Published April 15, 2022. Open access. | Gallery ❯ |

High-Andean Anole (Anolis heterodermus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Anolidae | Anolis heterodermus

English common names: High-Andean Anole, Flat Andes Anole, Giant Andes Anole.

Spanish common names: Anolis altoandino, anolis andino plano, camaleón andino, camaleón de páramo.

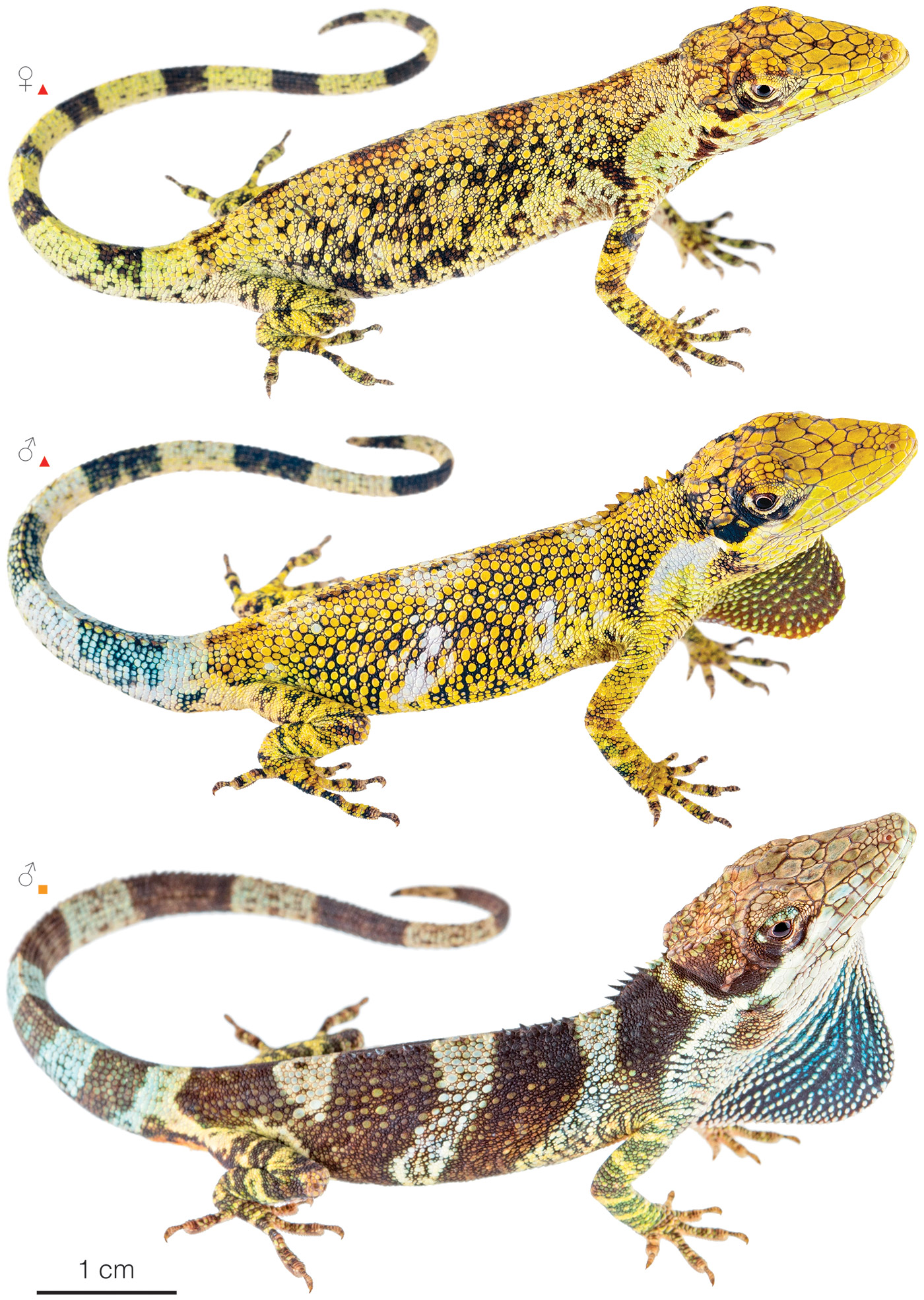

Recognition: ♂♂ 18.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.3 cm. ♀♀ 19.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.6 cm..1 Anoles are easily distinguishable from other lizards by their diurnal habits, extensible dewlap in males, expanded digital pads, and granular scales on the dorsum and belly.2,3 The High-Andean Anole (Anolis heterodermus) belongs to the phenacosaur group of anoles, which are characterized by having large smooth headscales, short limbs, short and prehensile tail, and chameleon-like movements.4–6 This species differs from other members of the group mainly on the basis of coloration.1,7 The dorsum is usually bright green and sometimes grayish; the ventral surfaces are yellowish green. Under stress, the coloration can change to dark green.8,9 Females may have a broad black to pale brown mid-dorsal stripe. The dewlap in males of A. heterodermus from Ecuador is dark brown with lemon green scales whereas males from Colombia have a dark blue dewlap with whitish scales (Fig. 1).The tail has seven dark brown transverse bands alternating with light blue (proximally) and light brown (distally) bands.1,10 Anolis vanzolinii and A. orcesi differ from A. heterodermus in dewlap coloration.4,5 The dewlap of A. vanzolinii is pale blue in the center and orange-yellow on the periphery, with rows of white granules.9 The dewlap of A. orcesi is uniformly orange, yellow, or lime green.9

Figure 1: Individuals of Anolis heterodermus from Chilma Bajo, Carchi province, Ecuador (); and Supatá, Cundinamarca department, Colombia ().

Natural history: CommonRecorded weekly in densities above five individuals per locality.. Anolis heterodermus inhabits high elevation ecosystems where other anoles are not known to occur.8 This includes old-growth to moderately disturbed high elevation evergreen forests, forest edges, and semi-open areas such as shrubby paramos and pastures with living fences.8–11 Anolis heterodermus is included in the “twig” anole guild because it has a comparatively small SVL (~8 cm snout-vent-length), a