Eyelash Palm-Pitviper |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothriechis schlegelii

English common names: Eyelash Palm-Pitviper, Eyelash Viper.

Spanish common names: Cabeza de candado, pestañuda, víbora de pestañas, zampiña, shililí, campanita, sura, papagayo, guacamaya, colgadora, bocaracá, oropel.

Recognition: ♂♂ 68.7 cm ♀♀ 97.9 cm. The Eyelash Palm-Pitviper (Bothriechis schlegelii) may be recognized by its triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits in the loreal region, prehensile (capable of grasping) tail, and enlarged horn-like scales above the eyes, which resemble eyelashes.1,2 Bothriechis schlegelii is a polychromatic snake species,3–5 meaning there is an extraordinary variation in color pattern among individuals. In Ecuador, the most common color morphs are “mossy green” and “Christmas” (green with reddish blotches), but other morphs (golden yellow, grayish white, pink, and purple) have also been recorded.

Picture: Adult from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from FCAT Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Mashpi Reserve, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Bilsa Biological Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Buenaventura Reserve, El Oro, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Cerro Gaital, Coclé, Panamá | |

| |

Picture: Adult from FCAT Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from FCAT Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from FCAT Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Tundaloma Lodge, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Juvenile from Tundaloma Lodge, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Generally common, but uncommon in cloudforest areas in Ecuador.6 Bothriechis schlegelii is an arboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen to semideciduous lowland and montane forests, cloud forests, plantations (cacao, coffee, and banana), pastures with scattered trees, and rural gardens.1,2,7,8 Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers are mostly active at night or at dusk,1,8 especially after a warm, rainy day.6 Most of the time, they forage or perch on arboreal vegetation 20 cm to 35 m above the ground,1,9 although occasionally they move at ground level.10,11 Some snakes reside in the same perch for up to 14 days.8 70.2% of individuals relocate each night, and only 6.4% remain at the same daytime perch site for more than two days.8 During the day, most (85.8%) individuals remain in hunting posture on or close to their night perches,12 but others hide inside bromeliads,9 or occasionally remain active and move at ground level or on vegetation.6,10

Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers are primarily ambush predators, but they also actively forage in search for food.8 As juveniles, their diet includes mostly frogs, which they attract by means of moving their bright yellow tails as a lure.13 Adults feed on frogs (Craugastor longirostris, Pristimantis achatinus, P. walkeri, Smilisca phaeota, Trachycephalus jordani),2,6,14 lizards (anoles, whiptails, and geckos such as Thecadactylus rapicauda),8,15 fish,2 birds (including hummingbirds),14,16 and mammals (bats,4,14 mice,14 and mouse opossums15). Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism,16 but may readily bite if attacked or harassed. Members of this species are preyed upon by other snakes (such as Clelia clelia)17 and by hawks.18,19

Bothriechis schlegelii is a venomous snake (LD50 2–9.2 mg/kg)20–22 that injects an average of ~0.5 cc of venom per bite.16 Its venom is hemotoxic, and, in humans, causes intense pain, swelling, bleeding, defibrination (depletion of the blood’s coagulation factors), hematoma, necrosis (death of cells), and even death.20,22–26 Critically envenomated victims presumably die from intracranial hemorrhage or from acute renal failure.27,28 However, most bites to humans involve only mild to moderate symptoms,29,30 and in some cases, no envenomation at all (“dry bites”).2 Although is not as toxic as other vipers in Ecuador, B. schlegelii is still one of the most dangerous for its arboreal lifestyle, which causes human victims to be bitten on the face, upper body, and hands.24,25,31 In coastal Ecuador, 0.2–10.3% of snakebites are attributed to this species.2,32 Fortunately, the antivenom available in Ecuador neutralizes the venom of B. schlegelii.33 However, the venom’s properties differ drastically between populations and across age categories.22,23 The composition of the venom changes as juveniles transition from having a diet specialized on ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) prey to adults feeding mostly on endothermic (“warm-blooded”) animals.

