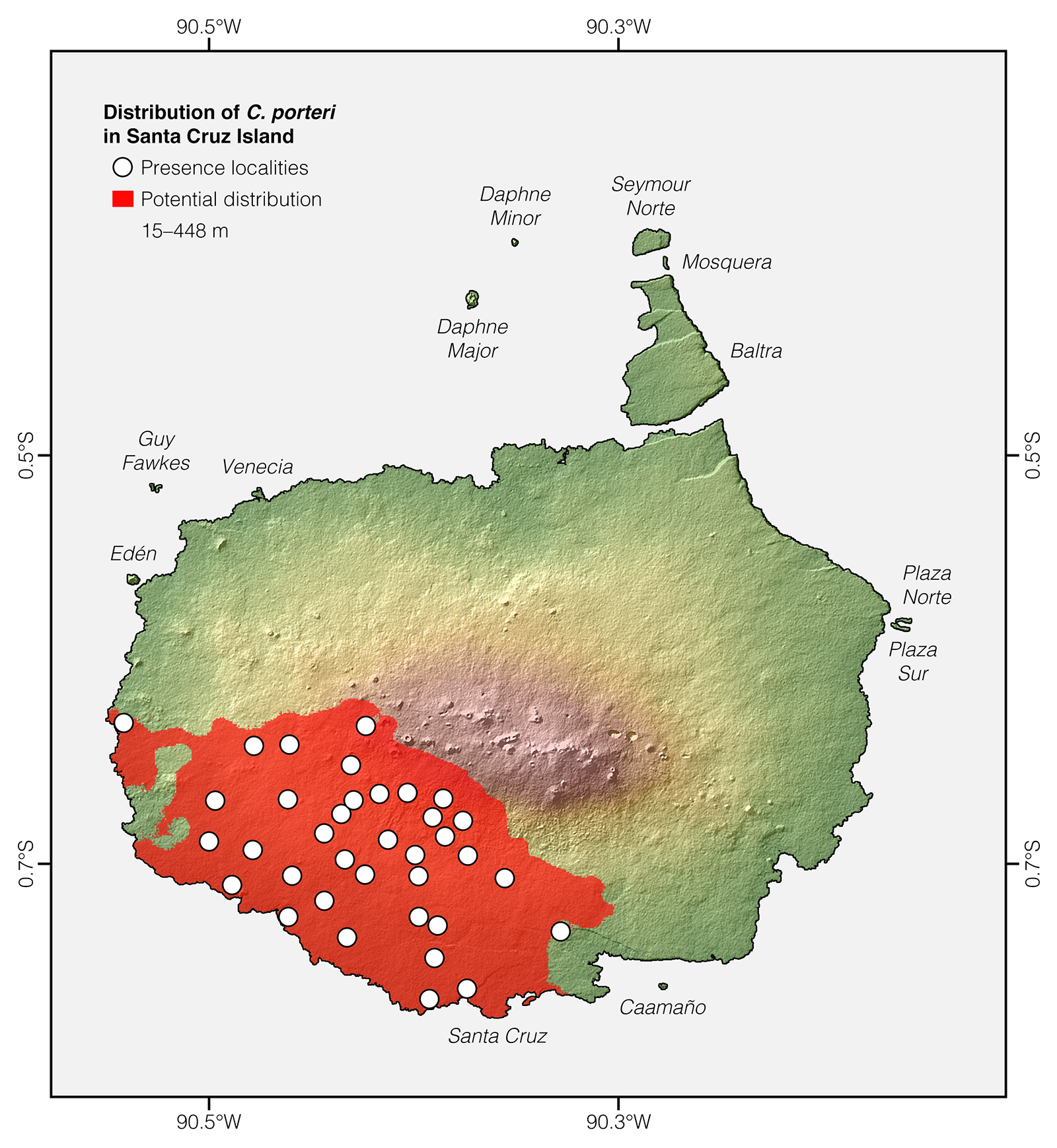

Distribution: Chelonoidis porteri is endemic to an estimated 254 km2 area in the west of Santa Cruz Island. Galápagos, Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).21 The specific epithet porteri honors Captain David Porter of the U.S. Navy, who made important observations about the Galápagos giant tortoises during his cruise in 1813.22

See it in the wild: Individuals of Chelonoidis porteri can be seen year-round with ~100% certainty at Reserva El Chato, Rancho El Manzanillo, and Rancho Primicias, in the highlands of Santa Cruz Island.

Special thanks to Roy Averill-Murray and Chris Alberts for symbolically adopting the Santa Cruz Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone and Diego Ellis.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis porteri. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Carpenter CC (1966) Notes on the behavior and ecology of the Galápagos tortoise on Santa Cruz Island. Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science 46: 28–32.

- Darwin CR (1845) Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the command of Capt. Fitz-Roy, R.N. John Murray, London, 519 pp.

- Rodhouse P, Barling RWA, Clark WIC, Kinmonth AL, Mark AM, Roberts D, Armitage LE, Austin PR, Baldwin SP, Bellairs AD, Nightingale PJ (1975) The feeding and ranging behaviour of Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). The Cambridge and London University Galápagos Expeditions, 1972 and 1973. Journal of Zoology 176: 297–310.

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Cayot LJ (1987) Ecology of giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) in the Galápagos Islands. PhD thesis, New York, United States, Syracuse University.

- Ellis-Soto D, Blake S, Soultan A, Guézou A, Cabrera F, Lötters S (2017) Plant species dispersed by Galapagos tortoises surf the wave of habitat suitability under anthropogenic climate change. PLoS ONE 12: e0181333.

- Bastille-Rousseau G, Gibbs JP, Yackulic CB, Frair JL, Cabrera F, Rousseau LP, Wikelski M, Kümmeth F, Blake S (2017) Animal movement in the absence of predation: environmental drivers of movement strategies in a partial migration system. Oikos 126: 1004–1019.

- Blake S, Yackulic CB, Cabrera F, Tapia W, Gibbs JP, Kümmeth F, Wikelski M (2013) Vegetation dynamics drive segregation by body size in Galápagos tortoises migrating across altitudinal gradients. Journal of Animal Ecology 82: 310–321.

- Diego Ellis, unpublished data.

- Fritts TH, Fritts PR (1982) Race with extinction: herpetological notes of J. R. Slevin's journey to the Galápagos 1905–1906. Herpetological Monographs 1: 1–98.

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part II: Conservation methods. Biological Conservation 6: 198–212.

- Washington Tapia, unpublished data.

- MacFarland CG, Reeder WG (1975) Breeding, raising and restocking of giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus) in the Galápagos Islands. In: Martin RD (Ed) Breding endangered species in captivity. Academic Press, New York, 13–36.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Steadman DW (1982) Fossil birds, reptiles, and mammals from isla Floreana, Galápagos Archipelago. PhD Thesis, Tucson, United States, The University of Arizona.

- Márquez C, Wiedenfeld D, Snell H, Fritts T, MacFarland C, Tapia W, Naranjo S (2004) Estado actual de las poblaciones de tortugas terrestres gigantes (Geochelone spp., Chelonia: Testudinidae) en las islas Galápagos. Ecología Aplicada 3: 98–111.

- Thomson S, Irwin S, Irwin T (1998) Harriet, the Galápagos tortoise. Disclosing one and a half centuries of history. Reptilia 2: 48–51.

- Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Caccone A (2017) Chelonoidis porteri. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- Pritchard PCH (1996) The Galápagos tortoises. Nomenclatural and survival status. Chelonian Research Monographs 1: 1–85.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Günther A (1875) Description of the living and extinct races of gigantic land-tortoises. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 165: 251–284.