short prehensile tail (≤1.5 SVL), and very short legs (0.5 SVL).11,12 Flat Andes Anoles use the undergrowth and herbaceous forest strata at 0.3–4 m above the ground.1,9,11 They exhibit high site fidelity, being found within a 3 m radius for several months.13 These lizards are diurnal, exhibit active thermoregulation,14 and are basking and foraging when the ambient temperature is 15.5–22.5 °C.13 They forage primarily on two types of perches: tree trunks (~14% of the time) and small twigs and branches less than 2 cm in diameter (~75% of the time),8 although individuals have also been spotted on the ground or on barbed wires.8 At night, these anoles sleep with their head up on vines and twigs at 2.5–5 m above ground.1

Communication between individuals of Anolis heterodermus involves head bobs, flashing of the dewlap, sagittal body expansion, and pushup displays.15,16 High-Andean Anoles are foragers rather than sit-and-wait predators6,17 and their diet is insectivorous.18 In captivity, Flat Andes Anoles have been fed with flies, mosquitoes, crickets, and mealworms.16,18 Anti-predatory strategies include camouflage, moving to the other side of the branch, dropping off the perch, fleeing in dense vegetation, and shedding the tail.8,18 Anecdotal information suggests that these lizards are preyed upon by birds of prey and thrushes.18 Females, which reach sexual maturity at a snout-vent-length of 5.5 cm,8 lay clutches of a single egg.6,19 In the cold paramo climate, the incubation period for the single egg is about one year,6,18 longer than that of any other known squamate reptile.20

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..21 Anolis heterodermus is listed in this category given its wide distribution, presence in protected areas, presumed large and stable populations,8 and adaptability to human-modified environments.13 However, fragmentation and loss of natural vegetation in high elevation ecosystems can negatively impact the reproductive dynamics of some populations.13 Furthermore, degradation of the Andean landscape can result in smaller patch sizes, thus slowing demographic trends and making populations more vulnerable to anthropogenic disturbances or natural stochastic events within a short time period.13 Lastly, there is published evidence that suggests that A. heterodermus is a species complex22 rather than a single widely distributed species; thus, some populations might qualify for a different threat category.