In some parts of its range, breeding in Bothriechis schlegelii coincides with the rainy season.11 Females become sexually mature at an age of less than three years.34 Copulations last for up to 3 hours and females are capable of storing sperm for up to ~35 months (slightly under three years).13 After a gestation period of 150–166 days (~5 months),13,35 females “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 4–37 (5–9 in Ecuadorian populations) young that are 16–22.5 cm in total length.2,11,36 Females can produce more than one litter per year.34 In captivity, individuals can live up to 20 years.5

Conservation: Least Concern.37 Bothriechis schlegelii is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, frequently encountered in some parts of its range, tolerates moderate forest degradation, and is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.37 In a rainforest locality in Panamá, the occurrence rates of B. schlegelii have actually increased by a factor of ten in the period from 2006 to 2012.38 In another locality in Panamá, the species is extremely common in forest islands within a matrix of pastures.12 However, it is unsure whether such “forest islands” will sustain the species without the presence of a dense population nearby that may act as a source of individuals that can immigrate to the fragmented habitat.12 In addition to extensive habitat loss, Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers also face the threat direct killing,6 traffic mortality,39 and poaching. Bothriechis schlegelii is one of the most frequent targets of the illegal trade of wildlife.1,40

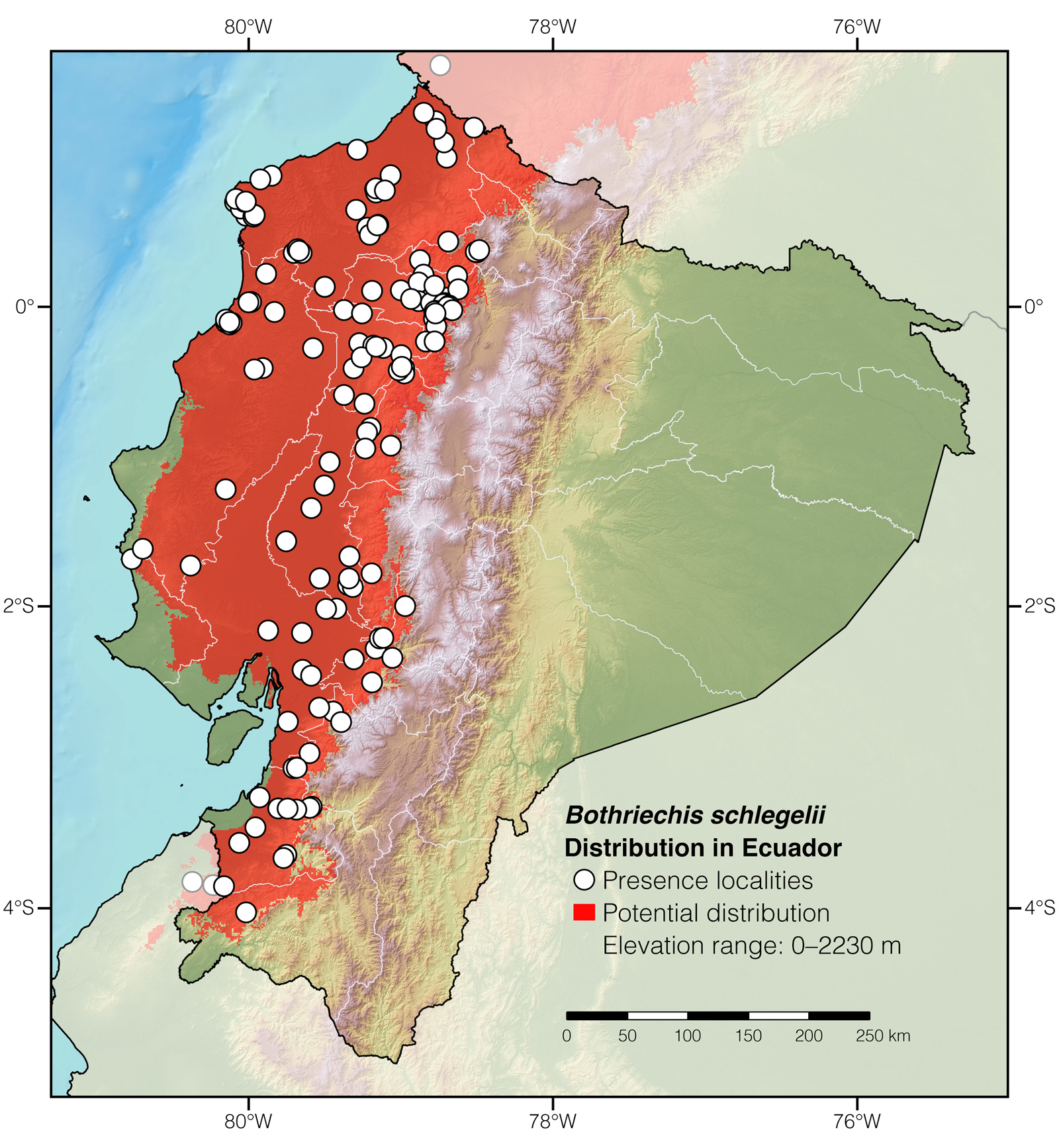

Distribution: Bothriechis schlegelii is native to the Neotropical lowlands and adjacent mountainous slopes from southeastern Mexico to northwestern Perú.

