Santiago Giant-Tortoise |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Testudinidae | Chelonoidis darwini

English common names: Santiago Giant-Tortoise, James Island Giant-Tortoise, Darwin's Giant-Tortoise.

Spanish common names: Galápago de Santiago, galápago de Darwin, tortuga gigante de Santiago.

Recognition: ♂♂ 125.6 cm ♀♀ 82.1 cm. Chelonoidis darwini is a giant tortoise having a carapace shape intermediate between saddlebacked and domed. It is the only species of giant tortoise known to naturally occur on Santiago Island.

Picture: Adult female. Santiago Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile. Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Common. Chelonoidis darwini is a diurnal and terrestrial tortoise inhabiting deciduous forests, evergreen montane forests, and humid grasslands.1 Individuals of C. darwini feed on cacti, herbs, and grasses,1,2 and obtain water from their diet and from temporary pools.1 Santiago Giant-Tortoises can survive without water for six months,2 and perhaps longer. Juveniles of C. darwini stay in warmer lowland areas of the island during their first 10–15 years.3 As adults, they move across their elevation range. Females lay 4–14 eggs.1,4 Hatchlings are preyed upon by hawks.1 In captivity, Santiago Giant-Tortoises reach sexual maturity at about 20 years of age.5 When mating, the tortoises produce resounding guttural sounds.

"The terrapin can, and does, live six or more months without water, as he is provided with a vessel or bladder, in which he lays in a stock which he carries with him. This water is at any time as clear as amber and seems entirely pure and clean."

Weston Howland, whaler, 1830.2

Conservation: Critically Endangered.5 Chelonoidis darwini is listed in this category because nearly 95% of the population disappeared in the last 180 years.5 The number of Santiago Giant-Tortoises declined catastrophically from about 24,000 individuals before the discovery of the Galápagos Islands to 500–700 in the early 1970s.5,6 The bulk of the decline occurred between 1788 and 1868 during the whaling decades in the Pacific.2,7 Causes of the population decline include extensive overexploitation for food by sailors (mostly whalers) and settlers,2,6 and the introduction of exotic species (including goats, pigs, donkeys, and rodents), which either prey on the eggs and the hatchlings of C. darwini, or destroy tortoise habitat.3,5

"The officers and men having returned from their mountain expedition, each with a large terrapin secured on his back that would weigh seventy-five pounds or more, lunch and a good drink of water was served. They then returned to the feeding ground for another load, which they came back with in time to load the boat and return to the ship before dark, with a supply of delicious food for a month or more."

Weston Howland, whaler, 1830.2

Today, there are about 1,700 Santiago Giant-Tortoises,5 and these numbers are growing thanks to the head-starting program of the Galápagos National Park, in which young tortoises are raised in captivity and subsequently released into the wild, where goats, pigs, and donkeys have been successfully eradicated.5