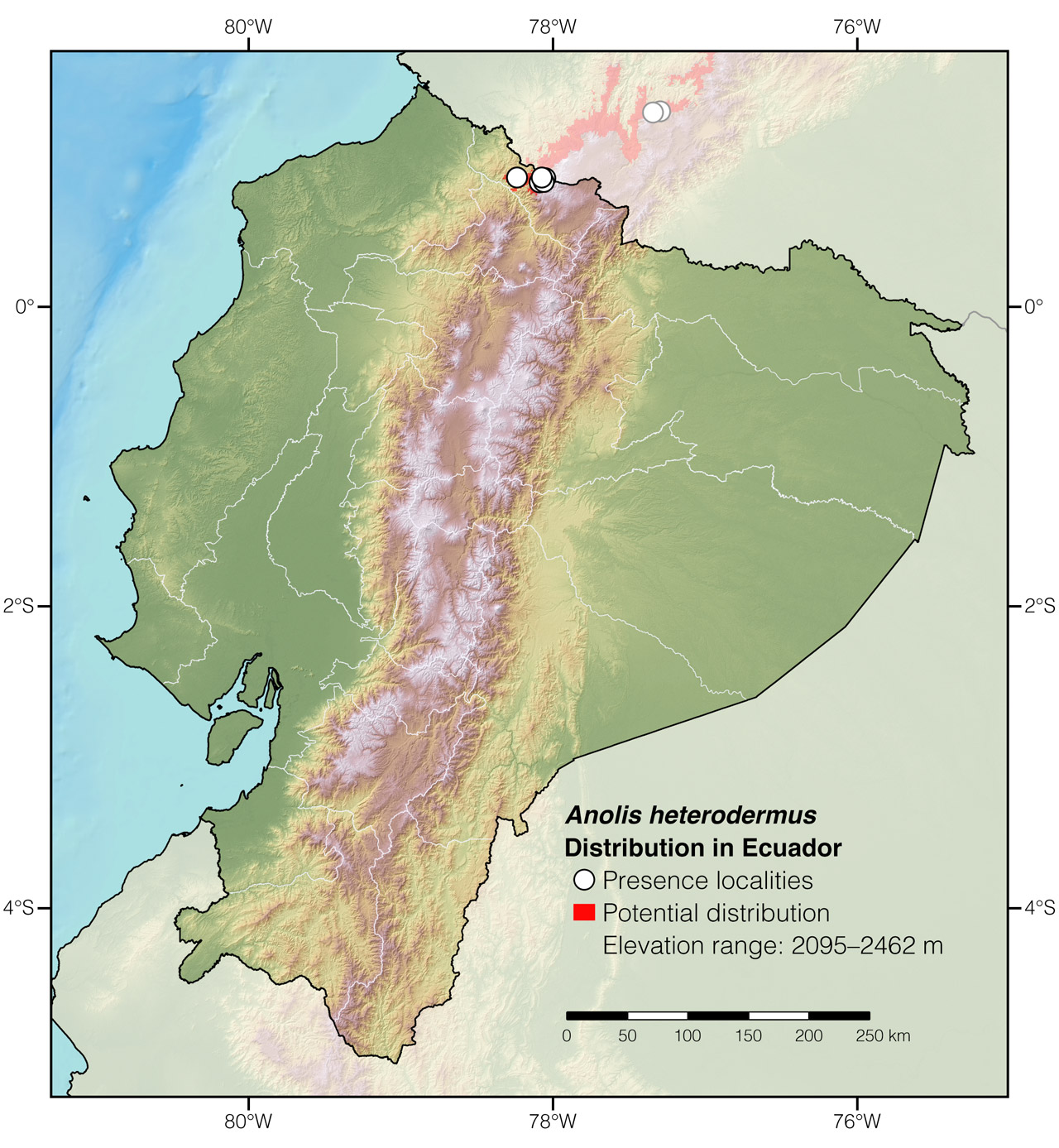

Distribution: Anolis heterodermus is widely distributed throughout the three cordilleras in the Colombian Andes as well as in the extreme northwestern slopes of the Andes in Ecuador. In the latter country, the species has been recorded at elevations between 2095 and 2462 m, but in Colombia the species reaches 3750 m in elevation (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Anolis heterodermus in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Anolis is thought to have originated from Cariban languages, specifically from the word anoli, which is the name Arawak peoples may have used to refer to this group of lizards.23 The specific epithet heterodermus, which comes from the Green words heteros (meaning “different”) and derma (meaning “skin”),24 probably refers to the skin on the dorsum, which is covered in small granules with interspersed broad scales.6

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Flat Andes Anoles are easy to find in the immediate surroundings of the town Chilma Bajo. These lizards can be spotted almost every night by scanning low shrubs along dirt roads. They are usually seen roosting on small twigs and branches.