Etymology: The generic name Bothriechis, which is derived from the Greek words bothros (meaning “pit”) and echis (meaning “viper”),41 refers to the heat-sensing loreal pits. The specific epithet schlegelii honors Hermann Schlegel (1804–1884), a renowned German ornithologist and herpetologist.1

See it in the wild: Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers can be seen with ~1–30% certainty at night, especially during the rainy season (December to May), in forested areas throughout western Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find Eyelash Palm-Pitvipers in the wild in Ecuador are: Bilsa Biological Reserve, Buenaventura Biological Reserve, Canandé Reserve, and Jama-Coaque Ecological Reserve. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

FAQ

Are Eyelash Vipers deadly? Yes, some bites may result in death of the victim.20,22–26 However, the majority of victims recover with the use of antivenom.32,33

Can an Eyelash Viper kill a human? Yes, Eyelash Vipers can cause human fatalities.20,22–26 However, the majority of victims recover with the use of antivenom.32,33

Do Eyelash Vipers eat hummingbirds? Yes, there are confirmed reports of Eyelash Vipers capturing and eating hummingbirds.14

How fast can an Eyelash Palm-Pitviper kill you? The fastest recorded death following a bite of an Eyelash Palm-Piviper is women that died within 2–3 hours after being bitten in the tongue.25

What eats an Eyelash Viper? Eyelash Palm-Piviper are preyed upon by snakes (such as Clelia clelia)17 and by hawks.18,19

Special thanks to Thibaud Aronson and Cheryl Vogt for symbolically adopting the Eyelash Palm-Pitviper and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. Frank Pichardo,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di Doménico.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Bothriechis schlegelii. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Werman SD (1984) Bothrops schlegelii (eyelash viper). Coloration. Herpetological Review 15: 17–18.

- Barrio-Amorós C (2015) Bothriechis schlegelii. Predation and color pattern. Mesoamerican Herpetology 2: 117–119.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Duke JA (1967) Herpetological dietary: bioenvironmental and radiological-safety feasibility studies, Atlantic–Pacific interoceanic canal. Battelle Memorial Institute, Columbus, 35 pp.

- Sorrell GG (2009) Diel movement and predation activity patterns of the Eyelash Palm-Pitviper, Bothriechis schlegelii. Copeia 2009: 105–109.

- Leenders T (2019) Reptiles of Costa Rica: a field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 625 pp.

- Rojas-Morales JA (2012) Snakes of an urban-rural landscape in the central Andes of Colombia: species composition, distribution, and natural history. Phyllomedusa 11: 135–154.

- Solórzano A (2004) Serpientes de Costa Rica. Distribución, taxonomía e historia natural. Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, 792 pp.

- Sorrell GG (2007) Natural history and conservation of the Eyelash Palm-Pitviper (Bothriechis schlegelii) in Western Panamá. MSc thesis, Auburn University, 54 pp.

- Antonio FB (1980) Mating behavior and reproduction of the eyelash viper (Bothriechis schlegelii) in captivity. Herpetologica 36: 231–233.

- Meza-Ramos PM, Almendáriz AL, Yánez-Muñoz MH (2019) Datos sobre la dieta de Bothriechis schlegelii (Berthold, 1846) (Serpentes-Viperidae) en el occidente del Ecuador. Boletín Técnico 6: 15–18.

- Lindey SD, Sorrell GG (2004) Bothriechis schlegelii: predator/prey mass ratio, and diet. Herpetological Review 35: 272–273.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Chavarría M, Barrio-Amorós C (2014) Clelia clelia. Predation. Mesoamerican Herpetology 1: 286.

- Laurencio D (2005) Bothriechis schlegelii (Eyelash Palm Pit-viper, Bocaracá). Attempted predation. Herpetological Review 36: 188.

- Gerhardt RP, Harris PM, Vásquez MA (1993) Food habits of nesting great black hawks in Tikal National Park, Guatemala. Biotropica 25: 349–352.

- Lomonte B, Escolano J, Fernández J, Sanz L, Angulo Y, Gutiérrez JM, Calvete JJ (2008) Snake venomics and antivenomics of the arboreal Neotropical pitvipers Bothriechis lateralis and Bothriechis schlegelii. Journal of Proteome Research 7: 2445–2457.