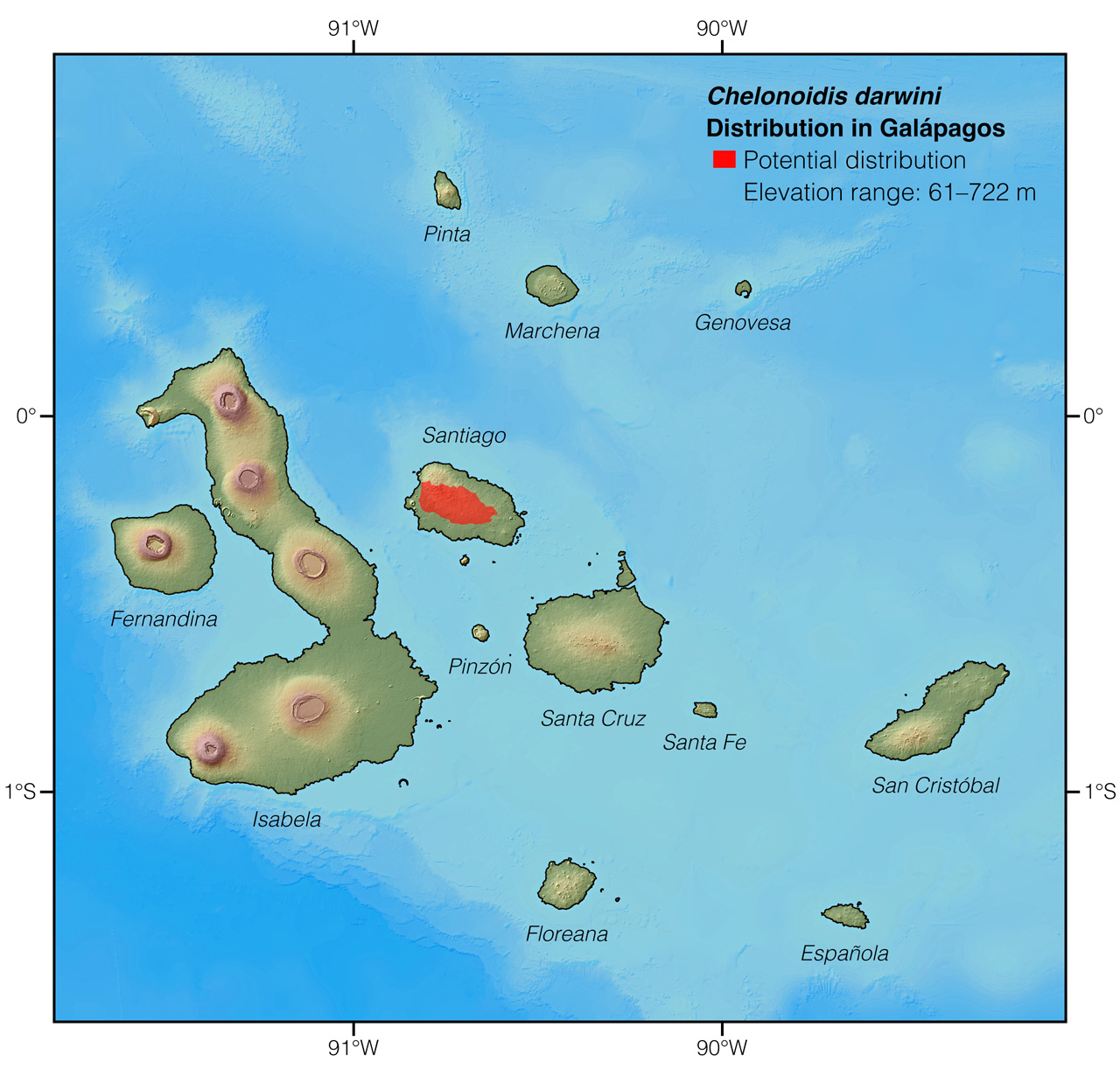

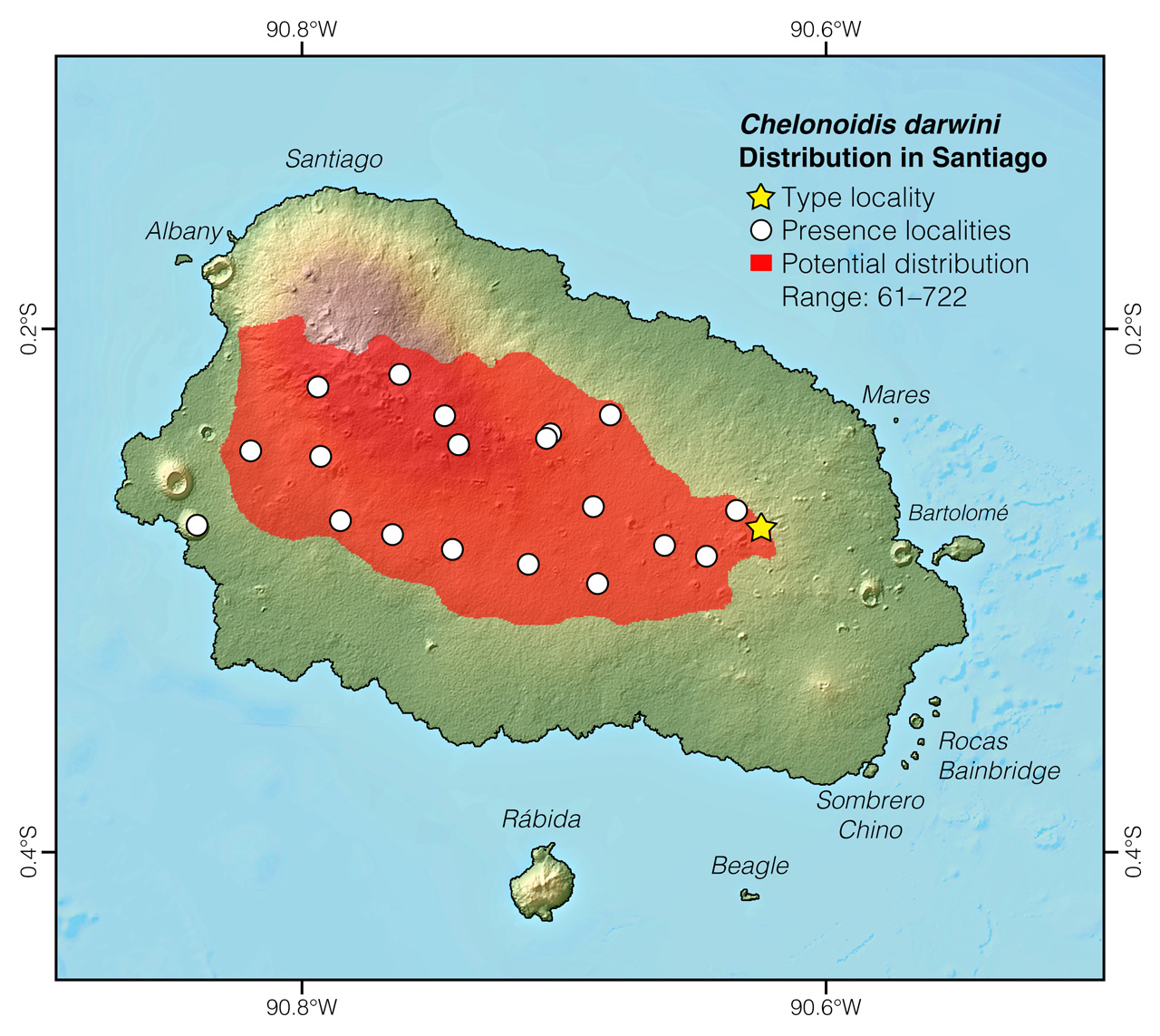

Distribution: Chelonoidis chathamensis is endemic to an estimated 196 km2 area on the highlands of Santiago Island. Galápagos, Ecuador.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonoidis comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “tortoise”).8 The specific epithet darwini honors Charles Darwin.9 Darwin spent nine days (8–17 October, 1835) on Santiago Island. During his stay, he observed the tortoises in the highlands and regularly fed on tortoise meat, which he describes as "delicious in soup".10

See it in the wild: The few remaining populations of purebred Chelonoidis darwini occur on the highlands of Santiago Island, which are inaccessible to tourism. Researchers and members of the Galápagos National Park may visit the habitat of C. darwini, but only in the context of a scientific expedition or a conservation agenda. Head-started juveniles of C. darwini can be seen at the Centro de Crianza Fausto Llerena on Santa Cruz Island.

Special thanks to Jeanne O’Connell for symbolically adopting the Santiago Giant-Tortoise and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Adalgisa Caccone.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2020) Chelonoidis darwini. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Townsend CH (1925) The Galápagos tortoises in their relation to the whaling industry: a study of old logbooks. Zoologica 4: 55–135.

- Swingland IR (1989) Geochelone elephantopus. Galápagos giant tortoises. In: Swingland IR, Klemens MW (Eds) The conservation biology of tortoises. Occasional Papers of the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC), Gland, 24–28.

- Porter D (1815) Journal of a cruise made to the Pacific Ocean, by Captain David Porter. Bradford and Inskeep, Philadelphia, 169 pp.

- Cayot LJ, Gibbs JP, Tapia W, Caccone A (2016) Chelonoidis darwini. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- MacFarland CG, Villa J, Toro B (1974) The Galápagos giant tortoises (Geochelone elephantopus). Part II: Conservation methods. Biological Conservation 6: 198–212.

- Oxford P, Watkins G (2009) Galapagos: both sides of the coin. Imagine Publishing, Morgansville, 256 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Van Denburgh J (1907) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. I. Preliminary descriptions of four new races of gigantic land tortoises from the Galápagos Islands. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 1–6.

- Chancellor G, van Wyhe J (2009) Charles Darwin's notebooks from the voyage of the Beagle. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 656 pp.