Special thanks to Davis Blair for symbolically adopting the High-Andean Anole and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Angie Tovar-OrtizaAffiliation: Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Biodiversity Field Lab, Khamai Foundation, Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Tovar-Ortiz A, Arteaga A (2022) High-Andean Anole (Anolis heterodermus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Guayasamin JM (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/JMSI4908

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal O, Ayala F, Carvajal-Campos A (2010) Reptilia, Squamata, Iguanidae, Anolis heterodermus Duméril, 1851: distribution extension, first record for Ecuador and notes on color variation. Check List 6: 189–190. DOI: 10.15560/6.1.189

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Castañeda MR, de Queiroz K (2013) Phylogeny of the Dactyloa clade of Anolis lizards: new insights from combining morphological and molecular data. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 160: 345–398. DOI: 10.3099/0027-4100-160.7.345

- Lazell JD (1969) The genus Phenacosaurus (Sauria, Iguanidae). Breviora 325: 1–24.

- Williams EE, Orcés GV, Matheus JA, Bleiweiss R (1996) A new giant phenacosaur from Ecuador. Breviora 505: 1–32.

- Dunn ER (1944) The lizard genus Phenacosaurus. Caldasia 3: 57–62.

- Williams EE, Rand H, Rand AS, O’Hara RJ (1995) A computer approach to the comparision and identification of species in difficult taxonomic groups. Breviora 502: 1–47.

- Miyata KI (1983) Notes on Phenacosaurus heterodermus in the Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia. Journal of Herpetology 17: 102–105. DOI: 10.2307/1563796

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Duméril AMC, Duméril AHA (1851) Catalogue méthodique de la collection des reptiles. Muséum National d’Histoire Haturelle, Paris, 224 pp.

- Moreno-Arias R, Velasco JA, Urbina Cardona J, Cárdenas-Arévalo G, Medina Rangel G, Gutiérrez Cárdenas P, Olaya-Rodriguez M, Noguera-Urbano E (2021) Atlas de la biodiversidad de Colombia. Anolis. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 72 pp.

- Nicholson KE, Crother BI, Guyer C, Savage JM (2012) It is time for a new classification of anoles (Squamata: Dactyloidae). Zootaxa 3477: 1–108. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3477.1.1

- Moreno-Arias RA, Urbina-Cardona JN (2012) Population dynamics of the Andean lizard Anolis heterodermus: fast-slow demographic strategies in fragmented scrubland landscapes. Biotropica 45: 253–261. DOI: 10.1111/j.1744-7429.2012.00903.x

- Mendez-Galeano MA, Paternina-Cruz RF, Calderón-Espinosa ML (2020) The highest kingdom of Anolis: thermal biology of the Andean lizard Anolis heterodermus (Squamata: Dactyloidae) over an elevational gradient in the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia. Journal of Thermal Biology 107: e2017018. DOI: 10.1590/1678-4766e2017018

- Jenssen TA (1975) Display repertoire of a male Phenacosaurus heterodermus (Sauria: Iguanidae). Herpetologica 31: 48–55.

- Beltrán I, Barragán-Contreras LA (2019) Male courtship display in two populations of Anolis heterodermus (Squamata: Dactyloidae) from the Eastern Cordillera of Colombia. Herpetology Notes 12: 881–884.

- Kästle W (1965) Zur Ethologie des Andes-Anolis (Phenacosaurus richteri). Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 22: 751–769.

- Osorno-Mesa H, Osorno-Mesa E (1946) Anotaciones sobre lagartos del género Phenacosaurus. Caldasia 17: 123–130.

- Blackburn D (1999) Viviparity and oviparity: evolution and reproductive strategies. In: Knobil E, Neill JD (Eds) Encyclopedia of Reproduction. Academic Press, London, 994–1003.

- Fitch H (1970) Reproductive cycles in lizards and snakes. Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 247 pp.

- Castañeda MR, Ines Hladki A, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N (2020) Anolis heterodermus. The IUCN red list of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T44577387A44577394.en

- Vargas-Ramírez M, Moreno-Arias R (2014) Unknown evolutionary lineages and population differentiation in Anolis heterodermus (Squamata: Dactyloidae) from the Eastern and Central Cordilleras of Colombia revealed by DNA sequence data. South American Journal of Herpetology 9: 131–141. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-13-00013.1

- Allsopp R (1996) Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 776 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Anolis heterodermus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Finca San Isidro | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Cauca | La Vega | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Cauca | Santo Domingo | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Cauca | Usenda | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Nariño | Reserva Natural Morar | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Pasto | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Alto Gualpi | DHMECN 13216 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Cañón de El Morán | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chilma Bajo | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Maldonado, 18 km SE of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Near Tres Marias waterfall | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2010 |