- Prezotto-Neto JP, Kimura LF, Alves AF, Gutiérrez JM, Otero R, Suárez AM, Santoro ML, Barbaro KC (2016) Biochemical and biological characterization of Bothriechis schlegelii snake venoms from Colombia and Costa Rica. Experimental Biology and Medicine 241: 2075–2085.

- Kuch U, Mebs D, Gutiérrez JM, Freire A (1996) Biochemical and biological characterization of the Ecuadorian pitvipers (genera Bothriechis, Bothriopsis, Bothrops, and Lachesis). Toxicon 34: 714–717.

- Pla D, Sanz L, Sasa M, Acevedo ME, Dwyer Q, Durban J, Pérez A, Rodriguez Y, Lomonte B, Calvete JJ (2017) Proteomic analysis of venom variability and ontogeny across the arboreal palm-pitvipers (genus Bothriechis). Journal of Proteomics 152: 1–12.

- Ditmars RL (1930) The poisonous serpentes of the New World. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 33: 78–132.

- Ayerbe S, Paredes A, Gávez DA (1979) Estudio retrospectivo sobre ofidiotoxicosis en el departamento del Cauca. 2da parte. Aspectos clínicos, epidemiológicos y complicaciones. Cuadernos de Medicina, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad del Cauca 4: 33–45.

- Lieske H (1963) Symptomatik und Therapie von Giftschlangenbissen. In: von Behring E (Ed) Die Giftschlangen der Erde. N.G. Elwert Universitäts und Verlagsbuchhandlung, Marburg, 121–160.

- Mekbel ST, Céspedes R (1963) Las lesiones renales en el ofidismo. Acta Médica Costarricense 6: 111–118.

- Bolaños RA (1984) Serpientes, venenos, y ofidismo en Centroamérica. Editorial Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, 136 pp.

- Ayerbe S (1990) Bothropic envenomation in Colombia: changes in hematological tests. Journal of Toxicology 9: 103–131.

- Otero R, Gutiérrez J, Mesa MB, Duque E, Rodrı́guez O, Arango JL, Gómez F, Toro A, Cano F, Rodrı́guez LM, Caro E, Martı́nez J, Cornejo W, Gómez LM, Uribe FL, Cárdenas S, Núñez V, Dı́az A (2002) Complications of Bothrops, Porthidium, and Bothriechis snakebites in Colombia. A clinical and epidemiological study of 39 cases attended in a university hospital. Toxicon 40: 1107–1114.

- Álvarez del Toro M (1983) Los reptiles de Chiapas. Instituto de Historia Natural, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, 248 pp.

- Betancourt RM (2012) Incidencia, zonas de riesgo y prevención de accidentes ofídicos en áreas rurales de las provincias de Manabí y Los Ríos, Ecuador, años 2007 a 2009. BSc thesis, Universidad Central de Ecuador, 165 pp.

- Galofre-Ruiz M (2016) Emponzoñamiento causado por mordedura de la serpiente Bothriechis schlegelii. Reporte de dos casos ocurridos en Colombia. Case Reports 3: 1–8.

- Blody DA (1983) Notes on the reproductive biology of the Eyelash Viper Bothrops schlegelii in captivity. Herpetological Review 14: 45–46.

- Gómez A, Chacón D, Rodríguez S, Corrales G (2015) Reproduction and sperm storage in a captive female Bothriechis schlegelii (Serpentes: Viperidae) in Costa Rica. Mesoamerican Herpetology 2: 581–584.

- Murphy JB, Mitchell LA (1984) Miscellaneous notes on the reproductive biology of reptiles. Thirteen varieties of the genus Bothrops (Serpentes, Crotalidae). Acta Zoologica et Pathologica Antverpiensia 78: 199–214.

- Chaves G, Lamar W, Porras LW, Solórzano A, Sunyer J, Rivas G, Caicedo JR, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P (2019) Bothriechis schlegelii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Zipkin EF, DiRenzo GD, Ray JM, Rossman S, Lips KR (2020) Tropical snake diversity collapses after widespread amphibian loss. Science 367: 814–816.

- Quintero-Ángel A, Osorio-Dominguez D, Vargas-Salinas F, Saavedra-Rodríguez CA (2012) Roadkill rate of snakes in a disturbed landscape of Central Andes of Colombia. Herpetology Notes 5: 99–105.

- Rojas P (2020) Con las “manos en la maza”: sorprendidos estadounidenses que se llevaban bocaracá de parque nacional. CRHoy Noticias. Available from: www.crhoy.com

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.